Hunter College

Hunter College of the City University of New York was founded in 1870 as a public, tuition-free secondary and teacher-training school for women that admitted students solely on the basis of academic merit, at a time when many institutions of higher education were implementing policies of selective admissions designed specifically to deflect disadvantaged students. As such, African American, Catholic, and Jewish women attended Hunter in disproportionate numbers, and Hunter’s student body differed significantly from that of other women’s colleges in America. Hunter educated scores of intellectually gifted and professionally talented women, including Nobel prize winners, politicians, authors, and pageant winners. In recent years, Hunter’s student population has continued to reflect the demographics of New York City, though it is now coeducational and charges tuition.

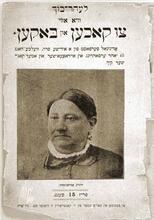

Long known as the “Jewish Girls’ Radcliffe,” Hunter College of the City University of New York was founded in 1870 as the Normal College of the City of New York. It was a public, tuition-free secondary and teacher-training school that admitted students solely on the basis of academic merit, determined by competitive examination, and by residency in the city. Over the years, it became a haven for academically advanced students unable to afford more costly schools or to gain admission to institutions with more restrictive admissions criteria. Women who were considered “socially undesirable”—African Americans, Catholics, and Jews, especially those from Eastern Europe—attended Hunter in disproportionate numbers. Hunter’s student body, therefore, differed significantly from that of other women’s colleges in America. From 1900 to the end of World War II, decades when many institutions of higher education implemented policies of selective admissions specifically designed to deflect minority students, Hunter gladly welcomed these same women. Hunter educated scores of intellectually gifted and professionally talented women whose skills and achievements amply repaid the city’s largesse.

The College’s founding: a welcoming start

With the founding of Hunter College as the female counterpart to all-male City College, New York City offered all of its citizens a system of public schools from kindergarten through college. For nearly a century, all students who resided in New York and who passed the highly competitive academic entrance examinations were assured a superb free education. An integral part of the public school system, the college used no selective criteria—social, financial or racial—other than competitive examination to determine admission.

The student body rapidly grew to reflect the ethnic composition of the city. Jewish students, as well as a small number of African Americans, attended from the beginning. Their steadily increasing numbers, claimed William Wood, president of the board of education, demonstrated that Jewish parents knew how to avail themselves of the magnificent training they had the right to obtain for their daughters.

Thus, in 1878, approximately two hundred of a total student body of 1,542 were Jewish. By 1889, fifty of three hundred graduates were Jewish, including the valedictorian. That year, Jewish students read four of six prize essays at commencement, won four of nine prizes, and received at least eighteen honorable mentions. The students of 1889 also unanimously selected a Jewish senior to deliver the address welcoming President Benjamin Harrison to New York City for the centennial of the Constitution.

Despite a nondenominational Christianity that pervaded the school in its early years, President Thomas Hunter ensured that the college respected the rights and feelings of all students. Hunter devised a system of discretionary absences to allow students to celebrate religious holidays without penalty and demanded that student societies and debating clubs exclude theological issues as topics of discussion or debate. He also insisted that competitive examinations remain in force as the only impartial, democratic means of determining admission to the college.

Early twentieth century: a symbol for the disadvantaged

Until the great immigration of the 1880s brought large numbers of Eastern European and Russian Jews to New York, Hunter’s Jewish students came primarily from old German and Spanish families. As the only public high school and eventually the only college for girls, the school attracted daughters of families able to spare their children’s contribution to the household economy. By the first decades of the new century, however, both Jewish and gentile middle-class families began to desert the public colleges in favor of private, selective schools. As these colleges began imposing selective admissions criteria based on ethnic and social factors, the free and nonselective public colleges of New York absorbed the highly intelligent but “socially undesirable” students unable to find acceptance elsewhere. Normal College, renamed Hunter College in 1914, and City College became the symbols of educational opportunity for generations of Jewish immigrants.

By the 1920s, Hunter’s students were overwhelmingly first-generation Americans: Although eighty percent of the students were American-born, only twenty-eight percent of their fathers had been born in the United States. Estimates of the number of Jewish women at Hunter range from forty percent of the student body in the 1920s to seventy-five percent in the 1930s when restrictive quotas at most private colleges and universities barred Jewish women from admission. The Depression effectively barred others, who could not afford the tuition of private colleges and universities. Hunter absorbed all who qualified and was soon the largest college for women in the world. Jewish life in the college flourished, and Jewish sororities and clubs, such as the Menorah Society, Avukah, and Hillel, proliferated. Students found both comfort and strength in belonging to a community of their own.

Jewish and Catholic student communities

Although immigrant families placed less emphasis on education for girls than for boys, Jewish parents generally supported their daughters’ desire to attend Hunter College and fostered their efforts to become teachers. Increasingly viewed as a means of upward social mobility, financial security, and intellectual gratification, teaching became the profession of choice for thousands of Jewish women. For many, Hunter provided the only choice of professional training: It was free, and its graduates dominated the eligibility lists for coveted teaching positions. Inevitably, as Jewish women graduated from Hunter in ever larger numbers, they came to dominate the ranks of New York’s teaching force and the city’s public schools.

Although a significant number of Hunter students through the 1960s were Jewish, most alumnae remember an equally large Catholic presence in the college. In recognition of this diversity, Hunter College acquired, through a special act of the New York State legislature, the Sara Delano Roosevelt Memorial House in 1940 for use as the first collegiate interfaith center. Traditionally, the president of the college was a Catholic and, acceding to the wishes of the church, the main campus on Park Avenue remained single-sex long after the heavily Jewish Bronx Campus—now Herbert H. Lehman College—became coeducational in 1951. Hunter College has had many Jewish acting presidents and subsidiary administrators but never a permanent Jewish president.

Hunter College today

In recent years, Hunter’s student population has continued to reflect the demographics of New York City. Now a senior college of the City University of New York, offering a vast array of undergraduate, graduate, and certificate programs, Hunter is coeducational, charges tuition, and attracts an extraordinarily diverse student body. After a decline in Jewish enrollments in the 1970s and 1980s, the college is again witnessing an upsurge as recent immigrants and refugees from the former Soviet bloc countries apply for admission. By becoming Hunter students, they are joining a long list of distinguished alumni, including Nobel Prize winners Rosalyn Sussman Yalow and Gertrude Belle Elion, author Bel Kaufman, politician Bella Abzug, consumer advocate and former Miss America Bess Myerson, and several presidents of Hadassah. These alumni demonstrate the tradition that placed Jewish students in the forefront of the drive for education.

Grunfeld, Katherina Kroo. “Purpose and Ambiguity: The Feminine World of Hunter College, 1869–1945.” Ed.D. diss., Teachers College, Columbia University (1991).

Hunter, Thomas. The Autobiography of Dr. Thomas Hunter. Edited by his daughters (1931).

Markowitz, Ruth Jacknow. “Subway Scholars at Concrete Campuses: Daughters of Jewish Immigrants Prepare for the Teaching Profession, New York City, 1920–1940.” History of Higher Education Annual 10 (1990): 31–50.

“The Normal College of New York City.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (April 1878): 680–682.

Patterson, Samuel White. Hunter College: Eighty-Five Years of Service (1955).

Shuster, George N. The Ground I Walked On: Reflections by the Former President of Hunter College (1961).

Synnott, Marcia Graham. The Half-Opened Door: Discrimination and Admissions at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, 1900–1970 (1979).

Wechsler, Harold S. The Qualified Student: A History of Selective College Admission in America (1977).