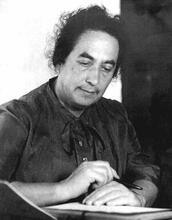

Clara Haskil

Photograph of gifted classical musician Clara Haskil. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Despite constant pain from scoliosis and a tumor on her optic nerve, pianist Clara Haskil became renowned for the purity of her interpretations of classical composers. An early prodigy, Haskil entered the Paris Conservatoire at age ten in 1905 and graduated in 1910, although her debut concert tour across Europe was interrupted by her scoliosis. Despite her physical challenges, she performed with many of the great musicians and conductors of her time and was awarded the French Légion d’Honneur. Although primarily known for her piano playing, she also studied violin and occasionally traded instruments with great violinists for duets. She died from injuries sustained falling at a train station in Brussels. In 1965, the Clara Haskil International Piano Competition was created in her honor.

Early Life and Family

Clarity, delicacy, and virtuosity, the hallmarks of Haskil’s playing, made her ideally suited for performances of Mozart which, in musicologist Peter Gradenwitz’s words, “transported the listener into a subliminal world of pure music.” Her repertoire, largely comprising the Romantic canon, belied her physical frailty; she suffered from pneumonia as a small child and was forced to spend four adolescent years in plaster due to scoliosis, the curvature of the spine. The removal in 1941 of a tumor on the optic nerve left her with severe headaches that augmented her unremitting backache.

The second of three daughters of a Sephardi Jewish family living in Bucharest, Clara Haskil was born on January 7, 1895. Her sisters became musicians, Lili, the older, was a pianist, and Jeanne, the younger, a violinist who claimed, “We have talent, but Clara has genius.” Isaac, their father, was a member of a well-regarded family who had immigrated to Romania from Bessarabia. It seems probable that Isaac’s marriage, at the age of thirty-two, to Berthe Moscona met with disapproval, since Berthe’s background was particularly straitened. She was the third of six children born to David and Rebecca Moscona; whilst David was well educated, his child-bride Rebecca Aladjem was virtually illiterate, although she later learned to read and write and possessed an extraordinarily retentive memory. David abandoned his family, fleeing to Vienna and leaving Rebecca to bring up their young children on the small income subsequently provided by the Jewish community. All the children were gifted; the second, Clara, was an exceptional musician, who tragically died at twenty. Berthe, Rebecca’s third child, named her second daughter after this sibling. Avram, the fourth of Rebecca’s children, was a talented scientist who won a scholarship to study medicine in Vienna, and it was he who was to devote himself to the musical career of his niece, Clara.

At the age of twenty-four, Berthe married Isaac Haskil. The home, in which music played a central role, was happy, situated in an apartment above the family household-goods shop. The Haskils were not religious, although they retained an awareness of their Jewish roots, confirmed by the short bedtime prayer Berthe would recite with the children. Tragically, Isaac’s death from pneumonia in 1899 left Berthe alone to bring up her three daughters when the youngest, Jeanne, was barely a year old

Music Education and Early Career

When Clara was not yet five, a colleague of her uncle Avram was so struck by her piano playing that he took her to Georges Stefanesco, professor of singing at the Bucharest Conservatory, and in 1901 Clara, who had hitherto been taught by her mother, was admitted to the Conservatory, where she studied for a year. In April 1902 Avram took her to Vienna, where he had settled; Clara quickly mastered the language, despite retaining an idiosyncratic pronunciation and turn of phrase throughout her life. The ensuing three years were spent under the tutelage of the renowned teacher Richard Robert, who provided the basis of her formidable technique. Childless, he and his wife virtually adopted Clara, who struck up a friendship with George Szell, another of Robert’s young pupils.

Soon after her arrival in Vienna, Clara was overwhelmed on hearing Joachim playing Brahms, and so took up the violin, which she ceased studying after leaving Vienna and to which she devoted no time for practice. Nevertheless, Peter Rybar, the Swiss violinist, notes her idly picking up a violin during a break in a concert rehearsal many years later, in 1944, and describes her exquisite phrasing and impeccable intonation. Throughout her career, Haskil performed with legendary string players such as Eugène Ysaÿe, Georges Enesco, Pablo Casals, Yehudi Menuhin, Henryk Szeryng, and Isaac Stern, as well as her sister Jeanne.

Richard Robert recommended Clara to Gabriel Fauré, then principal of the Paris Conservatoire, who was particularly impressed with her, and in 1905 she entered the Conservatoire, joining Alfred Cortot’s class in 1907 and graduating in 1910 at the age of fifteen, with the Premier Prix. She embarked on a series of concert tours throughout Europe, but her career was interrupted by developing scoliosis, which had become apparent at the age of thirteen, and the recommendation that she spent four years in a nursing home encased in a cast. In 1921 she again began to perform in public, with Paris as her base, where first her uncle and then her mother and sisters took care of her. The outbreak of World War II and the subsequent occupation of France forced her to escape to Marseilles in the unoccupied zone. It was here, in 1941, that a Jewish surgeon traveled from Paris to perform the hazardous operation to remove the tumor in Haskil’s eye.

Later Career and Legacy

Despite her physical frailty and the exacting musical demands she made on herself, she resumed her international career, performing throughout the world and appearing at the most prestigious music festivals under the baton of conductors such as Eugene Istomin, Carl Munch, Carlo Maria Giulini, Sir John Barbirolli—having played with the Hallé Orchestra in England in 1926 under Sir Hamilton Harty—and Sir Thomas Beecham. She moved to Vevey in 1951, and the French subsequently appointed her a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur.

On Tuesday, December 6, 1960, a month before her sixty-sixth birthday, Haskil arrived in Brussels, accompanied by Lili, to begin a concert tour with Belgian violinist Arthur Grumiaux, after a triumphant performance they had given in Paris. At the railway station, she slipped, fell down the stairs, and was rushed to hospital unconscious. Jeanne quickly came to join her sisters before Clara died in the early hours of the following morning. In the words of the conductor Ferenc Fricsay, “With the death of Clara Haskil we have become the poorer, but our existence has been enriched by her life.”

Feuchtwanger, Peter. “The Perfect Clara Haskil.” Clavier, 39/7 (September 2000): 25 f.

Gavoty, Bernard, and Roger Hauert. “Clara Haskil.” In Les Grands Interprètes. Geneva: 1962.

Morrison, Bryce. “Clara Haskil.” New Grove Dictionary II, Vol. 11. London and New York: 2001.

Spycket, Gérôme. Clara Haskil. Lausanne: 1975.