Iraqi Jewish Women

Jews lived in Iraq for thousands of years. Life for Iraqi Jewish women was determined by tradition, custom, and religious law, with a patriarchal system that emphasized child-rearing and household duties. In its treatment of women, the community was profoundly influenced not only by Islamic society, but also by class. The British Mandate period brought socio-economic prosperity, modernity, secularization, and the expansion of the middle class, to the extent that some Iraqi Jews wanted their daughters to be educated to enhance their prospects in choosing a better partner in marriage. Most Iraqi girls, however, were still not educated. Most women did not work outside the home until mass migration to Israel in the mid-twentieth century, when they were forced for economic reasons to work and life for Iraqi Jewish women changed due to assimilation.

Introduction

“When Rachma had a son the well-wishers congratulated the family with ‘B’siman Tov’ [good fortune] and ‘Tesewihum Sab-a’ [may there be seven], but when she had a daughter they merely said ‘Mazal Tov’ [good luck], sometimes adding what were in effect words of sympathy, ‘Al-Hamd Lilah Ala Salamitha’ [thank God the mother is well] and ‘Ala Rasa Libnin’ [may boys follow her]” (Cohen 1973, 1996; Zenner 1982). Sons were preferred to daughters and this is still the case, though it is no longer expressed so openly. When Rachel gave birth in Israel to her first child, a girl, her parents-in-law decided to cancel their planned visit from America. Rachel commented “My in-laws may consider themselves educated and modern [they were born in America], but they behave as if they were living in Iraq.” When she gave birth to a boy, her second child, they arrived within a week and stayed for three months. “My mother-in-law argued that I needed some help. After all, ‘giving birth to a boy is strenuous!’” To be called Abu-le’bnat (the father of girls) is an almost derogatory term. Contrariwise, giving birth to a boy can elevate a woman’s status in her husband’s eyes and therefore her standing in the family and community.

The behavioral characteristics of Jewish women in Iraq were modeled according to tradition, custom, and religious law. In its treatment of women, the community was profoundly influenced not only by Islamic society, but also by the class system within the community. Women of affluent status fared better than those of lower class.

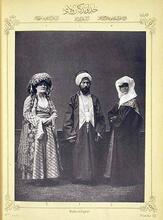

Indeed, the Jewish community in Iraq was divided according to a rigid class structure and based on a hierarchical patriarchic system (Deshen 2001) in which women were inferior and isolated from the rest of the society. Until the mid–1930s, outside their homes the majority had to cover their head and wear a veil over their face and a cloak to cover their body. In this society women’s needs and feelings were given little if any consideration; their duties were child-bearing, preferably of boys, serving their husbands’ needs, and educating their daughters to become submissive and to manage the household duties when they married. A girl moved from the authority of her father to the authority of her husband, after which she was supervised by her mother-in-law. (Sehayik 1988; Yiftach 1999)

Education

Iraqi Jewry underwent major social changes during the middle of the nineteenth century, following the opening of the boys’ school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Baghdad in 1864. In 1893, the opening of the girls’ schools met with extreme opposition, including that of the older women. Following the success of the first Jewish schools many more were opened in other cities in Iraq to meet the growing demand for Jewish schools for girls and, more particularly, for boys. By 1911 Alliance Israélite Universelle had opened four schools for girls. By 1900, 132 girls were studying in primary schools and by 1910 this number had tripled to 399; by 1921, when the population numbered fifty thousand, there were 1,481 girl pupils, and by 1948, when the Jewish population was approximately ninety to one hundred thousand, there were thirty-two schools and 3,818 girl pupils.

The Mandate for Palestine given to Great Britain by the League of Nations in April 1920 to administer Palestine and establish a national home for the Jewish people. It was terminated with the establishment of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.British Mandate brought about socio-economic prosperity, modernity, and secularization and the expansion of the middle class, to the extent that several of its members wanted their daughters to be educated to enhance their prospects in choosing a better partner in marriage. Nevertheless, the majority still objected to educating girls. In the case of girls who had the misfortune of having a birth defect or of being exceptionally ugly, it was assumed that they would not be able to find a husband; they were therefore sent to schools to acquire a profession so that they could take care of themselves when their parents died and if they could not live in their brothers’ households. In school for four years (sometimes less), girls learned reading and writing, Bible studies, home economics and particularly dressmaking, to enable them, once married, to manage their homes efficiently and carry out their domestic duties (Watson and Ebrey 1991). Boys, on the other hand, were taught several languages, economics, accountancy, etc. They sat for English and French matriculation and graduation certificates.

From the mid–1930s girls were accepted into government schools and a few graduated from teacher college. At the same time girls between the ages of fifteen to eighteen were allowed to study in the Shamash Jewish High School, and in 1941 eight females graduated from the school of law in Baghdad. From the end of the 1930s Jewish, Muslim, and Christian girls were allowed to enter the higher schools of law, medicine, economics, and pharmacy. Between 1941 and 1959 fifty Jewish women graduated from these faculties. In all these schools women were separated from men in the classroom and in the yard (Sehayik 1988). But ,their numbers were very small, as is borne out by the fact that the 1961 Israeli Census shows that among Iraqi Jews (including Kurdish Jews) twenty-six percent of men and nearly sixty percent of women were illiterate (Meir-Glizenstein 2000). The schools in fact catered to a small percentage of children from the upper and upper-middle classes. Though the Jewish woman was better off than her Muslim and Christian counterpart, the rapid socio-economic changes, modernity, and secularization had little impact on women’s inferior status.

Choosing a Partner: Love, Marriage and Arrange Marriage

Among traditional Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardim, “negotiating a suitable match and delivering one’s daughter into marriage was considered a father’s obligation” (Gale 1994, 61; Friedman 1980; Patai 1960; Epstein 1973). The father was the master of his family and tradition legitimized his actions and his control over his wife and children (Katz 1982; Watson and Ebrey 1991; Layish and Shaham 1991). A girl could rarely object to her parents’ choice.

The birth of a girl was considered to be a burden on the family and from her birth they began to accumulate a dowry for her. Many girls never married because their parents did not have the money for a dowry. Numerous marriage promises were broken over disputes concerning the size of the dowry.

Until the end of the nineteenth century, girls were married at the age of twelve or thirteen, and sometimes even at eleven (Shokeid and Deshen 1974; Ben-Ya’acob 1985; Layish and Shaham 1991). By about 1913 the age had been raised to fifteen (Cohen 1996). Since families were eager to marry off their daughters as soon as possible, the government issued a ruling that girls of high class would not be contracted in marriage before the age of ten, girls of the middle class not before they reached eleven years of age, and poor girls not before the age of twelve. This was to protect the poor girls from the eagerness of their families to give them away to anyone (Gale 1988; Sehayik 1988). The rabbis and heads of communities attempted to limit the size of the dowry and issued a Regulation supplementing the laws of the Torah enacted by a halakhic authority.takkanah to stop the custom of sending expensive presents to the bridegroom and his family, but all to no avail; the community continued with these customs, causing misery to many women.

Age, beauty, and wealth were important attributes that increased a woman’s chances of attracting a husband from a good family. At a later stage, the basic education of the woman also became advantageous, yet without a sizeable dowry her chances of marrying were limited indeed. On the other hand, wealth and power gave older men privileges and families who could not afford the dowry gave their young daughter to an older man prepared to waive the dowry. However, many parents declined the waiving of a dowry in order to protect their daughters from an abusive husband.

While both men and boys were also often forced into unwanted marriages, women seem to have been heavily disadvantaged. The wishes and desires of the family were far more important than those of the individuals concerned, since the main focus when contracting a marriage was on the family—its honor, status, and wellbeing—rather than on the compatibility of the spouses (Bulka 1986, 79). In choosing marital partners for its members, families usually focused on the social standing and the wealth of the family of the prospective spouse and the beauty of the prospective wife. Dowry size was also chiefly determined by these factors. Love was regarded as an unnecessary precondition to marriage. The young were socialized into reliance on and submission to parental judgment and authority, particularly that of the father (Friedman 1980). The wife’s personal property (the dowry) was for the use of her husband and controlled by him, as were the children, whose education and care he determined. In fact, some said that the large dowry ensured the welfare of the women, since this money, though for use only by the husband, still belonged to the wife; if the husband desired a divorce, he would have to return the dowry to her parents. Nevertheless, strict obedience was an essential component of the husband-wife relationship and a wife could seldom challenge her husband’s authority. Even after immigration to Israel most women remained with their husbands, despite the miserable life they had led in Iraq, as they were under the control of their authoritarian spouses and afraid of arousing the wrath of the community.

In 1924, with the influence of the Mandate for Palestine given to Great Britain by the League of Nations in April 1920 to administer Palestine and establish a national home for the Jewish people. It was terminated with the establishment of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.British Mandate and western culture, the The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic ruling of inheritance came under criticism by a few Iraqi Jews, who submitted a proposal to the Baghdadi Jewish community to the effect that daughters should receive half the inheritance that sons received, as the Muslims do. This was forcefully rejected by the heads of the community (Epstein 1973; Cohen 1973; Elon 1975). In the same year a group of young intellectuals demanded that the dowry custom be stopped and that men should provide for the household, as was practiced by the Muslims. This failed because the dowry custom was deeply entrenched in the tradition of the Jewish community in Iraq and men liked the fact that they were set up in business, with no financial worries. Furthermore they could choose their brides according to the size of the dowry.

After marriage the young couple moved in with the husband’s parents. The mother-in-law ruled the household with a strong hand while her unmarried daughters and her daughters-in-law were under her command. This type of cohabitation created many frictions within the household. Toward the mid–1930s a few couples moved out of the husband’s family home and set up an independent household, if they had the means and the approval of their families.

Polygyny

Bigamy (and polygyny) was more prevalent among Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardim and Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi Jews, as the Ashkenazi Rabbi Gershom ben Judah (Me’or ha-Golah, c. 960–1028) forbade it and his Ban; excommunication (generally applied by rabbinic authorities for disciplinary purposes).herem was accepted as binding among all Ashkenazi communities, but not among the Sephardi and most of the Oriental communities. Additionally, in those countries inhabited by Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazim, polygyny was forbidden by the dominant religion, Christianity, and thus, by extension, by secular law, whereas in those countries where Sephardim lived, polygyny was permitted by the dominant religion, Islam, and thus by the prevailing secular law as well (Elon 1975, 368).

Although permitted, polygyny was exercised on a very small scale until it virtually ceased at the beginning of the twentieth century. If a woman bore many girls, the rabbis sometimes permitted taking a second wife to increase the husband’s chances of having a boy. In that case everyone in the community sympathized with the husband and behind his back they might call him “abu-le’bnat.” A woman who was divorced for not conceiving had little chance of remarrying and she was better off remaining with her husband, who would take a second wife (Cohen 1973; Patai 1960). Almost unheard of in Iraq, divorce was considered a family tragedy and condemned by the community when it did occur. In fact, the rabbis made divorce difficult, instead advocating and facilitating polygyny—which was permitted by both Jews and Iraqi Muslims (Patai 1981; Cohen 1973; Elon 1975; Layish and Shaham 1991). However, such plural marriages were relatively rare.

Of the 27,042 Iraqi women who immigrated to Israel in 1950–1951 (most of whom were married), only 226 or 0.8 percent were divorced (Zenner 1982, 194–199; see also Solomon in Jewish Journal of Sociology 25, no. 2 (Dec. 1983): 131–140). In Israel the divorce rate among Iraqi women is not as high as that within society in general. However, compatibility is given more weight than it was in the countries of origin, where the rabbis and the community did not consider it a sufficient reason to divorce.

If a husband died childless, Jewish law demanded that his widow marry his brother in a Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).Levirate marriage (yibbum), to produce a son to carry on the deceased’s name. If the brother-in-law did not want her, or if she could convince him that such a marriage would not be beneficial to either party, a halizah ceremony was performed, releasing her from the levirate tie and freeing her to marry someone else. (The custom of levirate marriage, as prescribed in Deuteronomy 25:5-6, was practiced by Jewish communities in Iraq long after it had been replaced by Mandated ceremony (Deut. 25:9halizah in the Ashkenazi communities, where the rabbis usually pressured the deceased’s brother to free his sister-in-law. According to the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, levirate marriage is obligatory only when the deceased husband did not produce offspring, although the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah calls for such marriages only when a male has not been born. Ashkenazim tended to follow the practice of halizah, but the Sephardim continued to follow the custom of the levirate marriage in their countries of origin. In 1950, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel prohibited levirate marriages and made halizah obligatory, in order to keep the law of the Torah uniform for all [Elon 1975, 403–409].)

Occupation

Most women did not work outside the home. Rabbis and leaders of Jewish communities in Iraq encouraged the seclusion of women from public and religious life under the assumption that danger abounded outside the home. Furthermore, Jews considered women’s physical work and other employment as demeaning. But ,the needy, widows, and divorced women worked in their own homes in dressmaking, embroidery, weaving, midwifery, and nursing, and as matchmakers. All these occupations were to some degree tolerable, but very poor girls worked as servants, laundrywomen, singers and bakers, as musicians at weddings and as mourners in the houses of the deceased—professions that were considered inferior. From the mid–1930s a few women began to work as teachers, secretaries and in the free professions.

In Israel

Prior to immigration to Israel in the early 1950s the Jewish community numbered 125,000–150,000. In the early 2000s, the population of Jews of Iraqi origin in Israel was 249,200, of whom 172,200 were Israeli born. Approximately eighty-five percent were urbanized and the vast majority lived in the central part of Israel. The transition from a traditional to a Western society brought about many changes in the functions of the Iraqi family, which profoundly influenced the position of women. The cultural shock men suffered from was very intense for the Iraqi, particularly for those who were of middle and upper class in Iraq. Many of them refused to work in agriculture, considering it demeaning; in their eyes it was the employment of a fellahin (villager). Furthermore, they were very proud and many refused to go on the welfare system, rejecting “handouts.”

Women, on the other hand, were compelled by the economic situation to go out to work, although the majority were unaccustomed to working outside the home. They proved to be towers of strength to their husbands, who were suddenly forced to see their wives in a different light as auxiliary breadwinners. Prepared to accept whatever employment was available, women worked in many jobs in order to provide for their families—agriculture, cleaning, cooking, dressmaking, and other employment. As a matter of fact, many people preferred to employ Iraqi women rather than their husbands. The women never complained; after working from dawn to late afternoon, they came home to do the housework and care for the children. When the newcomers acclimated, women began to see themselves in a different light, appreciating their newly found strength. In other words, the fundamental change in the women’s position began with work outside the home (Hartman 1991), which was forced on them by the economic circumstances of the time and which turned many of them into the family’s sole breadwinners. As a result, women became more dominant in decision-making (Gale 1994, 70). Employment also led to a decline in birth rate and a rise in women’s age of marriage, both of which resulted in smaller families and a narrowing of the average age difference between husbands and wives. There was also a dramatic decrease in the number of kin marriages (Cohen 1973; Patai 1960, 1981).

The state stripped the family of many of its traditional customs, initially by enforcing compulsory education for males and females alike up to the age of fourteen (Benski 1991). Increased education also brought more women to the workforce, which resulted in professionalism and an increase in their social rights. Israeli-born Iraqi women seized the new opportunities. As a result of the 1977 law of compulsory education to the age of sixteen, most of the female youngsters completed high school education. Improvements through education of succeeding generations contribute to the mothers’ motivation to be involved in their children’s education (Nahon 1993). Among the smaller number of women who have completed tertiary education, many hold communal positions and have become more dominant both in the home and in their career. The marriageable age is higher. Israeli Family Laws have protected women’s welfare in the home. Compulsory service in the Israeli army has made women more independent. All these factors contributed fundamentally to the change in the position of women (Martin 1957, 1965; Layish and Shaham 1991). Male authority declined as the women took a greater part in household decision-making and also in determining to have fewer children (Gale 1988). Inter-ethnic marriages within the Sephardi as well as into the Ashkenazi groups have brought about more integration within Israeli society (Don 1991). However, there has also been a rise in the divorce rate (Morgan 1975, 87–101).

Young people not only choose their own partners but engage in a period of courting, so that they can get to know each other. Selecting one’s own partner is a function of Western society, which concerns itself with individual rights (Filsinger 1983). The choice of partner and marriage are defined as an achieved status by both spouses in the West (Schrieft 1989; Parsons 1956; Blood 1978, 138–144), though this choice is not free of the influence of social class, the status of the families, occupational position and tradition (Blood 1978). Thus many Iraqi men in Israel still prefer their wives to be either inferior or equal to themselves socially (i.e., in educational and professional background), as was the case when the community was more rigidly divided into classes in the country of origin (Layish 1994; Layish and Shaham 1991). Finally, whereas the dowry system was important on arrival in Israel, it has since been replaced by exchanges on both sides.

Occupations in Israel

Despite the extensive changes in family dynamics, there is still a very explicit division between the two sexes with regard to work and the professional occupational role is still viewed mainly as a masculine prerogative (Bar-Yosef 1991). In Israel a woman’s success in kinship, friendship and career depend on the extent to which she is able to define these roles as important to her—as distinct from the role of wife and mother. This, in turn, depends mainly on her level of education and type of socialization. Generally speaking, young women are able to cope with the various roles more successfully than older women because they have not been as rigidly socialized (Hartman 1980, 225–255). Although there has been some change in the upper-middle-class professionals’ attitude regarding married women and the domestic role, lower-middle, middle and upper-middle-class professionals all exhibit a similar pattern, in which husbands prefer their wives to stay at home, particularly if they can afford it financially. In most cases, women are employed full-time, but only in work, such as teaching, that is compatible with their homemaking responsibilities. Women expect—and are expected—to perform most of the domestic duties; “liberal” husbands do not “share” the housework but rather “help” their wives.

The transition to modern society has clearly given more power to women. Although daughters are still brought up to respect their parents, there has been a shift from blind obedience to compromise and sometimes even conflict. The decline in the birthrate has also played a major role in improving the welfare of women—the average family today has three or four children. The woman of Iraqi origin continues to move toward increased freedom of the individual from parental control: a “growing democratization in respect to sex and age differentiation… took place among Orientals during the last two decades.” (Smooha 1978, 114). Nevertheless Layish and Shaham (1991) argue that the father is still the primary executive member or head of the family. Many women in Israeli society still relate to their husbands as the head of the family, and within the family there is still division of labor, which is least flexible among the older generation and in particular among the Iraqi families who remain in the social and geographical periphery of Israel.

Bar-Yosef, Rivka. “Household Management in Two Types of Families in Israel” (Hebrew). In Families in Israel, edited by Leah Shamgar-Handelman and Rivka Bar-Yosef, 169–196. Jerusalem: Academon, 1991.

Benski, Tova. “The Dimension of Social Status.” In Iraqi Jews in Israel: Social and Economic Integration. Edited by Tova Benski et al., 171–196 (Hebrew). Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1991.

Ben-Ya’acob, Avraham. Babylonian Jewry in the Diaspora (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1985.

--- Babylonian Jewry from the Period of the Geonim until Today (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1965.

Blood, Robert. Marriage. New York: Free Press, 1978.

Bulka, Reuven Pinchas. Jewish Marriage: A Halachic Ethic. Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing, 1986.

Cohen, Haim J. The Jews of the Middle East, 1860–1972. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1973.

--- “A Note on the Social Change among Iraqi Jews 1917–1950.” Jewish Journal of Sociology 8 (1996): 204–218.

Deshen, Shlomo. “The Jews of Baghdad in the Nineteenth Century: The Growth of Social Classes and Multicultural Groups” (Hebrew). Zemanim 73 (2001): 30–44.

Deshen, Shlomo, and Walter P. Zenner, eds. Jewish Societies in the Middle East: Community, Culture and Authority. Washington D.C.: University Press of America, 1982.

Don, Yehuda. “The Iraqi Jews—Socio-Demographic Introduction.” In Iraqi Jews in Israel: Social and Economic Integration. Edited by Tova Benski et al., 11–56 (Hebrew). Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1991.

Elon, Menachem, ed. The Principles of Jewish Law. Jerusalem: Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1975.

Epstein, Louis M. The Jewish Marriage Contract: A Study in the Status of the Woman in Jewish Law. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 1973.

Filsinger, Eric E. “Love, Liking, and Individual Marital Adjustment: A Pilot Study of Relationship Changes within One Year.” International Journal of Sociology of the Family 13, no. 1 (1983): 145–157.

Friedman, Mordechai Akiva. Jewish Marriage in Palestine: A Cairo Geniza Study. Vol. 1, The Ketuba Traditions. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 1980.

Gale, Naomi. “From The Homeland to Sydney: Kinship, Religion, and Ethnicity among Sephardim.” PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, 1988.

--- “Love and Marriage, Past and Present: The Case of the Oriental Jews in Sydney.” International Journal of Sociology of the Family 24 (1994): 61–86.

Hartman, Harriet. “Division of Labour in Israeli Families.” In Families in Israel, edited by Leah Shamgar-Handelman and Rivka Bar-Yosef, 169–196 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Academon, 1991.

Hartman, Moshe. “The Role of Ethnicity in Married Women’s Economic Activity in Israel.” Ethnicity 7, no. 3 (1980): 225–255.

Katz, Jacob. “Traditional Society and Modern Society.” In Jewish Societies in the Middle East: Community, Culture and Authority, edited by Shlomo Deshen and Walter P. Zenner, 35–48. Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1982.

Layish, Aharon. Islamic Law in the Contemporary Middle East. London: Centre of Near & Middle Eastern Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, 1994.

Layish, Aharon, and Samuel Shaham. “Islamic Law in the Middle East.” The Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (1991): 1–29.

Lewis, Bernard. The Jews of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Meir-Glizenstein, Ester. “The Immigrants from Iraq and Israeli Policy in the Early 1950s and Their Struggle for Integration.” In The Zionism Era, edited by Anita Shapira, Yehuda Reinharz and Ya’akob Hariss, 271–295 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Shazar Center, 2000.

Martin, Jane I. “Marriage, the Family and Class.” In Marriage and the Family in Australia, edited by Adolphus Peter Elkin, 24–53. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1957.

--- “Report for the National Population Inquiry.” In Australian Society: A Sociological Introduction, edited by A. F. Davies and Sol Encel Australia: 1965.

Morgan, James Henry D. Social Theory and the Family. London: Routledge, 1975.

Nahon, Yaacov. “Educational Expansion and the Structure of Occupational Opportunities.” In Ethnic Communities in Israel—Socio-Economic Status, edited by N. Eisenstadt, Moshe Lissak and Yaacov Nahon, 33–49 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 1993.

Parsons, Talcott. and Bales, F. Robert. Family, Socialization and Interaction Process. London: Routledge, 1956.

--- “The Normal American Family.” In Man and Civilization: The Family Search for Survival, edited by Seymour M. Farber et. al., 31–50. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965.

Patai, Raphael. Family, Love and the Bible. London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1960.

--- The Vanished World of Jewry. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1981.

Schrieft, Ruth. “Marriage—Optional or a Trap?” In Trapped Women, edited by Dafna Izraeli. Tel Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuhad Press, 1989.

Sawdayee, Mourice. “The Impact of Western Education on the Jewish Millet of Baghdad 1860–1950.” PhD Dissertation, New York University, 1976.

Sehayik, Shaul. “Changes in the Status of Urban Jewish Women in Iraq at the End of the Nineteenth Century” (Hebrew). Pe’amim: Studies in the Cultural Heritage of Oriental Jewry 36 (1988): 64–88.

Shokeid, Moshe, and Shlomo Deshen. The Predicament of Homecoming: Culture and Social Life of North African Immigrants in Israel. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974.

Smooha, Sammy. Israel: Pluralism and Conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

Solomon, Neil. “Jewish Divorce Law and Contemporary Society.” The Jewish Journal of Sociology 25, no. 2 (1983):131–140 (Review).

Watson, Rubie S., and Patricia Buckley Ebrey. Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Yiftach, Yehezkel. The Righteous Woman from Babylon. Kfar Tabor: S. Gal’on, 1999.

Zenner, P. Walter. “Jews in Late Ottoman Syria: Community, Family and Religion.” In Jewish Societies in the Middle East: Community, Culture and Authority, edited by Shlomo Deshen and Walter P. Zenner, 187–210. Washington, D.C: University Press of America, 1982.