College Students in the United States

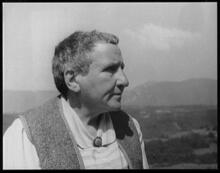

Hillel offered "Jewish experiences" and an introduction to their heritage to all Jewish college students, regardless of their denominational background. Pictured here are students at Hillel's "Model Seder" at the University of Maryland in 1948.

Institution: Hillel: The Foundation for Jewish Campus Life.

In the 1920s, Jewish women participated in a wave of expanding collegiate enrollment, joining in greater numbers and with increased visibility. However, subtle sexism and antisemitism in college administrations made it difficult for Jewish female applicants to become admitted to certain institutions. By the early 1970s, Jewish women began to surpass their non-Jewish counterparts in terms of the percentage of females compared to males of the same religious faith, and by the late 1990s, the number of Jewish women receiving a collegiate education had reached a greater degree of parity with Jewish men. The striking contrast in experiences between the first years of the twentieth and the twenty-first centuries demonstrates that Jewish women have succeeded in establishing a place for themselves on college campuses.

While Jews have traditionally placed a great deal of emphasis on education and learning, in the past they reserved the privilege of education primarily for their sons. Religious and cultural ideals assigning women’s place to the home and family combined with societal sexism and antisemitism to make the course charted by Jewish women in pursuit of a college education rocky and in many cases inaccessible. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, Jewish women in America achieved parity with their male counterparts on college campuses, but only after many decades of struggle. Indeed, the obstacles facing all American women who sought to enroll in college institutions in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century proved numerous, imposing, and at times, defeating. While antisemitism posed an added challenge that Jewish women had to conquer in order to receive the college education they sought in the first half of the twentieth century, they steadily achieved admission and acceptance after the postwar period and into the twenty first century.

The Beginnings of Female College Education

The mass immigration of Jews to the United States between 1881 and 1924 occurred at precisely the same time as the development of public education for the masses, but Jewish males reaped the benefits of this educational movement in far greater numbers than did their Jewish sisters. While recent arrivals to the country sought to enhance their sons’ chances of success in America by sending them to school and then to college, the same did not apply to daughters, whose chances of earning a living even with a college education appeared slight. Indeed, for most parents, the help provided by daughters within the household and the wages secured from outside work represented important contributions to the family in terms of putting food on the table and even paying the tuition required by their brothers’ schools. Parents were not willing to forgo this financial and physical assistance by supporting their daughters’ quest for a college education.

This parental preference for sending sons to school while keeping daughters home was common to all religious groups, not just to Jews. In fact, although more Jewish males than females attended school in the early 1900s, Jewish women were more likely to receive an education than any other group of women in the Unites States. Jewish daughters often pursued an education while holding down jobs and helping with family chores. A study of night school attendees in 1910 revealed that although Jews comprised only nineteen percent of the population in New York City, forty percent of the women enrolled in night school were Jewish. Still, this high number of women willing to pursue an education, even after a long day of work, did not translate into a significant Jewish female presence in college during the decades preceding and following the beginning of the twentieth century.

In the 1870s and 1880s, less than two percent of women aged eighteen to twenty-one attended college. Strongly held societal beliefs that assigned woman’s proper place to the home served as prescriptions against higher education for women. Of the small group of pioneers who did enroll in college, nearly all came from Protestant backgrounds. The few women who might have been Jewish either hid their religious identities or else blended in with their fellow collegians and thus escaped comment and notice on the basis of their religion. Amelia D. Alpiner, a student in the class of 1896 at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, was the first Jewish female collegian to be identified according to her religion. A prominent student on campus, Alpinger played a visible role in many campus activities and served as a charter member of Pi Beta Phi sorority. Two years after she graduated, another identifiable Jewish female, Gertrude Stein, graduated from the Harvard Annex, later Radcliffe College, the women’s division of Harvard.

Other than these two prominent women, the Jewish females who attended college during the latter decades of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth century did so in relative anonymity. Hunter College, the women’s college of the City University of New York (then called the Normal College of the City University of New York), was an exception. A public teacher-training institution that admitted students strictly on the basis of academic merit, Hunter College had 200 Jewish students out of a total of 1,542 students in 1878, and 50 Jews out of 300 graduates (including the valedictorian) by 1889.

Because of their small numbers and relative invisibility as a group, Jewish students, and particularly the females among them, attracted little notice in terms of their religion from either their fellow students or outside society. Jewish members of the community, however, at times helped the few Jewish collegians to maintain their religious identities by inviting them to Passover Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seders and to share other celebrations with them. In some places, members of the Jewish Ladies Circle or other social organizations in the community helped Jewish students to take on their new collegiate identities without losing their sense of themselves as Jews. In other places, young Jewish women struggled alone to make their way through the intricacies of higher education, often finding it easier to forgo or suppress their Jewish identity to fit in better with the small number of female collegians surrounding them.

Although the number of Jewish women enrolled in colleges increased, according to the responses to a questionnaire distributed to colleges across the United States in June 1916 by the Intercollegiate Menorah Association, Jewish women comprised only a tiny fraction of the college population. The survey also found that Jewish men attended college in a higher proportion than did their non-Jewish counterparts, while female Jews comprised only one-ninth the number of male Jews and attended college in numbers less than half of their non-Jewish female counterparts. While the study located only a tiny number of Jewish women enrolled at colleges nationwide, it found that at the all-women’s colleges of the Northeast, such as Barnard, Radcliffe, Smith, Wellesley, Vassar, and Bryn Mawr, 335 Jewish women held five percent of the enrolled places.

Having few Jewish sisters accompanying them in their collegiate quests both harmed and aided Jewish women in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century. While often spared the outright antisemitism directed at male Jews, Jewish women tended to face their struggles alone and had to combat more tacit forms of antisemitism. According to the Intercollegiate Menorah Association survey, while Jewish women participated along with other students in all branches of collegiate activities, many of them did so by hiding or simply not declaring their religious and cultural heritage.

By all accounts, these early Jewish female collegians performed well in their studies. In 1916, at Smith College, where Jews comprised only three percent of the student body, they won nine percent of the Phi Beta Kappa keys awarded. In the same year, at Bryn Mawr College, although Jewish women represented only four percent of the senior class, they earned more than twice that percentage of the cum laude degrees awarded. In addition to earning notable marks, the early Jewish female collegians also took steps upon graduation to put their education to use. From 1914 to 1915, for example, 5.5 percent of the women registered at the Intercollegiate Bureau of Occupations were Jews, although Jewish women comprised a far smaller percentage of the female college population.

The Beginnings of Female College Education

The wave of immigration that accompanied the spread of mass education served to increase the Jewish population in the United States more than threefold. Between 1897 and 1917, the number of Jews in the country expanded from less than one million to more than 3.3 million, and the bulk of the new arrivals hailed from Eastern Europe. These new arrivals proved poorer, less educated, and less cultivated than their better-assimilated German predecessors. When the children of these recent immigrants began to arrive in numbers on college campuses in the late 1910s and 1920s, their presence attracted greater societal and institutional notice and comment than had the earlier Jewish students.

The 1920s has been called a period of democratization in higher education, a time when the ivy gates opened en masse to students of less privileged and more racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds. Jewish women participated in this wave of expanding enrollment, joining the collegiate ranks in greater numbers and with increased visibility. By 1914, enough Jewish women attended Radcliffe College to form a Menorah Society, whose mission included spreading Jewish culture and ideas. Increasingly made aware by their fellow students and institutions of their identities as Jews, Jewish female students, buoyed by their strength in numbers, began to form organizations to aid themselves and their Jewish sisters in responding to and combating the rise in antisemitism and discrimination that accompanied their increased presence on campus.

Concurrent societal paranoia and fear of foreigners mixed with institutional concerns regarding the expanding number of Jewish students enrolled on campus to produce a wave of antisemitism that reached high proportions during the 1920s and 1930s. During these two decades and extending into the 1950s, students, alumni, and administrators of many institutions, eager to preserve the so-called Anglo-Saxon superiority of their colleges, instituted explicit and tacit policies both to limit Jewish enrollment and to restrict Jewish participation in campus activities.

Drawing upon popular “scientific” racial theories to justify their discriminatory policies, administrators of many institutions of higher education across the country created screening techniques to weed out Jewish applicants for admission. These institutional efforts to maintain an exclusive and “homogeneous” student body hurt Jews more than they did other ethnic and religious groups. Whereas Catholics and African Americans developed and maintained colleges specifically for their own students, Jews created few institutions of their own, preferring instead to enter the American mainstream through the same avenues as non-Jews.

In the 1920s and 1930s, prominent institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia established admissions quotas and other practices for manipulating admission procedures to curb or even prevent the entry of Jewish students. Jewish women felt the ramifications of these policies when the Ivy “sister” schools, such as Barnard and Radcliffe, and the all-female institutions of many other schools began to copy the more prestigious institutions with their anti-Jewish stances. Indeed, while technically forbidden by state and national laws from imposing admission quotas based on race, religion, or ethnicity, the women’s branches of many major state universities in the eastern and midwestern United States devised strategies to address a situation they labeled the “Jewish problem” by limiting, in a tacit manner, Jewish attendance at their institutions. Mirroring these developments, the estimated number of Jewish students at Hunter College jumped from forty percent of the student body in the 1920s to seventy-five percent in the 1930s, reflecting a continued “open-door” policy towards immigrants and minorities that contrasted with the attitudes then prevalent on university campuses.

Prompted by concerns that a large Jewish attendance would make their institutions less attractive to the sought-after white Anglo-Saxon Protestant students, schools such as New Jersey College, the female coordinate of Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, created a department of admissions whose representative would evaluate the personal background, leadership, breadth, and potential of prospective students. Ranking students by applying a set of subjective criteria enabled college administrators to weed out Jewish applicants who generally came with higher marks and scores than their non-Jewish counterparts, but who nevertheless were considered inferior enrollment material.

The explicit and more subtle discriminatory policies against Jewish female applicants proved effective. Between 1928 and 1932, for example, while the number of Jews in the northern New Jersey area increased dramatically and the number of Jewish students enrolled at Rutgers University more than doubled, the Jewish female enrollment at New Jersey College declined by more than a third, from seventeen percent in 1928 to eleven percent in 1932. In 1930, moreover, while New Jersey College accepted 337 of the 635 females who applied, an acceptance rate of sixty-one percent, the admissions committee issued acceptances to only fifty of the 162 Jewish applicants, at a rate of thirty-one percent, despite the fact that the chair of the Committee on Admission and Freshman Work reported of the Jewish applicants that “their scholastic standing is usually better than that of other students” (Greenberg and Zenchelsky, 304). Harvard’s sister school, Radcliffe College, joined New Jersey College in introducing screening policies to weed out Jewish candidates from admissions. Between 1936 and 1938, the women’s college reduced the number of Jewish women it admitted by almost half, and cut the percentage of Jewish students enrolled among its ranks from 24.8 to 16.5, despite the fact that applications for admissions from Jewish women rose during the same period.

At New Jersey College, Radcliffe and other institutions, deans of women and other powerful administrators adopted the practice of interviewing every student who applied and evaluating each on the basis of intellectual ability, character, personality, health and background. This practice enabled administrators to single out for rejection the students whom they considered “undesirable,” “crude” and “lacking in refinement,” a high proportion of whom were often Jewish. When Jewish groups publicly pressured institutions to ease their restrictions, the schools under examination simply altered their processes of selection and placed limits on the number of commuter students they would admit. This policy proved an effective, if more subtle, approach to curbing Jewish admissions, as in the late 1920s and 1930s, a high proportion of Jewish women students commuted to their respective campuses.

In fact, a majority of the Jewish women arriving on campus between the two world wars did so on a daily basis. Preferring to keep their daughters close to home in the hopes of both saving money and keeping an eye on their female offspring, Jewish families played a major role in swelling the ranks of the commuter student population in schools located in New York and Boston. By 1934, Jews accounted for more than fifty percent of the New York female college student population. Although Jewish males felt subtly stigmatized by their peers for attending local institutions, their sisters found that attending schools like New York University and City College of New York, as commuters, represented a high achievement and brought them prestige within the young Jewish community.

Both the commuter students and their counterparts at distant colleges felt the dual sting of sexism and antisemitism from institutions unaccustomed to the visible presence of Jewish female collegians. Attending schools resistant to their presence proved difficult and at times lonely for women trying to earn a higher education. Indeed, the pressure to conform to collegiate ideals despite their religious differences and the desire to blend into campus environments suspicious of, or even hostile to, their presence created numerous crises of identity for Jewish women and other members of minority groups. Hounded by the knowledge that in order to fit in they had to hide their religious affiliation, yet conscious that such action would separate them from their own families and communities, Jewish female students struggled to find a way to make themselves belong on American college campuses in the early decades of the century.

The Jewish Greek system, sororities and fraternities, founded at the same time as Jewish students began to flock to universities, sought to aid the new collegians in their quest to belong. For many Jewish females, the religious-based sororities, created and developed by sisters of their faith in the 1910s, provided opportunities for campus involvement that might have otherwise been closed to them. The Jewish organizations served as an entrée into mainstream collegiate society, in part through the organizations’ deliberate, collective mission to counter negative Jewish stereotypes. Teaching etiquette, manners, dress, sports, and upper-middle-class activities and mores, Jewish sororities and fraternities strove to make their members ideal representatives of American college students. Only through their Greek letter societies, Jewish sorority women argued, could they as Jews reach parity on campus with their non-Jewish counterparts. By placing a high level of emphasis on school loyalty and patriotism and on dispelling myths about Jews by their own deportment and behavior, the members of the Jewish Greek system sought to use their organizations as vehicles for personal as well as collective advancement.

The Jewish sororities attracted a high percentage of the female Jewish college population. A 1927 survey published by the American Jewish Yearbook found that fraternity and sorority membership made up eighty percent of membership in all Jewish student organizations and was composed of twenty-five thousand Jewish students. Yet, while these organizations drew many Jewish women into their ranks, the sororities restricted their membership to a chosen group of students. For those excluded from membership, the Jewish sororities served to exacerbate feelings of exclusion and discrimination—a sentiment that Hillel, a Jewish society formed at the University of Illinois in the 1920s, sought to alleviate. Created by a newly ordained rabbi to provide support for a Jewish student population lacking in direction and faith, Hillel sought to provide students with a religious, moral, and social outlet through an organization in which they could learn the principles of Judaism while cultivating themselves as individuals. In response to the selective Greek letter societies, Hillel opened itself to all Jewish students, embracing all brands of the faith without exclusion.

Increasing Numbers, Increasing Struggles

Hillel offered "Jewish experiences" and an introduction to their heritage to all Jewish college students, regardless of their denominational background. Pictured here are students at Hillel's "Model Seder" at the University of Maryland in 1948.

Institution: Hillel: The Foundation for Jewish Campus Life.

The wave of immigration that accompanied the spread of mass education served to increase the Jewish population in the United States more than threefold. Between 1897 and 1917, the number of Jews in the country expanded from less than one million to more than 3.3 million, and the bulk of the new arrivals hailed from Eastern Europe. These new arrivals proved poorer, less educated, and less cultivated than their better-assimilated German predecessors. When the children of these recent immigrants began to arrive in numbers on college campuses in the late 1910s and 1920s, their presence attracted greater societal and institutional notice and comment than had the earlier Jewish students.

The 1920s has been called a period of democratization in higher education, a time when the ivy gates opened en masse to students of less privileged and more racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds. Jewish women participated in this wave of expanding enrollment, joining the collegiate ranks in greater numbers and with increased visibility. By 1914, enough Jewish women attended Radcliffe College to form a Menorah Society, whose mission included spreading Jewish culture and ideas. Increasingly made aware by their fellow students and institutions of their identities as Jews, Jewish female students, buoyed by their strength in numbers, began to form organizations to aid themselves and their Jewish sisters in responding to and combating the rise in antisemitism and discrimination that accompanied their increased presence on campus.

Concurrent societal paranoia and fear of foreigners mixed with institutional concerns regarding the expanding number of Jewish students enrolled on campus to produce a wave of antisemitism that reached high proportions during the 1920s and 1930s. During these two decades and extending into the 1950s, students, alumni, and administrators of many institutions, eager to preserve the so-called Anglo-Saxon superiority of their colleges, instituted explicit and tacit policies both to limit Jewish enrollment and to restrict Jewish participation in campus activities.

Drawing upon popular “scientific” racial theories to justify their discriminatory policies, administrators of many institutions of higher education across the country created screening techniques to weed out Jewish applicants for admission. These institutional efforts to maintain an exclusive and “homogeneous” student body hurt Jews more than they did other ethnic and religious groups. Whereas Catholics and African Americans developed and maintained colleges specifically for their own students, Jews created few institutions of their own, preferring instead to enter the American mainstream through the same avenues as non-Jews.

In the 1920s and 1930s, prominent institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia established admissions quotas and other practices for manipulating admission procedures to curb or even prevent the entry of Jewish students. Jewish women felt the ramifications of these policies when the Ivy “sister” schools, such as Barnard and Radcliffe, and the all-female institutions of many other schools began to copy the more prestigious institutions with their anti-Jewish stances. Indeed, while technically forbidden by state and national laws from imposing admission quotas based on race, religion, or ethnicity, the women’s branches of many major state universities in the eastern and midwestern United States devised strategies to address a situation they labeled the “Jewish problem” by limiting, in a subtle manner, Jewish attendance at their institutions. Mirroring these developments, the estimated number of Jewish students at Hunter College jumped from forty percent of the student body in the 1920s to seventy-five percent in the 1930s, reflecting a continued “open-door” policy towards immigrants and minorities that contrasted with the attitudes then prevalent on university campuses.

Prompted by concerns that a large Jewish attendance would make their institutions less attractive to the sought-after white Anglo-Saxon Protestant students, schools such as New Jersey College (the female coordinate of Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey) created a department of admissions whose representative would evaluate the personal background, leadership, breadth, and potential of prospective students. Ranking students by applying a set of subjective criteria enabled college administrators to weed out Jewish applicants who generally came with higher marks and scores than their non-Jewish counterparts but who nevertheless were considered inferior enrollment material.

The explicit and more subtle discriminatory policies against Jewish female applicants proved effective. Between 1928 and 1932, for example, while the number of Jews in the northern New Jersey area increased dramatically and the number of Jewish students enrolled at Rutgers University more than doubled, the Jewish female enrollment at New Jersey College declined by more than a third, from seventeen percent in 1928 to eleven percent in 1932. In 1930, moreover, while New Jersey College accepted 337 of the 635 females who applied, an acceptance rate of fifty-three percent, the admissions committee issued acceptances to only fifty of the 162 Jewish applicants, at a rate of thirty-one percent, despite the fact that the chair of the Committee on Admission and Freshman Work reported of the Jewish applicants that “their scholastic standing is usually better than that of other students” (Greenberg and Zenchelsky, 304). Harvard’s sister school, Radcliffe College, joined New Jersey College in introducing screening policies to weed out Jewish candidates for admissions. Between 1936 and 1938, the women’s college reduced the number of Jewish women it admitted by almost half and cut the percentage of Jewish students enrolled among its ranks from 24.8 to 16.5, despite the fact that applications for admissions from Jewish women rose during the same period.

At New Jersey College, Radcliffe, and other institutions, deans of women and other powerful administrators adopted the practice of interviewing every student who applied and evaluating each on the basis of intellectual ability, character, personality, health, and background. This practice enabled administrators to single out for rejection the students whom they considered “undesirable,” “crude,” and “lacking in refinement,” a high proportion of whom were often Jewish. When Jewish groups publicly pressured institutions to ease their restrictions, the schools under examination simply altered their processes of selection and placed limits on the number of commuter students they would admit. This policy proved an effective, if more subtle, approach to curbing Jewish admissions, as in the late 1920s and 1930s a high proportion of Jewish women students commuted to their respective campuses.

In fact, a majority of the Jewish women arriving on campus between the two World Wars did so on a daily basis. Preferring to keep their daughters close to home in the hopes of both saving money and keeping an eye on their female offspring, Jewish families played a major role in swelling the ranks of the commuter student population in schools located in New York and Boston. As “subway scholars” at Hunter College, Ruth Jacknow Markowitz concludes that Jewish women comprised roughly 70 percent of the teaching training institute between 1920 and 1940.

By 1934, Jews accounted for more than fifty percent of the New York female college student population. Although Jewish males felt subtly stigmatized by their peers for attending local institutions, their sisters found that attending schools like New York University and City College of New York, as commuters, represented a high achievement and brought them prestige within the young Jewish community.

Both the commuter students and their counterparts at distant colleges felt the dual sting of sexism and antisemitism from institutions unaccustomed to the visible presence of Jewish female collegians. Attending schools resistant to their presence proved difficult and at times lonely for women trying to earn a higher education. Indeed, the pressure to conform to collegiate ideals despite their religious differences and the desire to blend into campus environments suspicious of, or even hostile to, their presence created numerous crises of identity for Jewish women and other members of minority groups. Hounded by the knowledge that in order to fit in they had to hide their religious affiliation, yet conscious that such action would separate them from their own families and communities, Jewish female students struggled to find a way to make themselves belong on American college campuses in the early decades of the century.

The Jewish Greek system, sororities and fraternities, founded at the same time as Jewish students began to flock to universities, sought to aid the new collegians in their quest to belong. For many Jewish females, the religious-based sororities, created and developed by sisters of their faith in the 1910s, provided opportunities for campus involvement that might have otherwise been closed to them. The Jewish organizations served as an entrée into mainstream collegiate society, in part through the organizations’ deliberate, collective mission to counter negative Jewish stereotypes. Teaching etiquette, manners, dress, sports, and upper-middle-class activities and mores, Jewish sororities and fraternities strove to make their members ideal representatives of American college students. Only through their Greek letter societies, Jewish sorority women argued, could they as Jews reach parity on campus with their non-Jewish counterparts. By placing a high level of emphasis on school loyalty and patriotism and on dispelling myths about Jews by their own deportment and behavior, the members of the Jewish Greek system sought to use their organizations as vehicles for personal as well as collective advancement.

The Jewish sororities attracted a high percentage of the female Jewish college population. A 1927 survey published by the American Jewish Yearbook found that fraternity and sorority membership made up eighty percent of membership in all Jewish student organizations and was composed of 25,000 Jewish students. Yet, while these organizations drew many Jewish women into their ranks, the sororities restricted their membership to a chosen group of students. For those excluded from membership, the Jewish sororities served to exacerbate feelings of exclusion and discrimination—a sentiment that Hillel, a Jewish society formed at the University of Illinois in the 1920s, sought to alleviate. Created by a newly ordained rabbi to provide support for a Jewish student population lacking in direction and faith, Hillel sought to provide students with a religious, moral, and social outlet through an organization in which they could learn the principles of Judaism while cultivating themselves as individuals. In response to the selective Greek letter societies, Hillel opened itself to all Jewish students, embracing all brands of the faith without exclusion.

Hillel remained small at first, as the members of the highly developed Jewish Greek system treated the new organization with skepticism for its public assertion of Judaism. Used to hiding or at least downplaying their religion, the Jewish Greeks argued that the activist stance adopted by Hillel would make their own mission of assimilation more difficult. However, as discrimination on the part of the prestigious eastern schools caused increasing numbers of Jewish students to flock to campuses in the South and Midwest, Hillel soon spread to other institutions. By 1927, it boasted branches at Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio State, Michigan, California, Cornell, West Virginia, and Texas, with requests from other institutions pouring in.

The Activist 1930s and the War

Jewish students played active and important roles in the student protest movement of the 1930s. In high numbers, they joined the newly developing peace and protest organizations. The American Student Union, the most prominent campus protest group of the time, thrived mainly on campuses populated by large numbers of Jewish students. Female Jews adopted a more political stance on campus than ever before. At Radcliffe, for example, they abandoned en masse their social organizations like the Menorah Club and dedicated their time and efforts instead to the more politically activist Avukah group.

The association of Jewish students with the protest movement served to increase displays of public antisemitism in college towns. Outraged citizens responded to what they perceived as the movement’s socialist and communist leanings by charging the student members—and particularly the Jews among them—with anti-American tendencies. The rise of Nazism in Europe added to the pressures placed on Jewish collegians. Should they downplay their Judaism and thus escape the blame of those who said that the Jewish people had brought their hardships on themselves? Should they abandon the peace movement and turn their energies instead to opposing Nazism and supporting Hitler’s foes? Regardless of which course they chose to follow, Jewish students in the 1930s pursued their college degrees cognizant of the additional weight added to their shoulders by virtue of their religion.

Within the Jewish Greek system, the issue of what members should do in response to Nazism and the increase in antisemitic expression on the part of the American public prompted a great deal of discussion. Fiercely patriotic since their inception and wary of affiliating themselves too strongly with radical causes, Jewish sorority and fraternity leaders warned their sisters and brothers that all Jews would be judged by the members’ behavior. Shying away from political action for fear of drawing public criticism, the Jewish Greek organizations chose instead to aid the Jewish cause by serving as “model” representatives of their faith. As Alpha Epsilon Phi national president Reba B. Cohen reminded her sorority sisters in 1939, “We can, as college women, best serve our people by creating better understanding between Jews and non-Jews, by paying special attention to our dress, manners, and speech, and by cooperating amongst ourselves” (Sanua, 17).

When America joined its European allies and entered the war in 1941, Jewish collegians rushed to join the cause. Although during the war years women outnumbered men on campus, the air of abnormality created by an absence of males who had previously dominated the campuses reminded female students of the temporary nature of this situation. Watching their male friends and brothers join the armed forces, Jewish female collegians turned their efforts to doing their part to help the American cause.

Domesticity in the 1950s

As the veterans flocked to American colleges after World War II, Jewish and non-Jewish women became a smaller percentage of the college population than they had been either prior to or during the war. The number of female collegians increased in real numbers, from 601,000 in 1940 to 806,000 in 1950, but the percentage of female students declined, from 40.2 percent in 1940 to only 30.2 percent of all students in 1950. For Jewish women collegians in the aftermath of the war, sex as much as religion played a decisive role in shaping their college experiences.

Like non-Jewish women, the Jewish female collegians of the 1950s celebrated domesticity, beauty, and traditionally “womanly” concerns such as marriage and family. A B’nai B’rith survey of female college graduates, conducted from 1946 to 1959, found that female graduates of the period married young, often quitting school in the process, and bore children at an earlier age than had their mothers. The survey also found that Jewish women led this return to domesticity, marrying more quickly after graduation than their non-Jewish cohorts, although they waited longer than non-Jews to bear children.

The courses of study that colleges offered to female students in the 1950s both mirrored and shaped the revival of domesticity so celebrated by the American media at this time. Crowded out of the traditional liberal arts classrooms by male students eager to enter the corporate world of postwar America, high numbers of female students of all religions turned to “womanly” subjects such as health and education. In their choice of majors, however, Jewish women differed from other students. While non-Jewish women chose to major in disciplines like English and history, which would prepare them for teaching careers, and business administration and secretarial training in preparation for work as secretaries, Jewish women shied away from these subjects and majored instead in psychology, the social sciences, government and public administration, economics, and languages, in preparation for careers in health-related services and in the professions. Although many Jewish women, like all female graduates, adhered to the public celebrations of domesticity by passing over careers of their own to serve as homemakers and full-time mothers, they still pursued majors in areas where they, as Jews, would be likely to find jobs.

Although in their choices of majors Jewish women set themselves off from their non-Jewish counterparts, the importance of religion as a determinant of college experience declined in relative terms during the postwar years. While laws such as the 1948 Fair Education Practices Act in New York and, later, Title IV of the 1964 Civil Rights Act called for an end to discrimination on the basis of race, creed, color, or national origin, more tangible pressures also worked to break down religious divisions on college campuses.

In the early 1950s, the Jewish sororities, and eventually the fraternities, succumbed to this pressure and dropped their religious affiliation. With their Jewish identity now historical rather than functional, the formerly Jewish sororities also removed the religious overtones from their celebrations and rituals. Now reluctant to take part in any Jewish activities for fear of being accused of sectarianism, Jewish sorority women shied away from Hillel and other explicitly faith-oriented groups. As a result of the removal of the sectarian clauses, the degree to which religion played a role in shaping the campus experiences of Jewish female collegians declined. At the same time, however, religious affiliation still played an important role in determining which students would be allowed to enroll in particular institutions of higher learning.

Despite state laws and governmental pressure, college institutions continued to impose quotas on Jewish enrollment in the years following the war. A 1950 study of seventy-six nonsectarian colleges in upstate New York revealed that nearly one-third of the schools still placed restrictions on the numbers of Jews and other minorities admitted, some in the form of quotas, others in outright rejection.

In spite of the obstacles they faced in winning admissions to certain institutions of higher learning, Jewish women continued to push for a college education. Indeed, Jewish students of both sexes flocked to campus during the 1950s, despite quotas. By 1960, sixty-three percent of Jewish men and women aged eighteen though twenty-four attended college. Despite the postwar decline in the percentage of females enrolled in institutions of higher education, the number of Jewish women matriculating continued to rise. By the mid-1960s, their numbers crept close to the figures for Jewish male attendance and for non-Jewish female attendance.

Rising Consciousness: Jewish Female Identity in the 1960s and 1970s

During the late 1960s, female collegians for the first time reached a level of parity with the number of men enrolled on college campuses across the United States. The 1972 passage of Title IX of the Educational Amendments Act added the weight of law to the equality of opportunity that college women had struggled so hard to achieve. For Jewish women, the heightened social, sexual, and ethnic consciousness on campus brought about by the student protest movements of the 1960s created a campus environment more favorable to their presence than had existed at any point in the century.

The civil rights movement and ensuing campus protests attracted Jewish students to their causes in high numbers. In fact, at a time when Jews comprised only three percent of the United States population and ten percent of the college population, they served in the majority of leadership roles within the student protest organizations and made up between thirty-three and forty percent of the active membership of the movement. Although Jewish women took less prominent roles than their brothers in the civil rights and protest movements, female collegiate Jews took more active posts in the burgeoning women’s movement. Inspired by Betty Friedan and other prominent Jewish feminist leaders, Jewish female collegians awoke from a period of quiescence in the late 1960s and early 1970s and adopted more activist, politicized stances on issues such as feminism, abortion rights, and the Equal Rights Amendment.

By the early 1970s, Jewish women began to surpass their non-Jewish counterparts in terms of the percentage of females compared to males of the same religious faith. A study conducted in 1971 at the University of Maryland revealed that while females comprised fifty-nine percent of the population of Jewish students, they made up only forty-seven percent of the non-Jewish student population. The study also determined that Jewish women maintained a greater sense of ethnic and religious identity than did their Jewish brothers. For example, the percentage of female Jewish students belonging to Hillel exceeded that of males by more than six percentage points (18.9 to 12.7). In addition, 66.7 percent of Jewish women declared that their dates were “usually or always” Jewish, compared to only 54.9 percent of males making the same claim. Finally, whereas 37.5 percent of Jewish women asserted that they would not intermarry, only 26.8 percent of the male Jews were willing to make this statement. Thus, in addition to outnumbering Jewish males on the Maryland campus, Jewish females, according to the study, possessed more developed senses of cultural and ethnic consciousness and religious affiliation than did their male counterparts.

With the Jewish Greek system on the decline for both males and females, the rise in celebrations of ethnicity and ethnic consciousness in the late 1960s and 1970s created an environment favorable to the growth and spread of new Jewish-identified organizations. Groups founded in support of Israel and dedicated to taking political stances on Jewish issues sprang up on campuses and claimed Jewish female support. Beneficiaries of a campus environment more supportive of their presence than ever before, Jewish women continued to flock to college in increased numbers and to play more prominent roles within campus life.

Affirmative Action

In the 1970s, two Supreme Court cases highlighted the different positions of Jewish men and Jewish women regarding affirmative action in higher education. DeFunis v. Odegaard (1974) and Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) galvanized three male-led organizations—the American Jewish Committee (AJC), the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), and the American Jewish Congress (AJCongress)—around opposition to affirmative action. In order to defend their recent and hard-won gains in combatting employment and education discrimination and ending university quotas, the AJC, ADL, and AJCongress filed amici curiae briefs in support of Marco DeFunis and Allan Bakke, thus against affirmative action. Notably, the National Council for Jewish Women (NCJW) did not support DeFunis in 1974, instead signing, along with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and Commission on Social Action, onto the Children’s Defense Fund’s amicus brief in support of DeFunis, written by Marian Wright Edelman. Four years later, NCJW filed no amicus brief, neither in support of nor against Bakke.

Jewish women stood to gain from programs aimed at remedying disparities in employment and education for both racial minorities and for women, since they generally held “pink collar” jobs, which historian Nancy MacLean writes, “meant less money, more limited life chances, poor benefits if any, and less economic security” (MacLean, 7). As MacLean writes, women both within the three male-led organizations and outside it expressed their hesitation about opposing affirmative action, precisely because it could benefit Jewish women. As then-Congresswoman Bella Abzug said succinctly: “’I would like to remind my brothers that in attacking affirmative action programs in higher education as producing reverse discrimination against Jews…, they are talking about and speaking for Jewish men, not for Jewish women’” (quoted in MacLean, Freedom is Not Enough, p. 212). Jewish women not only expressed their dissatisfaction but also tried to alter the actions of their counterparts in male-led organizations. The AJC released a letter to presidential candidates Richard Nixon and George McGovern in 1972, calling on them to “reject categorically the use of quotas and proportional representation” in civil rights efforts (MacLean, p. 186). Afterwards, representatives from the AJC met with officials from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) to plead their case against “reverse discrimination.” In response, women within the AJC asked that women be considered in conversations between AJC and HEW, requesting that “we not refer only to Jewish men when we ask ‘What will be the impact [of HEW affirmative action policies] on Jews” (MacLean, p. 192). Privately, AJC director Bertram Gold acknowledged that affirmative action policies impacted Jewish women differently from Jewish men, but he made no changes to his organization’s strategy or position to account for it.

Jewish Female Collegians in the 1980s and 1990s

According to the Current Population Survey performed by the Department of Labor in 1990, by the late 1980s Jewish women had achieved a higher level of education than their non-Jewish white female counterparts. Whereas the study found that over half of the Jewish women in America held at least a bachelor’s degree, and over twenty-five percent of Jewish women held a graduate or professional degree, by 1990 only seventeen percent of white female non-Jews had received a bachelor’s degree and less than five percent had earned a graduate or professional degree. This high level of educational achievement signaled a shift within the Jewish community away from drawing a distinction between the educational paths of female and male children. At the same time, though, while both Jewish males and females possessed higher levels of education than their non-Jewish white counterparts, Jewish men still outranked Jewish women in numbers of years of education. The 1990 study showed that whereas 49.5 percent Jewish women over eighteen had spent four or more years in college, more than sixty percent of their Jewish brothers had achieved this feat. And although more Jewish women than men held high school degrees, the percentage of men who had earned college degrees topped the percentage of women by more than fifteen: sixty-six percent compared to fifty percent.

The 1990s saw a new wave in campus organizations at the intersection of Jews and gender. First, the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute at Brandeis University opened in 1997 (then called the Hadassah International Research Institute on Jewish Women). Today the Institute hosts a variety of events and programming, including residencies for scholars, a convocation series, and internships for undergraduate and graduate students for researching Jews and gender. In 1998, six women at University of California-Davis founded a new network of Jewish sororities, Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi (SAEPi), which raises funds for the American Jewish World Service and other nonprofits. As of 2022, SAEPi had fifteen active chapters across the United States.

In the last few decades of the twentieth century, Jewish women overcame many of the obstacles to their collegiate success posed by religious and cultural opposition, sexism, and antisemitism. By the late 1990s, the number of Jewish women receiving a collegiate education had reached a greater degree of parity with Jewish men. Approximately 125,000 Jewish women attended college, comprising eight-five percent of the Jewish female population between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four. This number and percentage mirrored the number and percentage of Jewish men earning a college degree during that same period.

The Twenty-First Century

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, women had actually become a slim majority of the total Jewish college student population, representing fifty-one percent of the 271,000 Jewish undergraduates aged eighteen to twenty-nine in the United States. Surveys conducted at this juncture identified some of the trends among Jewish college students of both sexes: Twenty-seven percent of all Jewish college students claimed affiliation with Hillel, which had become the largest Jewish campus organization in the world; incoming freshmen expressed a stronger commitment to raising a family than their parents had; and just over one-quarter of all Jewish collegians said they had experienced some form of antisemitism during the previous year, slightly more than the general Jewish population.

In 2020, the American Jewish Population Project of Brandeis University recorded that sixty-seven percent of Jewish women between twenty-five and thirty-four were college graduates, compared to fifty-eight percent of Jewish men. These numbers follow the trend generally between men and women in the United States. Many Hillel and Chabad chapters maintain women’s and LGBTQ groups. Students at Tufts University, Barnard College, and elsewhere host alternative programming to Hillel and Chabad chapters, with events relating to Jews and gender.

In the past decade, Jewish institutions have renewed their focus on college students, as reflected in the many guides to Jewish life on campus, which include measures of gender and sexuality in their calculations. While Hillel International began publishing a college guide in 1955, The Forward and other publications created their own guides for high school students to learn about how prospective campuses rank in regard to criteria such as presence of a Hillel Student Organization, kosher food access, and Israel activism. The Forward explained its criteria: thirty-four of one hundred points were given for “Jewish life,” twenty points for academics, twenty points for Israel activity, fifteen points for affordability, and eleven points for safety. Six of the eleven points for safety reflect the prevalence of anti-Semitism on campus, while the five remaining points “include other factors that impact how safe a student feels on campus, including the presence or absence of a campus LGBT center, the campus and city crime rates per capita, and the prevalence of crimes covered by the Violence Against Women Act, such as domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault and stalking.” This allocation of points under the banner of “safety” reflects the attention to sexual harassment and assault, particularly on college campuses and in the wake of #MeToo.

Between the late nineteenth century and the twenty first century, Jewish women negotiated their place in higher education institutions. While the attendance and success of Jewish women in college have waxed and waned in relationship to formal and informal admission policies, as well as restrictions and expansion of higher education opportunities, what remains consistent is the interest in pursuing education and organizing themselves to support each other, their schools, and their community.

Adkins, Laura E. “By The Numbers: The Forward’s College Guide Formula, Explained.” The Forward, August 8, 2018; https://forward.com/life/377875/by-the-numbers-the-forwards-college-guide-formula-explained/.

Baird, William Raimond. Baird’s Manual of American College Fraternities. 7th ed. (1912; also, 10th–17th editions).

Baum, Charlotte, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel. The Jewish Woman in America (1976).

Brown, Francis J., ed. “Discriminations in College Admissions: A Report of a Conference Held under the Auspices of the American Council on Education in Cooperation with the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, Chicago, Illinois, November 4–5, 1949.” In American Council on Education Studies 14 (April 1950).

Eagan, Eileen. Class, Culture, and the Classroom: The Student Peace Movement of the 1930s (1981).

Fass, Paula S. The Damned and the Beautiful: American Youth in the 1920s (1977).

Fishman, Sylvia Barack. A Breadth of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community (1993); Glazer, Nathan. Remembering the Answers: Essays on the American Student Revolt (1970).

Greenberg, Michael and Seymour Zenchelsky. “Private Bias and Public Responsibility: Anti-Semitism at Rutgers in the 1920s and 1930s.” History of Education Quarterly 33 (Fall 1993): 460–319.

Gurock, Jeffrey S. The Men and Women of Yeshiva: Higher Education, Orthodoxy, and American Judaism (1988).

Hartman, Moshe, and Harriet Hartman. Gender Equality and American Jews (1996).

Hillel International. “About the College Guide”; https://hillel.org/college-guide/about-the-college-guide, accessed 15 June 2022.

Hillel: The Foundation for Jewish Campus Life website (2001).

Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Campus Life: Undergraduate Cultures from the End of the Eighteenth Century to the Present (1987).

“Jewish College Students.” National Jewish Population Survey. United Jewish Communities: The Federations of North America (2000).

Koltun, Elizabeth, ed. The Jewish Woman: New Perspectives (1976); Lavender, Abraham D. “Jewish College Women: Future Leaders of the Jewish Community?” The Journal of Ethnic Studies 5 (1977): 81–90.

MacLean, Nancy. Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Marcus, Jacob R. The American Jewish Woman: A Documentary History (1981).

Markowitz, Ruth Jacknow. My Daughter, The Teacher: Jewish Teachers in the New York City Schools (1993).

McWilliams, Carey. A Mask for Privilege: Anti-Semitism in America (1948). National Panhellenic Congress. Minutes of Fifteenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Congresses (1917, 1923, 1926).

Newcomer, Mabel. A Century of Higher Education for American Women (1959); Oren, Dan A. Joining the Club: A History of Jews and Yale (1985).

Ritterband, Paul, and Harold S. Wechsler. Jewish Learning in American Universities: The First Century (1994).

Rosin, Nurite. Telephone interview by author, January 13, 1997.

Rosovsky, Nitza. The Jewish Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe: An Introduction to an Exhibition Presented by the Harvard Semitic Museum on the Occasion of Harvard’s Three-Hundred-Fiftieth Anniversary, September 1986 (1986).

Rothman, Stanley, and S. Robert Lichter. Roots of Radicalism: Jews, Christians, and the New Left (1982).

Sanua, Marianne. “Jewish College Fraternities and Sororities in American Jewish Life, 1895–1968: An Overview.” Unpublished paper with accompanying notes.

Sapinsky, Ruth. “The Jewish Girl at College.” In The American Jewish Woman: A Documentary History, edited by Jacob R. Marcus (1981).

Sax, Linda J. “America’s Jewish Freshmen: Current Characteristics and Recent Trends among Students Entering College.” Cooperative Institutional Research Program Survey (2002).

Scheckner, Jeff. Telephone interview by author, January 13, 1997.

Schneider, Susan Weidman. Jewish and Female: Choices and Changes in Our Lives Today (1985).

Schoem, David, ed. Inside Separate Worlds: Life Stories of Young Blacks, Jews, and Latinos (1991).

Schwartz, Howard. Jewish College Youth Speak Their Minds: A Summary of the Tarrytown Conference (1969).

Shosteck, Robert. “Five Thousand Women College Graduates Report: Findings of a National Survey of the Social and Economic Status of Women Graduates of Liberal Arts Colleges of 1946–1949.” B’nai B’rith Vocational Service Bureau (1953).

Solberg, Winton. “Early Years of the Jewish Presence at the University of Illinois.” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation (Summer 1992): 215–245.

Solomon, Barbara Miller. In the Company of Educated Women: A History of Women and Higher Education in America (1985).

Steinhardt Social Research Institute. American Jewish Population Estimates 202: Summary & Highlights. Brandeis University, 2021; https://ajpp.brandeis.edu/documents/2020/JewishPopulationDataBrief2020.pdf, 22

Synot, Marcia Graham. “Anti-Semitism and American Universities: Did Quotas Follow the Jews?” In Anti-Semitism in American History, edited by David Gerber (1986).

Toll, George S. “Colleges, Fraternities, and Assimilation.” Journal of Reform Judaism (1985): 93–103.

Wechsler, Harold S. The Qualified Student: A History of Selective College Admissions in America (1977).