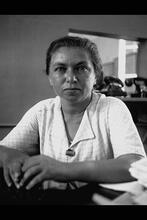

Esther Kreitman

Esther Kreitman was the only female writer in one of the most prominent families in Yiddish literature. Born in Poland in 1891, Kreitman learned several languages and became interested in world literature despite her parents’ refusal to provide her with a formal education. After the disintegration of her marriage in 1926, Kreitman moved to England and supported herself through her writing, traveling, and speaking. Though her literary work has often been overshadowed by the work of her brothers I.B. and I.J. Singer, Kreitman produced notable contributions to the genre of Yiddish Literature in her novels and short stories. Her most famous novel, Der Sheydim Tants, brilliantly draws on her experiences growing up in a hasidic family and the turmoil of pre-World War I Poland.

As the only female writer in what many consider the most singular family in the history of Yiddish literature, Esther Kreitman and her small literary output have been overshadowed by the voluminous works of her brothers I.J. and I.B. Singer. Her notable contribution to Yiddish literature, unheralded in her lifetime, was to write in Yiddish in support of the Jewish Enlightenment; European movement during the 1770shaskalah (Jewish enlightenment) from a female perspective, an achievement made all the more remarkable by her lifelong struggle with depression and perhaps other undiagnosed emotional and physical illnesses which disrupted her ability to write. Her ruthless depictions of women’s place in hasidic society remain as painful as fresh wounds. In her autobiographical novel Der Sheydim Tants (Deborah) she wrote:

“In his heart of hearts, Reb Avram Ber disapproved of his wife’s erudition. He thought it wrong for a woman to know too much, and was determined that this mistake should not be repeated in Deborah’s case. Now there was in the house a copy of Naimonovitch’s Russian Grammar, which Deborah always studied in her spare moments, but whenever her father caught her at this mischief he would hide the book away on top of the tiled stove out of her reach, and then she would have to risk her very life to recover it.”

Early Life and Family

Kreitman was born Hinde Esther Singer on March 31, 1891 in Bilgoraj, Poland. Though her rabbi father, Pinkhes Mendl Singer, and educated mother, Batsheva Zylberman Singer, daughter of the rabbi of Bilgoraj, refused to provide her with the formal education that she strongly desired, she nevertheless learned to read several languages and became interested in world literature. In her youth she wrote stories, which she never intended for publication and eventually destroyed, well before her younger brothers had taken up their pens. Her parents were both abusive and neglectful of her, in marked contrast to their treatment of her brothers, Israel Joshua (1893–1944), Isaac Bashevis (1904–1991) and Moshe (1906–c. 1944). She escaped this traumatic situation into an arranged marriage (c. 1912) with an Antwerp diamond cutter, Avraham Kreitman, which proved unhappy.

After the disintegration of her marriage in 1926 Kreitman divided her time between Warsaw and London, eventually settling permanently in England and struggling to support herself by writing, translating and speaking. Kreitman’s stories and serialized novels appeared in many Yiddish newspapers world-wide before being published in book form. Three books were published in Yiddish in her lifetime: the novels Der Sheydim Tants (The Devil’s Dance, 1936) and Brilyantn (Diamonds, 1944), and the collection of stories, Yikhes (Lineage, 1949). Der Sheydim Tants was published in English under the title Deborah in 1946. In both languages her work received favorable notices. In addition to writing her own fiction, Kreitman translated Dickens and Shaw into Yiddish and was active not only in maintaining the London literary journal Loshn un Lebn, but also in socialist circles. She died on June 13, 1954, in her apartment in London, and was cremated according to her wishes.

Of her brothers, I.B. Singer (known as Bashevis in Yiddish) moved to New York and became the Yiddish writer best known to non-Yiddish readers, garnering a multitude of translations and a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978. Also in New York I.J. Singer, though less frequently translated, was highly regarded in Yiddish literary circles. Bashevis praised his brother’s novels strongly and frequently after his death in 1944 but usually failed to mention the writings of his still-living sister. In his own writings he referred to her by the name Hinde, further obscuring her identity. Bashevis’s story “Yentl the Yeshiva Boy” is said to have been based, in part, on his sister’s thwarted desire for education: feminist critics see it as a literary appropriation curiously devoid of empathy, especially given Bashevis’s lack of real-life aid to Kreitman’s literary or personal ambitions. The youngest brother, Moshe, who was not a writer, became a rabbi, remained in Poland, and perished in the Holocaust. Kreitman’s son, Morris Kreitman (May 11, 1913–March 16, 2003), wrote stories and translated his mother’s work (using his own name as well as the pseudonym Martin Lea). He went on to a long career in journalism in Palestine and later Israel, using the name Maurice Carr, by which he is generally known in Israel today.

Literary Career

Kreitman’s masterwork is undoubtedly Der Sheydim Tants, which draws on her experiences growing up in a hasidic family amid the social and political turmoil of pre-World War I Poland. Her depiction of the impoverished rabbi’s family, in which the father is a fool and the mother a cold and embittered scholar, paints a different picture of the Singer family than that found in her brothers’ writings (though the latter did note the mismatch between their parents). In the words of literary critic Anita Norich, “Kreitman shares little of her brothers’ nostalgic search for the true past” (Norich, 1990). Indeed, Kreitman’s view of tradition could be said to be unflinchingly critical in the face of male sentimentality. Der Sheydim Tants, which is striking for its continually bleak view of the possibilities and limits of human relationships, ends on a note of complete despair. Throughout the novel’s narrative, relations both between men and women and among women are tainted as insincere, exploitative, and competitive. This quality is not found in her short stories, which include many positive and hopeful endings, and many characters who are able to comfort and support each other and to transform themselves. Interestingly, several of her stories have seen more than one translation, although the majority remain available in Yiddish only. Her second novel, Brilyantn, which has never been translated, was praised by Melech Ravitch (1893–1976) and others for its wealth of detail and insider knowledge of the Jewish diamond trade.

Selected Works

English

Deborah (English translation of Der Sheydi cm Tants). Trans. by Maurice Carr. London: W. and G. Foyle, 1954. Reprint. London: Virago, 1983, introduction by Clive Sinclair. Reprint. Helen Rose Scheuer Jewish Women’s Series. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2004.

“The New World” (English translation of Di Naye Velt). Trans. by Joshua A. Fogel. Yale Review 73 (Summer 1984): 525–532.

“The New World” (English translation of Di Naye Velt). Trans. by Barbara Harshav. Lilith 16, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 10–12. Reprinted in Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers. Edited by Frieda Forman, Ethel Raicus, Sarah Silberstein Swartz and Margie Wolfe. Introduction by Irena Klepfisz. Toronto: Second Story Press, 1994.

“The Relic” (English translation of Atlasene Kapote). Trans. by Morris Kreitman [Maurice Carr]. In Jewish Short Stories of Today. Edited by Morris Kreitman. London: Faber & Faber, 1938.

“The Satin Coat” (English translation of Atlasene Kapote). Trans. by Ellen Cassedy. In Beautiful as the Moon, Radiant as the Stars, edited by Sandra Bark. New York: Time Warner Publishing, 2003.

Yiddish

Der Sheydim Tants. Warsaw: Brzoza, 1936.

Brilyantn. London: W. and G. Foyle, 1944.

Yikhes. London: Narod Press, 1949.

Uncollected stories appear in Loshn un Lebn. London: 1946–1955.

Other Languages

La Danse des Demons (French translation of Der Sheydim Tants). Trans. by Carole Ksiazenicer and Louisette Kahane-Dajezer. Paris: Des Femmes, 1988.

Deborah: Narren Tanzen im Ghetto (German translation of Der Sheydim Tants). Trans. By Abraham Teuter. Frankfurt: Alibaba, 1985.e

“El Nuevo Mundo” (Spanish translation of Di Naye Velt). Trans. by Alicia Ramos Gonzales and J. Abad. Raices 44 (otoño 2000): 37–39.

English

Biographical entry in Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers. Edited by Frieda Forman, Ethel Raicus, Sarah Silberstein Swartz and Margie Wolfe, Introduction by Irena Klepfisz, 357–359. Toronto: Second Story Press, 1994.

Biographical note in Deborah. London: St. Martin’s Press, 1983.

Cambridge Biographical Encyclopedia, 2nd edition (1998), s.v. “Kreitman, Esther.”

Fogel, Joshua A. Introduction to “The New World,” by Esther Kreitman. Yale Review 73 (Summer 1984): 525–526.

Goldman, Ari L. “The long neglected sister of the Singer family.” New York Times, April 4, 1991: C15.

Homberger, Eric. “Charles Reznikoff’s Family Chronicle: Saying thank you and I’m sorry.” In Charles Reznikoff, Man and Poet, edited by Milton Hindus, 327–342. Orono, Maine: National Poetry Fondation, 1984.

Jones, Faith. “Esther Kreitman: Renewed recognition of her work.” Canadian Jewish Outlook 38, no. 2 (Mar/Apr 2000): 17–18.

Norich, Anita. The Homeless Imagination in the Fiction of Israel Joshua Singer. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Norich, Anita. “The family Singer and the autobiographical imagination.” Prooftexts 10, no. 1 (Jan. 1990): 97–107.

Pitock, Todd. “Forgotten Singer, forgotten song: Hinde Esther Singer Kreitman.” Jewish Affairs Winter 1993: 127–133.

Prager, Leonard. “Esther Kreitman.” Yiddish Culture in Britain, 382-388. Frankfurt: P. Lang, 1990.

Prawer, S.S. “The first family of Yiddish.” Times Literary Supplement 4178 (April 29, 1983): 419–420.

Sinclair, Clive. Introduction to Deborah, by Esther Kreitman. Trans. By Maurice Carr. London: Virago, 1983.

Sinclair, Clive. “Esther, the silenced Singer.” Los Angeles Times, Sunday, April 14, 1991: BR1, 11.

Sinclair, Clive. “Esther Singer Kreitman: the trammeled talent of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s neglected sister.” Lilith, Spring 1991: 8–9.

Singer, Isaac Bashevis. “My sister.” In In My Father’s Court, 151-155. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1975.

Wisse, Ruth R. The Modern Jewish Canon: a Journey Through Language and Culture. New York: Simon and Shuster, 2000.

Yiddish

Biographical entry in Leksikon fun der Nayer Yidisher Literatur. New York: 1981, v. col. 260–261.

Botoshanski, Yankev. “Tsvishn yo un neyn: Ester Kreytman o’h.” Di Prese August 20, 1954: 4.

Carr, Maurice. “Kadish mayn muter Ester Kreytman.” Loshn un Lebn 173 (June 1954): 8–10.

Handler, Troim Katz. “Di shvester: Hinde-Ester Zinger-Kreytman.” Yidishe Kultur 59, no. 5–6 (May–June 1997): 47–49.

Lev, Yosef Hilel. “Shtrikhn tsu Ester Kreytmans literarishe portret.” Loshn un Lebn 118 (November 1949): 27–31.

Ravitch, Melech. “Ester Kraytman.” Mayn Leksikon, vol. 4 pt. 2. Montreal: 1982, 254–256.

Singer, I.B. [pseud. Yitskhak Varshavski]. “In mayn foter’s bes-din shtub.” Serialized in Forverts: see May 5, 1955, p. 2. [Later collected in In Mayn Foter’s Bez-Din Shtub, in English translation as In My Father’s Court].

Other Languages

“Esther Kreytman.” Davar 15 Kislev [December 10], 1954: 6.

Gonzales, Alicia Ramos. “Un modelo para Aaron: Esther Kreitman, o la tragedia de la mujer intelectual.” Raices 42 (Primavera 2000): 41–50.

Lewi, Henri. “Demons et dibbouks.” YOD: Revue des Etudes Moderns et Contemporaines Hebraiques et Juives 31–32 (1990): 53–66.