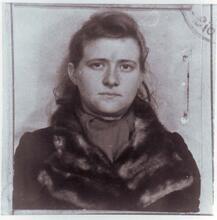

Anna Braude Heller

A brilliant pediatrician used to working in difficult circumstances, Anna Braude Heller struggled to keep children’s hospitals open through both World War I and World War II. Heller worked at the Berson and Bauman Children’s Hospital for Jewish children. When the hospital closed due to lack of funds during World War I, she helped raise money, and when it reopened in 1930 she became its chief physician and a member of its board. As war gripped Poland once again during World War II, the hospital was overrun with casualties, and when a bombing started a fire, Heller evacuated 100 children to nearby apartments and upheld standards of care despite the chaos and overcrowding. Although she evaded deportation in 1943, she was killed shortly afterwards when German soldiers raided the Warsaw Ghetto.

Early Life and Medical Training

Dr. Anna Braude Heller was born on January 6, 1888, in Warsaw to Aryeh Leib Broddo of Grodno and Tauba Litwin of Bialystok. She was the oldest of four daughters. Her father was a well-to-do merchant, and her mother assisted him. Heller was raised in an open, traditional household. Her father was religiously observant but very liberal in his outlook. The parents spoke Yiddish between themselves and Polish with their children. Heller was an excellent student, highly independent in her opinions, with special sensitivity to the needs of others.

She received her elementary education at the popular girls school in Warsaw run by Fryderyda Thlegrue. After completing the sixth grade she continued her studies privately and in the spring of 1906 successfully passed her matriculation examinations. In autumn of that year she traveled to Geneva to study at the Faculty of Social Sciences, but soon moved to Zurich and began to study medicine. Towards the end of her studies she moved to Berlin and in 1912 completed her medical studies there. Heller decided to specialize in pediatric medicine and moved to Russia after completing her residency in order to obtain her medical license in St. Petersburg. The licensing examinations were particularly difficult for her since she did not receive permission to stay in the city for the entire four-week testing period. (Jews were prohibited from remaining outside the Pale of Settlement unless they had a special permit.) As a result, she was forced to reside in the city illegally and change her place of lodging every night.

For the first year after receiving her medical license Heller worked as a physician in Russian villages. She then embarked on her professional career in earnest, establishing the Włodzimierz Medem Children’s Sanatorium in Otwock and also serving as a physician for the Central Yiddish School Organization (CYShO), affiliated with the Bund organization. While still in Geneva Dr. Heller had encountered socialist circles that shared her interest in social justice and had become a member of the Bund. She identified deeply with the Jewish people, while she also had patriotic feelings for Poland.

Return to Warsaw

In 1913 she returned to Warsaw, where she began working at the Jewish hospital on Czysta Street in the departments of internal medicine and neurology. Shortly before the outbreak of World War I she found work at the Berson and Bauman Children’s Hospital, which had just come into existence. The hospital had been established with funds donated by the Bersons, an assimilated Jewish family of merchants; when the donation proved insufficient to complete construction, the daughter Paulina Berson Bauman donated the remainder. The hospital opened its doors in 1915 with only twenty-four beds, but within a short time it expanded to one hundred beds. Over the years, additional donors enabled the hospital to add various new wings, which bore their names.

The hospital set high standards for the care of children, stressing the need to differentiate between the treatment of children and adults. From the outset, it saw its mission as taking care of Jewish children, as distinct from the Jewish community as a whole. Already during World War I, the hospital had to shut down due to lack of funds.

In 1916 Dr. Anna Braude married Eliezer Heller (1885–1954), an engineer, and was forced to leave the hospital. The couple had two sons, the elder named Ari Leon, and the younger Olum.

Despite her marriage and the birth of her children, Heller did not abandon her profession. She worked at a number of clinics in the city and played an active role in the founding of the Children’s Friends Society (Towarzystowo Przyjaciol Dzieci) in 1916; among its objectives was the reopening of the Children’s Hospital, which was Heller’s dream. She was a central figure in the Society, working in the clinics under its aegis and in well-baby clinics. She also promoted the development of social work aimed at children and of psychological treatment at a special counseling clinic that the Society helped to establish.

During the 1920s Heller visited children’s hospitals in several European countries and came back determined to obtain the funding needed to reopen the Berson-Bauman Hospital. Even after the Joint Distribution Committee responded to her appeals, allocating money to renovate the building and reestablish the hospital, Heller persisted in her efforts to secure additional funds.

In 1930 the hospital reopened. It was considered the most advanced children’s hospital in Poland. Heller, who was already a senior pediatrician known and respected throughout Poland, was appointed chief physician of the hospital and made a member of the board of directors. Praising the accuracy of her diagnoses and her medical intuition, a colleague remarked: “Like an artist blessed with divine gifts, she is blessed with a God-given talent as a physician.” After years of toil, with meager resources, the hospital’s financial situation began to improve, with health funds paying to have children treated at the hospital.

In the years between the world wars a number of tragedies took place in Heller’s personal life: her younger son, Olum, died in 1926, and her husband died of surgical complications in 1934 at the age of forty-nine. Heller devoted her life to the hospital and to the treatment of children, but she could not escape the pain of the deaths of her young son and husband.

World War II

Upon the outbreak of World War II the hospital found itself on the “front lines” in the struggle to remove and treat the city’s wounded. Adults were sent there, since other hospitals in the city had been damaged by bombings. Heller moved into the hospital, working day and night to treat children and adults. When a fire broke out in one of the wings as the result of a bombing, Heller, with the aid of her staff, transferred some one hundred children to a private apartment whose owners were willing to take them in.

With the entry of the Germans into the city, conditions at the hospital worsened. It was forbidden to treat non-Jewish patients and the health funds were ordered by the German authorities to cease their support entirely. The hospital became dependent for its day-to-day operations on the community, the Jewish self-help institutions and the donations of individuals.

The establishment of the ghetto further intensified the crisis, despite the fact that the hospital was located on the boundary of the ghetto and was able to retain the use of its building. Harsh living conditions and lack of sanitation in the ghetto, and especially the severe hunger afflicting most of the inhabitants, led to epidemics of typhus and various children’s diseases. Scores of children came to the hospital, wounded by gunshots or blows from German and Polish soldiers and policemen. Children were injured in accidents in homes and courtyards and particularly in attempts to pass to the Aryan side to smuggle food and the like into the ghetto. The hospital was receiving growing numbers of patients and there was insufficient space to house them all. Scant resources made proper treatment impossible. Mortality rates were high, despite the devotion displayed by the medical personnel and support staff.

Heller saw the hospital as her home. She continued to uphold proper medical standards, expecting the hospital staff to maintain the usual routine of medical tests, twice-daily doctors’ rounds, individual reports on patients and meticulous record-keeping. She also insisted on neat and clean attire for the staff and was strict about the cleanliness of the hospital itself. This was a particularly difficult task given the overcrowded conditions, the need to place several children in one bed, the lack of undergarments and the weakness of the children, who often could not control their bodily functions.

Her strict approach to the hospital’s work ethic and medical standards; her personal familiarity with, and interest in, each child; and her daily consultations with medical personnel, all fostered an atmosphere of superhuman effort and dedication. The admiration felt toward Heller herself was boundless.

Heller, who was also a member of the Health Council established by the Judenrat and of the Health Department, took part in medical studies conducted in the ghetto, primarily relating to the influence of starvation on the body and the resultant physical changes. Her colleagues spoke of her professionalism, her academic approach and her great devotion.

When the mass deportations from the Ghetto began in July 1942, Heller attempted to block the deportation of children from the hospital. After the area of the ghetto was constricted, the hospital relocated and conditions deteriorated further. Many of the hospital’s workers were sent to Treblinka and Heller was forced to choose a group of workers whom the Germans permitted to remain in the Ghetto. This was a morally impossible task.

In the autumn of 1942, and again in the winter of 1943, Heller was urged by friends inside and outside the Ghetto to escape to the Aryan side. She refused. She did, however, help her older son, who was also a doctor, and members of his family to get to the Aryan side. Her sister Juditha also made her way to the Aryan side, but Heller herself saw her place in the Ghetto alongside the adults and children whom she had taken care of for so many years. Together with her sister, Dr. Roza Aftergut, whose husband and daughter had been sent to Treblinka in the mass deportation, Dr. Anna Braude Heller remained behind in the Ghetto and perished there. It is not known precisely how she died—whether she burned to death in the bunker where she hid with her sister and friends, or was murdered by the Germans when she emerged from the burning shelter.

Blady Szwajer, Adina. I Remember Nothing More: The Warsaw Children’s Hospital and the Jewish Resistance. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990.

Roland, Charles G. Courage Under Siege: Starvation, Disease and Death in the Warsaw Ghetto. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Yad Vashem Archives. Testimony of Juditha Braude. File 03/2360.