Hasmonean Women

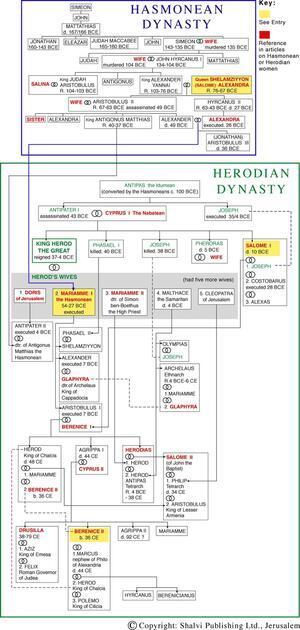

No woman of the Hasmonean family is mentioned in the two books devoted to the Hasmonean rebellion—Maccabees I and II, the authors of which showed no interest in the families of the Hasmonean brothers. Yet Hasmonean women seem to have played a decisive role in the history of the dynasty, particularly as regards the succession process. They were targets of torture and execution, participants in political negotiations, and members of resistance movements.

Article

No woman of the Hasmonean family is mentioned in the two books devoted to the Hasmonean rebellion—Maccabees I and II, the authors of which showed no interest in the families of the Hasmonean brothers. Yet Hasmonean women seem to have played a decisive role in the history of the dynasty, particularly as regards the succession process. This cannot be contested, in light of the fact that this dynasty produced the only legitimate queen in Jewish history (see Shelamziyyon Alexandra). Yet the queen is hardly the only Hasmonean woman who made an impression on history. All we know of these women comes from the works of Josephus, but Josephus himself obviously relied on earlier sources for his description of them. Whatever this earlier source (or sources) was, it was probably written in the same tradition as the books of Maccabees: it documented the women’s actions, but did not see fit to document their names. Thus they can only be described as relatives of their menfolk.

Wife of Simon the Hasmonean (d. 135 B.C.E.)

We hear nothing about her before the last days of her life, but an allusion to her may be found in the slanderous account of the circumstance of the birth of her son John Hyrcanus. It was suggested by his political opponents that he should not hold the office of High Priest because his mother had been held prisoner by the Seleucids just prior to his birth and might have been raped, thus raising some doubt about his true father. (Ant. 13:292). Chronology allows for such a scenario.

This woman apparently bore her husband three sons and a daughter. We first hear of her when she and her husband and two of their sons were taken hostage and then murdered by Simon’s son-in-law. After the execution of her husband, when her remaining son, John Hyrcanus, set out to attack his father’s murderer, his mother was brought out on to the turrets of the castle in which the perpetrator was hiding and tortured before her son’s eyes, so as to induce him to desist from his military campaign. We are told that she encouraged him to ignore these actions and continue his pursuits. In the end, however, Hyrcanus did not conquer the castle and his mother was executed (Ant. 13:230–235). Since the story is very dramatic but has no specific historical consequences we may wonder whether it was not inserted into the narrative simply for its dramatic effect.

Wife of John Hyrcanus (d. 104 B.C.E.)

We hear of this woman only at the time of her husband’s death. We are informed that she was nominated by her husband to succeed him to the throne. However, this was not to be. Her son Judah Aristobulus seized the throne and starved his mother to death (Ant. 13:302). Yet she remains the precedent that allowed Shelamziyyon, her daughter-in-law, to indeed become queen a generation later.

Wife of Judah Aristobulus I

We apparently know the name of this woman, who was called Salina (or Salome) Alexandra. After the death of her husband she released his brothers from prison and nominated Alexander Yannai king (Ant. 13:320). We know nothing more about her, although many modern scholars assume she then married Yannai, and that she is queen Shelamziyyon, though this cannot be proven.

Wife of Aristobulus II

This woman, it seems, was very close to her husband (Ant. 13:424), as one may infer from two episodes in which she is circumstantially mentioned. In the first, she is taken hostage by Queen Shelamziyyon, who, on her deathbed, tried to deter Aristobulus II (the queen’s younger son) from seizing the throne on her death (13:426). Since the story has no continuation we do not know how successful this action was. Several years later, when her husband led the Jewish resistance to Roman occupation, we find the Roman leader, Gabinius, negotiating with her to allow her husband’s surrender at Machaerus (Ant. 14:97). What she did after her husband died in 49 B.C.E. at Rome is not known.

Sister of Mattathias Antigonus (d. 30 B.C.E.)

The daughter of Aristobulus II she apparently participated in Jewish resistance against Rome like her father and two brothers. This we infer from a single reference to her by Josephus, who mentions that, even after her brother was defeated and executed by Rome, and even after Herod controlled all the country, she continued to hold the fortress of Hyrcania in the Judaean Desert and resist Herod for up to seven years (Josephus, BJ 1:364).

Alexandra (d. 26 B.C.E.)

We know more about this woman, as well as her name, because she lived much of her life in the Herodian court. Nicolaus of Damascus, Herod’s court historian, who usually documented Herodian women’s names, documented her actions. She was the daughter of Hyrcanus II, the Hasmonean who chose to ally himself with Rome. Yet in 55 B.C.E. she married her cousin, Alexander son of Aristobulus, who was a mortal enemy of Rome all his life. They had two children, Aristobulus III and Mariamme, Herod’s wife. In 49 B.C.E. she was widowed when her husband was executed by the Romans. This brought her directly into the Herodian court. In 37 B.C.E. her daughter married Herod.

In 36 B.C.E. Alexandra’s 17-year-old son, just nominated High Priest, drowned in mysterious circumstance in the winter palace at Jericho (Ant. 15:50-6). Nicolaus describes Alexandra’s attempts to accuse Herod of murder in these circumstances as a woman’s political network. She wrote to Cleopatra in Egypt about her suspicions and Cleopatra persuaded her lover Mark Anthony to summon Herod to explain the event (Ant. 15:62–64). Herod, however, succeeded in persuading Anthony of his innocence. Yet Nicolaus continues to describe Alexandra as an incessant intriguant. She attempted to escape to Egypt, fleeing Herod’s surveillance (Ant. 15:42–47). She persuaded her father to ally himself with the Nabatean king against Herod (Ant. 15:166–168). She persuaded her daughter to escape to the Roman legions when Herod was away and out of favor (Ant. 15:71–73). Thus she was, at least according to Nicolaus, responsible for Mariamme’s fall from favor with Herod. In order to further enhance the description of her vile nature, Nicolaus described her betrayal of her daughter when the latter was led to her execution, cursing her and reviling her on her way (Ant. 15:232–234).

However, Alexandra too, like all other Hasmoneans (male or female) in Herod’s court, found her death at the hands of Herod. After Mariamme’s execution, she once again attempted to gain control of the army and lead an insurrection against Herod. The plot was discovered and Alexandra executed, just one year after her daughter (Ant. 15:247–251)

Ilan, Tal. “Queen Salamzion Alexandra and Judas Aristobulus I's Widow:

Did Jannaeus Alexander Contract a Levirate Marriage?” Journal

for the Study of Judaism 26 (1993): 181–190.

Discusses the chronological and onomastic difficulties arising from the identification

of the queen with the widow of Judas Aristobulus.

Ilan, Tal. Integrating

Jewish Women into Second Temple History.

Tübingen: 1999. “Things Unbecoming a Woman” (Ant.

13:431) Josephus and Nicolaus on Women, 85–125.

In this chapter Ilan discusses the differences in the portrayal of Hasmonean

and Herodian women in Josephus and tries to account for it by reference to

the sources on which they rely.

Schalit, Abraham. König

Herodes: Der Mann und sein Werk, 563–644. Berlin: 1969.

In this chapter, Schalit discusses Herod’s court and family affairs. He devotes

a large section to Alexandra’s exploits.

Sievers, J. “The Role of Women in the Hasmonean Dynasty.” In Josephus,

Bible and History, edited by Louis H. Feldman and Gohei Hata, 132–146.

Detroit: 1988.

This article attempts to generalize about the unique role of Hasmonean women

in Second Temple history.