Before the twentieth century, much of the responsibility for caring for the needy—the poor, recent immigrants, or the disabled—fell to private groups or charitable individuals. Even today, when government assistance may help people in need, private organizations continue to play crucial roles in providing essential social services.

In the nineteenth century, American women began to play important roles in providing social welfare services. Few middle-class women of the era held paying jobs, for most Americans believed that women should focus on the private world of the home and family and leave public activities to men. Unpaid philanthropic work, however, was considered acceptable—indeed highly desirable—for women, for it was viewed as an extension of their roles as caregivers beyond the household to the wider community. In addition to dispensing charity individually, many women created benevolent societies, often devoted to assisting needy women and children.

Rebecca Gratz, a well-known Jewish community activist in Philadelphia, founded one of the earliest Jewish women’s organizations (and America’s first non-synagogue-based Jewish charity) in 1819, when she brought together several prominent Jewish women to create the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society. Dedicated to assisting the city’s Jewish women and children, the FHBS provided food, fuel, shelter, and later an employment bureau and traveler’s aid service.

Over the next decades, similar organizations developed around the country. In small Jewish communities, the ladies’ charitable society and the synagogue were often the only Jewish communal institutions. Other groups, such as sewing societies, allowed women to apply their domestic skills to philanthropic work. Women also founded “sisterhoods of personal service” to perform relief work among poor immigrant Jews.

In addition to providing much-needed assistance to those in need, Jewish women’s philanthropic organizations also played important roles in the lives of their members. Unable to vote, hold office, or work in most professions, women found in these organizations valuable opportunities to exercise leadership and authority. For Jewish women, whose religious obligations were more limited than those of men, charitable work was also an important spiritual outlet.

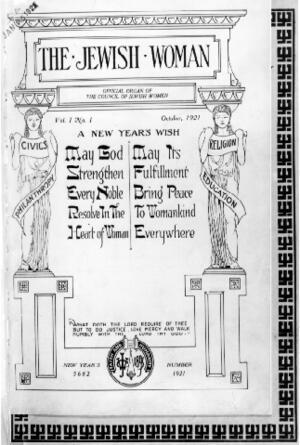

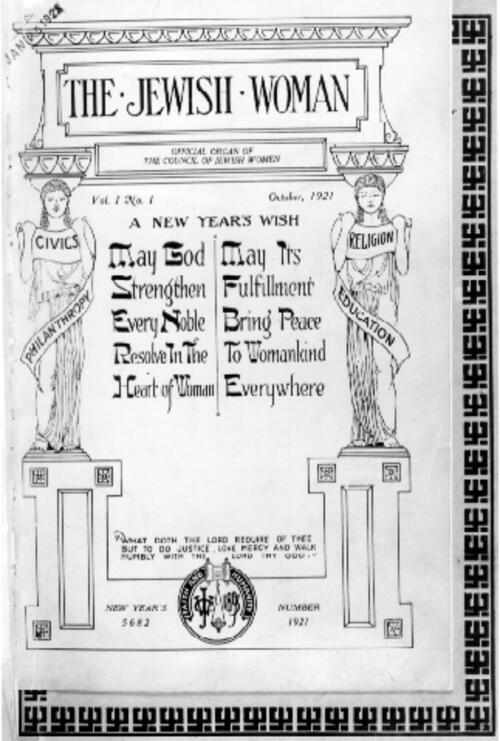

One Jewish women’s organization that grew out of this 19th century female philanthropic tradition and remains active today is the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW). Founded in 1893, NCJW was the first national organization of Jewish women. It quickly became a leader in the field of immigrant aid, bringing innovative ideas and organization to Jewish social welfare work. Maintaining an emphasis on women, motherhood, and families, it focused especially on programs to help immigrant girls adjust to American life without giving up their Jewish identity. NCJW assisted more than 20,000 Jewish girls who arrived in the United States without parents or guardians.

After World War II, NCJW’s immigrant aid programs helped refugees from the Holocaust remake their lives in the United States. It also shared its knowledge in the fields of immigrant aid, social work, education, and child care with the new State of Israel. In recent years, NCJW has continued its focus on the well-being of women, children, and families. It has been a consistent advocate for women’s reproductive health and rights and has conducted important studies and policy work on day care, child abuse, and domestic violence.

When NCJW was formed, most of its members strongly emphasized the importance of women’s duties as wives and mothers. Ironically, however, their commitment to traditional values led them to carve out new roles for Jewish women and broaden definitions of appropriate activities for women. NCJW members themselves often became important figures in their communities, helping to expand the public presence of women in Jewish communal life.

In addition to working in all-female associations, women have also participated in general Jewish charitable institutions. Historically, women found their ability to play key roles and in these organizations severely limited, but in recent decades, this situation has begun to improve. For example, in 1975, only 17% of the board members of Jewish Federation members were women, but that number had risen to 32% by 1993. Even as women’s opportunities in general Jewish organizations have widened, however, both national and local women’s organizations have continued to play important roles in the Jewish community.