The Jewish Woman

Courtesy of the National Council of Jewish Women.

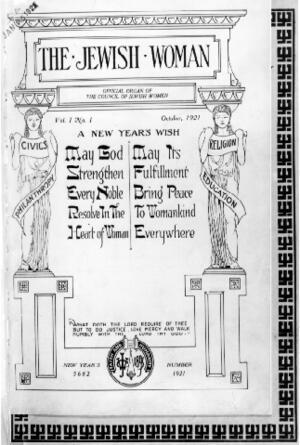

The cover reads as follows:

The Jewish Women

Official Organ of the Council of Jewish Women

Vol. 1 No. 1 October, 1921

A New Year's Wish

May God Strengthen Every Noble Resolve In The Heart of Woman

May Its Fulfillment Bring Peace To Womankind Everywhere

"What Doth The Lord Require Of Thee

But To Do Justice, Love, Mercy and Walk

Humbly With the Lord Thy God."

New Year's 5682 Number 1921

The Jewish Woman quarterly magazine was launched by the National Council of Jewish Women in 1921 to provide information about the Council’s activities and promote the voices of Jewish women. An explicitly feminist publication, the magazine ran for eleven years. Its articles reflected current events, as well as the complicated and often contradictory ideas of the Council. The magazine stopped publishing in October 1931. The Jewish Woman’s legacy was the example it set by continuously aiming to serve as “a platform that would unite all Jewish women in the interests that they share in common.”

Background

The Jewish Woman, a quarterly magazine published under the auspices of the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW) between 1921 and 1931, was created to give the world “its first organized record of Jewish womanhood’s aspirations and successes.” The distinctly Jewish feminist message for which the magazine’s editors strove was evident on the cover of its first issue. It featured a The Jewish New Year, held on the first and second days of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. Referred to alternatively as the "Day of Judgement" and the "Day of Blowing" (of the shofar).Rosh Hashanah message that displayed the NJCW’s motto and seal alongside twin pillars indicating the council’s work in civics, philanthropy, religion, and education. Publication of The Jewish Woman also coincided with the council’s objective of expanding its membership and influencing various social issues of its day.

The Jewish Woman was a precursor to the Council Woman, a magazine that NCJW published in the 1940s and 1950s, and also to its successor, the Council Journal. During its eleven-year history, The Jewish Woman was edited by Estelle Sternberger, a national board member from Cincinnati. A 1926 editorial by Sternberger crystallized the goals of The Jewish Woman: The magazine “was launched to meet a two-fold purpose; first to give the members of the National Council of Jewish Women, and the public, information on all phases of the Council’s work, international, national and local; and secondly to provide a medium that would voice the ideals and aspirations of Jewish womanhood in every field of endeavor.”

Both of these expectations were realized in the magazine’s feature articles, the message from the NCJW president, editorials, book reviews, and reports from the “eighteen fields”: NCJW’s various committees that focused on a variety of subjects including education, religion, and civic life. One such committee, Purity of Press, tracked antisemitism in the media by performing the watchdog role later taken up by groups such as the Anti-Defamation League. However, the first issues of The Jewish Woman were targeted to council members, a cross section of middle-class women. Some of them thought of the council primarily as a social outlet; others wanted their council participation to be more political and civic-minded. It was also directed to the newly arrived immigrant who sought help from the first two groups.

Messaging

A 1922 article on Jewish women in civic life provided insight into this varied audience. The author scolded council members for being too impatient and therefore unable to meet the challenges of civic life. “We [Jews] are not a particularly patient people. We are willing to do things, but want them done quickly. We want to see results. Hence philanthropic work appeals to us keenly, and club work has its prompt and pleasant returns for time expended.”

Another article in 1926 was more prescient in its evaluation by suggesting that women’s lack of political experience might be “counterbalanced by a certain freshness and hopefulness that [they] bring to the adventure of participating in their government and their distinctly feminine point of view as to human values in government.”

The magazine also broadened the focus of the council’s influential and award-winning monthly newsletter, The Immigrant. Early issues reflected NCJW’s self-appointed role as “The Great Interpreter.” The council, renowned for its work with immigrants, spoke out against the harsh immigration laws then recently enacted in Congress. A 1924 editorial entitled “Sane Americanism” decried the “unfortunate tendency [that] has recently appeared among some of our legislators and citizens to challenge this distinctive feature [the melting-pot idea] of America’s history.”

In her April 1922 “President’s Message,” Rose Brenner wrote that when the council “assumed as its chief obligation, the care and protection of the immigrant woman and girl, it became the interpreter of America to the foreign-born Jewess.” To that end a 1925 editorial lauded the opening of a Jewish School of Social Work as filling a great void in American society. NCJW took pride in its social work activity and thought of it as a valuable scientific discipline. The creation of a professional school gave credence to that view.

However, Brenner was unequivocal about NCJW’s goal to “re-interpret the Jew and Judaism back to America…. It is neither just nor fitting that the greater American public should see in the foreign-born its only exemplar of Judaism and the Jew.” Balancing assimilation into American society with Judaic practice was continuously reflected upon and redefined in the magazine. The February 1923 issue highlighted the tension between the social and religious demands of the old and new worlds. “The organization woman realizes that she is a new type in the History of Women, and lives in a new world which her grandmothers did not know—the world of conflicting ideas.”

Many of those contradictory ideas, examined in the pages of The Jewish Woman, were extrapolated from the current events of the day. Women’s equality through suffrage and economic freedom was the subject of a 1922 editorial that cautioned that women “will have to determine whether the proposed ‘freedom’ and ‘rights’ would be to the hurt rather than to the benefit of women.” The recent memory of World War I also inspired pacifism in the NCJW ranks. The Jewish Woman often reported on NCJW resolutions that called for the elimination of war as a means of settling any dispute.

Structural Change

In keeping with the council’s efforts to boost membership as well as the expanding editorial focus of The Jewish Woman, the editors attempted to establish a paid circulation. At the end of 1924, a plan was proposed to “increase the scope and influence of the magazine” by instituting a fifty-cent subscription rate and soliciting advertisers. Subsequent issues demonstrated that the plan was ineffective or never implemented. The only advertisements that appeared in those issues were for council publications and pamphlets. No published record of circulation appeared in any of the issues.

By 1925, the magazine had made the transition from an in-house organ to a more nationally oriented publication. The tensions between modernity and assimilation were investigated in articles such as “Is the Modern Girl Different?” and “Has Suffrage Caught Our Women Unprepared?” The status of Jews in America was explored in articles concerning the importance of Jewish education, unifying Judaism’s branches, and opposing Bible instruction in public schools. That same year, The Jewish Woman also reported that the pendulum had swung back in favor of reinvigorating American Jewish practice with more tradition and “ceremony.”

Although the articles continued to keep pace with current events, in 1927 the magazine began to shrink in size—pared down to three or four articles from the usual six to eight. The editorials from those years summarized the achievements of the council rather than commenting on international and national issues. The last issue of The Jewish Woman appeared in October of 1931, without comment on cessation of publication. However, the legacy of The Jewish Woman is the example it set by continuously aiming to serve as “a platform that would unite all Jewish women in the interests that they share in common.”

The Jewish Woman 1–11 (1921–1931).

Rogow, Faith. Gone to Another Meeting: The National Council of Jewish Women, 1893–1993 (1993).