Rebecca Gratz

As the founder and secretary of Philadelphia's earliest women's philanthropic organizations, Rebecca Gratz helped define a new identity for American women. Like other women of her era, Gratz believed that benevolent work was an appropriate extension of women's roles so long as it was done quietly. She devoted her adult life to providing relief for Philadelphia's underprivileged women and children and securing religious, moral and material sustenance for all of Philadelphia's Jews. An observant Jew living in a predominantly Christian nineteenth century culture, Gratz integrated her American experience and Jewish identity to establish the first American Jewish institutions run by women, including the first Hebrew Sunday School and Jewish Orphanage. She believed that women were uniquely responsible for ensuring the preservation of Jewish life in America and worked to create an environment in which women could be fully Jewish and fully American.

Notes:

- "You have heard..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, February 9, 1822. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)53.

- "misfortunes...lose us friends" Rebecca Gratz to Maria Fenno Hoffman, April 6, 1823, Rebecca Gratz Papers, Manuscript Collection no. 236. Courtesy of The Jacob Rader Marcus Center at the American Jewish Archives Cincinnati Campus, Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, OH.

- "how abundantly the..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, October 12, 1834. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929) 210.

Birth

Rebecca Gratz was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania on March 4, 1781. She was the seventh of twelve children born to Miriam Simon and Michael Gratz. Miriam Simon was the daughter of Joseph Simon, a preeminent Jewish merchant of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Michael Gratz descended from a long line of respected rabbis. Orphaned at an early age, he and his brother Barnard immigrated to Philadelphia from Silesia (now Germany), and amassed considerable wealth as merchants.

At the end of the 18th century, Philadelphia, the nation's capital, was the most religiously and ethnically diverse American city; the Gratz family traveled in its top social circles. Miriam and Michael were observant Jews who were also active members of Philadelphia's earliest synagogue, Mikveh Israel, and their small Jewish community. They were very concerned about their children's education and acquired a considerable library for them. Their efforts were well rewarded; Rebecca's older sister, Richea, was the first woman to attend college in America. As a child, Rebecca read avidly and particularly enjoyed history and literary classics. Her formal education is not well documented, but she may have attended the Young Ladies Academy, a well-known girl's school in Philadelphia.

Yellow Fever Epidemic

"Calamity fills our city.... Poor Maria and poor Harriet!... Left orphans at a period in life when the...care of a watchful, tender parent was most necessary...to confirm in their hearts the love of virtue.... Who can guide [them] through the many difficulties which... often obstruct a female's passage through this world of care?"

Although Gratz grew up in an observant Jewish household, many of her closest friends were not Jewish. Maria Fenno, the daughter of the prominent publisher John Fenno, was a particularly close friend and confidante of Rebecca's. The two young women often discussed their ideas about friendship, social relations, and the opposite sex. When the yellow fever epidemic of 1798 killed Maria's parents, Gratz was deeply affected. The tragedy, which was repeated in many Philadelphia homes, sensitized Gratz early to the effects of misfortune and the plight of orphans. Although Fenno moved to New York to live with relatives soon after the death of her parents, she and Gratz continued to correspond throughout their lives.

Notes:

- "Calamity fills our city..." Letter from Rebecca Gratz to Rachel Gratz, September 9, 1798, Gratz Family Papers, Collection no.72 box 15. Courtesy of the The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Literary Activities

In her late teens, the lively, beautiful, and articulate Gratz took her place among the social and literary elite of Philadelphia. Philadelphia was a growing cultural center and Gratz came to know many of the important thinkers of her era. She corresponded regularly with Maria Edgeworth, the British educator and novelist, Catherine Sedgwick, the American author, Fanny Kemble, the British actress, Grace Aguilar, the Jewish-British theologian, and many others. Gratz was also familiar with many of the nation's leading artists including, Thomas Sully, Edward Malbone and Gilbert Stuart, all of whom painted Gratz family portraits. Gratz's friends and family encouraged her to submit her own poetry to the Port Folio, a popular literary magazine. However, Gratz was never interested in fame; instead she used her writing talents in prolific correspondence and anonymous organizational reports.

Nurses Father

"Oh Sally! Each morning that I enter his chamber to take breakfast I am tortured with ten thousand pangs.... With fortitude should not a daughter stand the trial?"

When she was nineteen, Gratz's father, Micheal Gratz, suffered a debilitating stroke. Her brothers, Simon and Hyman, took over the family business and Rebecca became her bedridden father's caretaker. Although Gratz did not at first enjoy this role, she, like other single women of her era, became the family nurse. She went on to attend the births of many of her twenty-seven nieces and nephews and continued to take care of her sick relatives throughout her life.

Notes:

- "Oh sally!..." Letter from Rebecca Gratz to Sarah Gratz, July 28, 1800, Gratz Family Papers, Collection no. 72, box 21. Courtesy of the The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Female Association

"How hard... it is to have the tastes, the habits, the longings and recollections, if not of affluence, at least of comfort, and yet to be poor."

Young women of Gratz's class and era filled their time with social activities and family duties. Gratz, however, like other members of her family, became involved in benevolent work. In 1801, she, along with her mother, sister and twenty-one other prominent women, founded Philadelphia's first nonsectarian women's charitable organization, The Female Association for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstances. The Assocation sought to aid honest, industrious women who had fallen upon misfortune. It became a model for most of the women's organizations Gratz would later help to establish—women made all the decisions and accomplished all aspects of the organization's work, including the management of funds. Because of her proficiency as a writer, Gratz became the organization's secretary and served for twenty-two years. As secretary, she took minutes, handled correspondence, authored annual reports, and wrote all other public documents for the organization.

Notes:

- "How hard..." Female Association for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstance Constitution. Courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Deaths & Marriages

"You must banish reserve now, My dear Maria for we are Sisters, and with that loved title you have a claim to my warmest affection—and in that title too I look for such love as has been the most fertile source of comfort and happiness to me thro' my life. (Henceforth, we will not remember that there is a difference of opinion on any subject between us)."

After the deaths of their mother in 1808 and father in 1811, the unmarried Gratz siblings, Hyman, Joseph, Jacob, Sarah, and Rebecca remained in the family home. Rebecca was not eager to marry, for she thought "there appears no condition in human life more afflictive and destructive to happiness & morals than... an ill-advised marriage." Nevertheless, she "upbraid[ed her] bachelor brothers for continuing in their single state. A bad example in the eldest seems to afflict them, and I fear we shall all grow old together in the family mansion." Although Sarah died in 1817, Rebecca and her three brothers continued to live together for the rest of their long lives. In addition to performing household and family duties, they participated in both Jewish and non-sectarian communal activities.

The Gratz siblings were involved in a variety of organizations including Mikveh Israel's board of directors, Philadelphia's Anthenaeum, the Deaf and Dumb Home, the Chestnut Street Theater, the Academy of Fine Arts, and various libraries. Of the other five Gratz siblings to survive to adulthood, only the women, Frances, Richea, and Rachel, married Jews. Gratz, like other Jews in her predominantly Christian society, was very tolerant of others' beliefs and welcomed Simon's and Benjamin's non-Jewish brides. In fact, she became particularly close with Benjamin's wife, Maria Gist.

Notes:

- "You must banish..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, 1819. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)21.

- "there appears no..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Ann Boswell Gratz, May 27, 1847. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)21.

- "upbraid[ed her]bachelor..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Fenno Hoffman, October 28, 1812, Gratz Family Papers P8. Courtesy of The American Jewish Historical Society, Waltham MA & New York, NY.

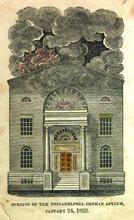

Philadelphia Orphan Asylum

"You have heard of the more dreadful calamity we have experienced in the destructive fire of the Orphan Asylum, and I am sure have sympathized with our distress—poor little souls how sad their fate!"

Gratz's work with the Female Association exposed her to the plight of poor widows and orphans in her community. In 1815, she helped found the Philadelphia Orphan Society, a private non-sectarian organization that sheltered and educated poor orphaned children until they were old enough to be apprenticed to families. Gratz soon became secretary of the board, a key leadership position that she held for more than 40 years. Through her work, Gratz gained community respect and admiration, and became an important figure in her own right. Shortly after the institution's founding, however, it suffered a terrible tragedy. In 1822, twenty-three of the 106 children who were living in the facility were killed in a fire. Gratz helped raise funds to rebuild a new asylum. As a fundraiser, she understood that "misfortunes... lose us friends" and worked hard to restore public faith in the institution and in the value of women's benevolent work. Gratz's success was well known, and she and the POA became consultants to other women who hoped to establish similar asylums. She commented in 1834, "How abundantly the good seed spreads when planted."

Family Religious School

Gratz became increasingly concerned about religious issues after her sister Sarah's death in 1817. In response to the burgeoning Christian Sunday School movement and increased religious fervor, Gratz began to perceive a need for Jewish education among women and children. In 1818, she began a small religious school for her siblings and their children. Although this early experiment did not expand beyond her family members, it convinced Gratz that this kind of training was essential for Jews living as minorities in a Christian world. Bar Mitzvah preparation and private tutorials were the only avenues of formal Jewish education available for boys, and there were none at all for girls. The family school became the prototype for the Hebrew Sunday School that Gratz would establish twenty years later.

Female Hebrew Benevolent Society

"Piety, self respect and charity will...make our wilderness bloom."

Gratz's experience with the Female Association and the Philadelphia Orphan Asylum had led her to believe that women, because of their aptitude for domestic duties, were particularly equipped to take care of the greater "house of Israel." Because her work with nonsectarian charitable organizations had convinced Gratz that even the most well meaning Christians were often eager to convert others, she became concerned about the growing number of needy Philadelphian Jews.

In 1819, she helped establish the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society to create a Jewish presence in the benevolent community. Gratz believed "it is not too much to hope—too much to expect from the daughters of a noble race that they will be foremost in the work of Charity— provided their young hearts are impressed with its sacred duties." The society provided Philadelphia's impoverished Jews with food, clothing, fuel, and other necessities. Like the Female Association, the Society sought to protect the poor without encouraging pauperism. The Society was the first non-synagogue Jewish women's organization in North America and did not require its clients to attend religious services or belong to a congregation. Again, Gratz chose to be the organization's secretary and served in that capacity for nearly forty years. She hoped to build women's stature in the Jewish community and show that Jews could take care of themselves.

The Female Hebrew Benevolent Society of Philadelphia remains the oldest Jewish charitable organization in continuous existence in the United States.

Notes:

- "Piety, self respect..." From a "Report," published by The Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, 1835. Gratz Family Papers, Collection no.72, box 17, p.145. Courtesy of The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

- "it is not too much..." From a "Report," published by The Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, 1835. Gratz Family Papers, Collection no.72, box 17, p.143. Courtesy of The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

"Ivanhoe" Legend

"Have you received Ivanhoe? When you read it tell me what you think of my namesake Rebecca."

In 1820, Sir Walter Scott published the novel, Ivanhoe, whose heroine Rebecca, was a beautiful Jewess who refused to marry out of her faith. Soon after the book was published, it was rumored that Rebecca Gratz was the model for Scott's dashing medieval Rebecca. Although there is no direct evidence linking Gratz to the novel and no indication that Gratz was ever romantically involved with anyone, Jewish or Christian, the legend has persisted. The origin of the myth lies in a rumored conversation between Washington Irving (a friend of Gratz's) and Scott. Supposedly, Scott sent Irving a copy of the novel with a letter asking Irving if he recognized "his Rebecca." This letter has never been found.

Like Scott's Rebecca, however, Gratz was beautiful and talented and chose to remain single in a world that regarded marriage as a woman's primary role. The Ivanhoe legend has given generations of Jewish-Americans a way to explain the accomplishments of a woman who defied traditional notions of achieving status in the Jewish community. Whether or not the legend is true, Gratz herself found Scott's work gratifying. In 1829, she wrote to her old friend Maria Fenno Hoffman, "I felt a little extra pleasure from Rebecca's being a Hebrew maiden. It is worthy of Scott in a period when persecution has re-commenced in Europe to hold up a picture of the superstition and cruelty in which it originated."

Notes:

- "Have you received ..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, April4, 1820. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)29.

- "I felt a little extra..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Fenno Hoffman, March 25, 1813 Gratz Family Papers, p29. Courtesy of The American Jewish Historical Society, Waltham MA & New York, NY.

Takes in Sister's Children

"I love children—and childrens talk—their own words expressing their own thoughts goes quicker to my heart than anything wiser that is said for them."

Gratz adored her nieces and nephews and thought, "children are very good society. " She was particularly close to her sister Rachel's six children and considered them her, "favorite toys." In 1823, when Rachel died in childbirth, Gratz resigned from the Female Association's board and brought the children home to live with her. In 1825, the children's father, Solomon Moses, bought a house across the street from the Gratz family home and took the older children back to live with him. Nevertheless Gratz continued to help raise the children, and became a second mother to her nieces and nephews.

Notes:

- "I love children..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, March 12, 1826. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)83.

- "children are very good society" From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Fenno Hoffman, March 25, 1813 Gratz Family Papers, p8. Courtesy of The American Jewish Historical Society, Waltham MA & New York, NY.

- "favorite toys" From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Fenno Hoffman, ca. 1815,Rebecca Gratz Papers, Manuscript Collection no. 236. Courtesy of The Jacob Rader Marcus Center at the American Jewish Archives Cincinnati Campus, Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, OH.

Religious Tolerance

Gratz remained actively involved in the Philadelphia Orphan Asylum for more than forty years. Deeply committed to the cause, she served not only as secretary of the board, but was also an active fundraiser for the organization. In addition Gratz advised on the subject of running an orphanage, Gratz advised other women, including her sister-in-law, Maria Gist Gratz in Lexington, KY, on establishing their own institutions.

As a respected member of the benevolent community Gratz was afforded special status. Kind, charitable and hard working, she was accepted on the boards of charitable institutions in spite of her Judaism. Gratz was conscious of such distinctions and was put off by the sectarianism of the asylum managers. Things came to a head one day when Gratz's application for her friend Mrs. Furness to adopt a child was denied. As she wrote: "You know I promised our friend Mrs. Furness to apply for a little girl out of the asylum for her—well there is a good little girl I have kept my eye on and she is ready for a place—and my application is rejected because it is for a Unitarian— (but 'Ladies, said I, there are many children under my special direction—you all know my creed—suppose I should want to bring up one in my family?'— 'you may have one, said a church woman—because Jews do not think it a duty to convert.') I am ashamed of such an illiberal spirit.... What a pity that the best and holiest gift of God...should be perverted into a subject of strife."

Notes:

- "You know I promised..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, 1832. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)145.

Hebrew Sunday School

"I am gratified in the improvement of a large class of children...it will be a consolation for much lost time—if this late attempt to improve the degenerate portion of a once great people shall lead to some good—and induce wiser and better Jews to take the work in hand."

By the 1830s Gratz had become increasingly concerned about the future of Philadelphia's 750 Jews. In 1835, she urged the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society to address, "that most pressing need— the mental impoverishment of those who are rising to take their places among the thousands of Israel scattered throughout the families of the earth." Her solution was a Jewish educational program modeled on the Christian Sunday Schools which had successfully taught thousands of children all over the United States the fundamentals of reading and Christianity. In 1838, the Society resolved that "a Sunday school be established under the direction of the board, and teachers appointed among young ladies of the congregation." The school opened three weeks later, on Gratz' fifty-seventh birthday, with sixty students enrolled. Gratz became the school's superintendent and served for more than twenty-five years.

She worked tirelessly for the school, personally grading each student's homework assignments and creating materials for the students' use. Rebecca Gratz's grandniece, Miriam Mordecai, later remembered how family members had "helped 'Aunt Becky' paste little slips of paper over objectionable words or sentences" in books published by the Christian American Sunday School Union that the Hebrew Sunday School used. The school was radically different from traditional Jewish education programs; it was coeducational, met only once a week, and lessons were taught in English instead of Hebrew. In addition, the school was run entirely by women and was the first Jewish institution to give women a public role in the education of Jewish children. The model spread quickly and Gratz advised women in Charleston, Savannah, and Baltimore on establishing similar schools in their own communities.

Notes:

- "I am gratified..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, February 23, 1840. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929).

- "that most pressing..." From a "Report," published by The Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, 1835, Gratz Family Papers, Collection no.72, box 17, p143. Courtesy of The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

- "a Sunday school..." From a "Report," published by The Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, 1835, Gratz Family Papers, Collection no.72, box 17, p143. Courtesy of The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

- "helped ‘Aunt Becky’..." Mordechai, Sara, Recollections of my Aunt: Rebecca Gratz, 1893. p.7.

Jewish Foster Home

In her 70s, Gratz had come to be seen as a visionary and indispensable community leader. By the 1850's, the Hebrew Sunday School was an established institution, but a growing number of poor Jewish children were still being sent to live in non-Jewish orphanages. Gratz's experience at the POA made her aware that even non-sectarian institutions had a Christian focus that could undermine a child's Jewish convictions. By 1844, Gratz had begun to lobby the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society to create a Jewish orphanage. Her friend and teacher Isaac Leeser recommended that she write an article to rally support in The Occident, a magazine widely read in the Jewish community. Leeser hoped to link the Gratz name to the institution and was upset when Gratz declined because she believed that "the more quietly [people] go about doing good the better." Eventually the two compromised; Gratz agreed to write the letter, but the article rallying support for the Home was published anonymously under the pseudonym "a daughter in Israel." In 1855, the Home, which received children from all over the United States and Canada, finally opened. The Jewish Foster Home was the first Jewish orphanage in the U.S. and was made possible by donations from across North America. At the age of 74, Gratz was elected secretary of the Jewish Foster Home. Nevertheless, she continued to sit on the boards of the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, the Philadelphia Orphan Asylum, and remained the superintendent of the Hebrew Sunday School for several more years.

Notes:

- "the more quietly..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Isaac Leeser, November 9, 1849 Rebecca Gratz Papers, Manuscript Collection no. 236. Courtesy of The Jacob Rader Marcus Center at the American Jewish Archives Cincinnati Campus, Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, OH.

Civil War

While Gratz did not see herself as a political or public person, she held strong opinions about slavery and sectionalism and used her influence to assert them. Her siblings, nieces, and nephews were scattered throughout the North and the South and Gratz tried to maintain contact and provide moral counsel to all of them. She regularly admonished her brother Benjamin's second wife, Ann, that "one of the curses of slavery is the entire dependence the poor mistress is reduced to." When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Gratz was disturbed that members of her family would be on opposing sides. As she wrote to Ann, "I have been reading some loving letters from some so near to me in blood and affections whose arms are perhaps now raised against those hearts at which they have fed."

Notes:

- "one of the curses..." From a letter from Rebecca Gratz to Maria Gist Gratz, November 11, 1820. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)198.

- "I have been reading..." Rebecca Gratz to Ann Boswell Gratz, September 12, 1861. From Letters of Rebecca Gratz, edited by David Philipson. (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929)227.

Legacy

"The crowning happiness of my days has been my association with my beloved companions [the teachers and managers of the Hebrew Sunday School] in the duties we have shared together."

Rebecca Gratz died on August 27, 1869. Although she outlived all but her youngest sibling, Benjamin, most of her friends, and many of her nieces and nephews, she remained actively involved on the boards of the Philadelphia Orphan Society, Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, Hebrew Sunday School and Jewish Foster Home well into her eighties. Gratz's enduring legacy can be measured by the success and longevity of the many institutions she founded. The Philadelphia Orphan Society and Female Association provided material sustenance to thousands of women and children. The Jewish Foster Home thrived until it eventually merged with other institutions to create the Philadelphia Association for Jewish Children. The Female Hebrew Benevolent Society and Hebrew Sunday School continued their work for almost 150 years. In 1986, the flourishing School merged with the Talmud Torah Schools of Philadelphia and continues to provide coeducational Jewish learning for thousands of young students. As historian Dianne Ashton writes, "By training younger Jewish women in administering the agencies she founded, Gratz ensured that the FHBS, HSS and JFH would continue to flourish long after her death. In their work, these organizations continued to provide Jewish women and children a way to be both fully Jewish and fully American."

Notes:

- "The crowning happiness..." From the Minutes of the Hebrew Sunday School, 1860-1880. The Jacob Rader Marcus Center at the American Jewish Archives Cincinnati Campus, Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati, OH.

- "By training younger..." Ashton, Dianne Rebecca Gratz. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press 1997).

Media

Timeline

Birth

Yellow Fever Epidemic

Literary Activities

Nurses Father

Female Association

Deaths & Marriages

Philadelphia Orphan Asylum

Family Religious School

Female Hebrew Benevolent Society

Ivanhoe Legend

Takes in Sister's Children

Religious Tolerance

Hebrew Sunday School

Jewish Foster Home

Civil War

Legacy

Bibliography

Published Sources

American Sunday School Union. A History of the Orphan Asylum in Philadelphia. Philadelphia: American Sunday School Union, 1832.

Ashton, Dianne. Rebecca Gratz. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997.

Mordechai, Sara. Recollections of My Aunt: Rebecca Gratz. 1893.

The Occident. April, 8(1):1850.

Philadelphia Orphan Society. First Annual Report of the Philadelphia Orphan Society. Philadelphia: Order of the Philadelphia Orphan Society, 1816.

Philipson, David ed. Letters of Rebecca Gratz. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1929.

Scott, Sir Walter, Ivanhoe. Dodd, Mead & Company, 1943.

Archival Sources

The American Jewish Historical Society. New York, NY.

The American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia, PA.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA.

The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati Campus, Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion,Cincinnati, OH.

The Library Company of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, PA.The National Museum of American Jewish History. Philadelphia, PA.

The Philadelphia Jewish Archives Center. Philadelphia, PA.

The Rosenbach Museum & Library. Philadelphia, PA.

I would like to know where the orphan records are kept. We are researching the case of America's Unknown Boy who was found dead in 1955. Case is cold/unsolved. He may have come from an orphanage. Anything you can help with would be most appreciated. For more information on this case look up America's Unknown Boy.

Thanks!