English-Language American Jewish Women’s Magazines, 1895-1945

From the end of the nineteenth century, American Jewish women were involved at all levels of the buoyant magazine boom spreading through the United States. Drawing from various inspirations and models, Jewish women began publishing their own magazines, representing their ideologies and defending their interests. Whether associated with Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, Zionist, or literary groups, these publications reflected women’s political, social, cultural and religious concerns. Through editorials, portraits, interviews, literary works, and book reviews, these magazines reflect the diversity of American Jewish women in the first half of the twentieth century, as well as their editorial, literary, and journalistic talents, too often dismissed.

Overview of Jewish Women’s Magazines

In April 1895, the first issue of the American Jewess was published in Chicago, Illinois. For four years, its editor, the vibrant and brilliant Rosa Sonneschein, born in Hungary, used the paper as “a medium of exchange” through which its readers could “keep in touch with [their] sisters this broad land over.” She claimed that it was the first English-language magazine published by and for Jewish women in the United States. Although short-lived, this pioneering publication paved the way for a variety of Jewish women’s magazines, edited by women and intended for female audiences, throughout the early twentieth century.

Beginning in the 1890s, a variety of magazines emerged from the editorial hands of Jewish women across the country. These publications reflected the growth of the newspaper industry at the end of the nineteenth century. As more women joined the staffs of newspapers and magazines nationwide, and as women’s magazines emerged and modernized (like the Ladies’ Home Journal under Edward Bok’s editorship from 1889 to 1919), many Jewish women saw an opportunity to carve out a specific space to express their voices in print.

Some publications, like the American Jewess, lasted only a few years, while others, such as the Women’s League for Conservative Judaism's Outlook, are still being published today. Most were published monthly but some appeared bimonthly or quarterly. They ranged from only a few pages to as much as 70 pages per issue. While all these publications claimed to cater to the needs of American Jewish women, each represented the interests of particular political, religious, and cultural movements aligned with Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, or Zionist groups. Despite their ideological differences, all endeavored to create a platform for like-minded American Jewish women, to educate and inform them about contemporary issues, and to promote their own vision of the “ideal” American Jewish woman.

Most Jewish women’s magazines were published by national Jewish women’s clubs, serving as a link between the individual members in the local sections and the national organization. Jewish women’s clubs, like their Christian counterparts, burgeoned in the 1890s, providing organizational spaces for Jewish women to join together around issues such as philanthropy, religion, politics, or social work.

Estelle Sternberger emerged from bourgeois beginnings to become a powerful voice for left-wing social causes, first as a writer and later as a successful radio commentator.

Institution: The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, www.americanjewisharchives.org and Camera Associates

While the American Jewess (1895-1899) never officially became the organ of the National Council of Jewish Women (NJCW), it was closely associated with the organization and most of its readers were Council members. In the 1920s, the NCJW launched an ambitious official organ of its own: The Jewish Woman (1921-1931), edited by Cincinnati-born Estelle M. Sternberger, who later became a renowned radio broadcaster. The NCJW went on to publish Council Woman from 1940 into the 1950s.

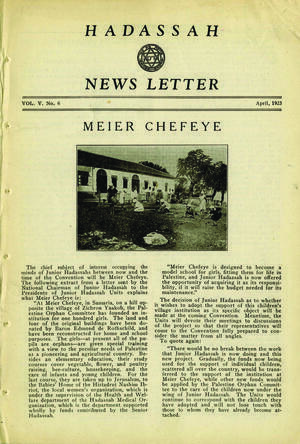

Other groups followed suit. The Women’s League for Conservative Judaism debuted its magazine, the Outlook, in 1930. The National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods (NFTS), the Reform women’s organization, started publishing its organ, Topics & Trends, in 1934. Under the editorship of Jane Evans, executive director of the NFTS, the four-page publication set out to establish “a desirable connecting link between the National and the individual members.” As Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, gained a following, it too produced a range of publications, edited over the years by various skilled women who sat on its national board. Through its Bulletin (1914-1918) and News Letter (1920-1961), the Zionist organization broadcast its activities and published news of relevance to its local chapters.

This rich array of Jewish women’s national magazines showcases both the diversity and editorial expertise of Jewish women in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century, as they eagerly embraced the expanding Jewish print culture of the era.

A Medium of Exchange

Jewish women’s publications aimed to create a reading hub and point of contact for the English-speaking Jewish women of the United States. While local sections of clubs often published newsletters or bulletins, typically listing programs for the upcoming week, the national magazines went beyond announcements and updates. They operated as a broader medium of exchange, connecting the Jewish women scattered throughout the United States. These magazines included news from local sections, letters to the national board, and responses to questions about the club’s national activities. They also featured articles that addressed broader concerns, ranging from religious education to marriage to work for women and more.

The Ordens Echo, first published in German in 1897, exemplifies the evolving role assumed by Jewish women’s magazines. As the official publication of the United Order of True Sisters (UOTS), created as a female counterpart to the male B'nai B'rith organization, the Ordens Echo originally operated as a weekly newsletter. The publication grew and gradually began incorporating articles in English to accommodate a younger, more Americanized readership. As UOTS expanded and new lodges were created throughout the United States, the Echo served the role of a “printed messenger,” containing summaries of Lodge meetings, presidential messages, reports of festivals, and correspondence from the lodges. It provided a space for like-minded sisters to share ideas, concerns, and aspirations, under the guidance of “Mother” Bianca B. Robitscher, founder and editor until her death in 1924.

In this way, these magazines allowed Jewish women across the country to keep in touch with one another, to be informed of each other’s activities, and to conceive of themselves as part of the wider Jewish women’s community.

Advocacy and Education

Beyond stitching together the activities of local clubs, Jewish women’s magazines set national agendas and priorities as they educated women on a range of religious, social, or political issues. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, articles on suffrage and immigration filled the pages of these publications, detailing the debates shaking the political sphere and explaining legislation being proposed and passed. By the 1930s, the rise of Nazi Germany and antisemitism in the United States became central themes of the magazines. Each editorial board had the power to choose which news to broadcast and how to shape the discourses around controversial issues. What was discussed was as relevant as how it was broached, and who was given a say.

Cover of the Hadassah News Letter, April 1925, in which members discussed supporting Meier Chefeye, which later became one of the Youth Aliyah villages that saved young Jews during World War II. Now known as Meir Shfeyah, today it is a home for at-risk youth and is still supported by Hadassah. Courtesy of Hadassah, The Women's Zionist Organization of America, Inc.

As magazines circulated, they not only informed and educated readers but actively recruited them for the causes and organizations they represented. Hadassah relied heavily on its publications to inspire both current and prospective members about the mission of women in Zionism. In April 1925, with the expansion of its work in Palestine, Hadassah’s leaders gathered articles from the News Letter in a twelve-page pamphlet that detailed the needs and activities of the Hadassah Medical Organization. Designed for use in fundraising campaigns, excerpts from the News Letter became publicity to sway Jewish women to support Hadassah’s efforts.

Other magazines also worked to transform readers into supporters of their particular callings. The NCJW was often referred to as the “Great Interpreter” of Judaism, and its magazine, The Jewish Woman, took this intermediary role to heart. Editor Estelle M. Sternberger continuously featured articles offering pointed views on societal issues. In the January 1926 issue, an article written by Philadelphian Rose S. De Young was published. Entitled “My Experience as a State Legislator,” it showcased the obstacles the author had to overcome in her political career, while reminding every reader that, whether they liked it or not, women had a duty to participate in the political life of the country. This article reinforced the Council’s civic policy of encouraging women to educate themselves on political matters and to exercise their right to vote, which they had won a few years prior with the Nineteenth Amendment.

Women Writers and Women Editors

The sheer diversity of publications outlined here demonstrates that magazines and bulletins came to occupy a distinct and expanding role among American Jewish women. Jewish women also had access to several Yiddish, Ladino, and German publications—mostly published by men—beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, and reading options increased exponentially over the decades that followed.

By the turn of the twentieth century, a new phenomenon began to appear—the women’s pages that gradually became a regular feature of nearly every Jewish newspaper or magazine, regardless of language. These sections contributed content considered to be tailored to women, from advice columns to fashion tips to articles on child-rearing. Although these columns offer tremendous insight into Jewish women’s lives and interests, they mostly appeared in newspapers edited and controlled by men. Women writers of these columns generally worked within constraints not encountered by those who contributed to magazines edited by women.

Jewish women were active in all spheres of modern life, including the publishing industry. Although some Jewish women—such as Hattie S. Friedenthal who edited the Denver Jewish News between 1917 and 1922—managed to break free from the woman’s pages, American Jewish women’s magazines offered a privileged space for Jewish women writers, whether they were already attuned to the art of the quill or new to the field. In this arena, they participated as temporary writers, permanent contributors, editors, and members of editorial boards. Many magazines prioritized publishing articles written by women, as was the case with Council’s Jewish Woman and the UOTS Orden’s Echo. Moreover, women editors often curated the material they published, making decisions about which issues to foreground and highlight.

An ardent Zionist and advocate for an expanded role for women in the synagogue and religious community, Rosa Sonneschein founded and edited The American Jewess, which gave her a forum for those views.

Institution: The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, www.americanjewisharchives.org and the State Historical Society, MO

The American Jewess, the first of its kind, featured many contributions from Jewish men, perhaps as it aimed to establish the venture’s respectability. Yet even its pages included numerous articles by up-and-coming women writers. Moreover, editor Rosa Sonneschein regularly encouraged women to try their hand at writing by inviting submissions. In doing so, she envisioned her magazine as a training ground for women who might be casual contributors or might aspire to careers in journalism or literature. Although Sonneschein cautioned them about the challenges of the field, she underscored the legitimacy of their aspirations.

Other magazines also urged women to contribute to their issues, inviting readers to send short stories, essays, club reports of local sections, or topical articles. These invitations were accompanied by contributor guidelines and writing tips, to make sure that the style of the articles matched that of the publication. Many were willing to engage with their readers and incentivize them to become contributors, particularly through essay contests. The Immigrant, the monthly bulletin issued by the Department of Immigrant Aid of the NCJW, held an annual essay contest. Winners received both financial compensation and the opportunity to have their essays published in the bulletin.

Some magazines sought to make a mark on the literary world. Such was the case for the short-lived magazine Eve: Dedicated to the Modern American Jewess (1936-1937), whose editor was C. [Cordelia] Belle Makarius, a regular contributor to newspapers and radio broadcaster in the early 1930s. When launching Eve, Makarius and publisher Paul Ward Brody invited contributions pertaining to any topic of interest to Jewish women in America, as well as “light sophisticated fiction” and “articles on controversial subjects.” Between 1936 and 1937, women responded with pieces spanning short fiction, poetry, career advice, and portraits of “Eve’s Women of the Month.” While the magazine itself did not survive long, it received considerable praise in the mainstream Jewish press for its ambition and bold enterprise. The Californian B’nai B’rith Messenger welcomed the arrival of what it called “the Jewish Vanity Fair,” while the Detroit Jewish Chronicle envisioned the magazine as a “boon to Jewish journalism in this country.”

These magazines also provided Jewish women with valuable experience in editing and decision-making. Whether they were responsible for small newsletters or more substantial 50-page issues, women editors honed critical skills in managing their publications. Carrie Dreyfuss Davidson, who edited the Women’s League’s Outlook for 23 years until her death in 1953, dedicated much of her time to the monthly magazine, writing editorials and columns. The Outlook became a creative outlet for her, as well as for women who later became writers and contributors to a range of other Jewish publications. These included Mignon L. Rubenovitz, who wrote articles for Boston’s Jewish Advocate, and Althea O. Silverman who co-edited The Jewish Home Beautiful in 1941 alongside Betty Greenberg.

Despite the demanding and time-consuming nature of editing, the role was deeply rewarding. Women who edited these magazines felt that they were furthering the causes of the organizations they represented and regarded their work as a calling. Writer and future Hadassah President Tamar de Sola Pool, who edited its News Letter in the 1930s, stated that she loved this journalistic work above all else. The content that filled the pages of Jewish women’s magazines often depended on the vision of both the editor and the national group that sponsored the publication. Many women editors shared the outlook of their sponsors, but they also sometimes allowed for a degree of dissent. For example, the Jewish Woman proved willing to publish contradictory views on the same topic rather than imposing a strict ideological editorial line. Independent editors like Rosa Sonneschein and C. Belle Makarius, who were not bound to specific organizations, seemed to enjoy greater freedom in the topics and ideologies they could explore. But without the financial and organizational backing of established groups, they often had less institutional support in contending with advertisers and publishers.

Legacy and Post-World War II Magazines

The two independent magazines, the American Jewess (1895-1899) and Eve (1936-1937), had short runs, but other magazines enjoyed long and successful lifespans. Some publications evolved from newsletters into larger modern magazines. For example, the original Outlook ran until 2007, before being revived as the New Outlook for Women’s League in 2016. The Hadassah News Letter transitioned into Hadassah Magazine in 1961 and, as one of the largest-circulation Jewish publications in America, still covers politics, news, and culture related to Israel and Jewish life with a special emphasis on women. The Echo continued to be published into the 1970s, changing publication formats along the way to fit the modernizing magazine industry. Other newsletters and magazines took on new forms, for example the Topics & Trends newsletter of the NFTS became a four-page section entitled “Sisterhood Topics” in American Judaism, the magazine of Reform Judaism.

After World War II, a number of independent Jewish women’s magazines emerged to give voice to the diversity of Jewish women’s experiences in America. In the 1970s, the Jewish feminist movement gave rise to Lilith, founded in 1976 by a group of women led by Susan Weidman Schneider, that still exists today. As a Jewish feminist magazine, its pages continue to feature bold reporting, memoirs, original fiction, poetry, and articles on a variety of topics of interest to Jewish women. In 1990, another group of Jewish feminists launched Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and our Friends. Envisioned as an artistic and cultural publication, the magazine consciously included the experiences of lesbian, leftist, working-class, and feminist Jews to showcase the diversity of Jewish experiences and provide an inclusive space for Jewish women who had been marginalized. The journal survived until 2011.

The continued vitality of Jewish women’s magazines today is a testament to the foundation laid by their predecessors. Far from being a mere footnote in the history of American Jewry, these publications played a central role in shaping the lives of Jewish women through the first half of the twentieth century. Their editorial strategies, networks of women writers, and influence on public discourse demonstrate the role that print played in shaping the lives of American Jewish women in the first half of the century.

Primary Sources

Selected Magazines and Bulletins

American Jewess (1895-1899). Founded and edited by Rosa F. Sonneschein (April 1895-January 1899). The entire original text and images of the magazine can be accessed and searched online at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/amjewess/.

Bulletin (1914-1918) and News Letter (1920-1961) published by Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America. RG17/Printed Materials, Hadassah Archives on Long-term Deposit at the American Jewish History Society, I-578.

Council Woman (1940-1977). Published by the National Council of Jewish Women. https://lccn.loc.gov/43034005, E184.J5 C74, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Eve: Dedicated to the Modern American Jewess (1936-1937). Founded and edited by C. Belle Makarius. New York Public Library, Call number *PBD (Eve). Vol. 1-2 (April 1936-April 1937). Vol. 3, no. 1 (May 1937).

Immigrant (1922-1930), bulletin of the Department of Immigrant Aid of the NCJW. Edited by Etta Lasker Rosensohn and Cecelia Razovsky.

Jewish Woman (1921-1931), published by the National Council of Jewish Women. Founded and edited by Estelle M. Sternberger. Vol. 1-11 (incomplete) available at HathiTrust, access granted by the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Ordens Echo (1897-1917), Echo (1917-1975). Published by the United Order of True Sisters. Founded and edited by Bianca B. Robitscher (1897-1924). MS-638, The United Order of True Sisters records. American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Outlook (1931-2007). Published by the Women’s League for Conservative Judaism. Founded and edited by Carrie Dreyfuss Davidson (1931-1951). ARC-2022-07, Women’s League for Conservative Judaism Records. Jewish Theological Seminary, New York City.

Topics & Trends (1934-1951) published by the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods. Founded and edited by Jane Evans. MS-73, Women of Reform Judaism records. American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Other primary sources

Alexandria, “New York Notes,” American Jewess, Vol. 1, n°4.

De Young, Rose S. “My Experience as a State Legislator.” Jewish Woman, Vol. 6, n°1.

Evans, Jane. Proceedings of the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods, 1933-1935: 19. Women of Reform Judaism Records, MS-73, Box 1, Folder 3. American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio.

“Eve—A Magazine for Women,” Detroit Jewish Chronicle, May 15, 1936.

“Journalese.” B’nai B’rith Messenger, combined with the California Jewish Review, March 27, 1936.

Robitscher, Bianca B. “Independent Order of True Sisters.” Hebrew Standard, April 5, 1907.

Secondary Sources

Balin, Carole B., Dana Herman, Jonathan D. Sarna, and Gary P. Zola, eds. Sisterhood: A Centennial History of Women of Reform Judaism. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 2013.

Batker, Carol J. “’Why Should You Ask for Ease?’: Jewish Women’s Journalism in the English-Language Press.” In Reforming Fictions: Native, African, and Jewish American Women’s Literature and Journalism in the Progressive Era. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Berrol, Selma. “Class or Ethnicity: The Americanized German Jewish Woman and Her Middle Class Sisters in 1895.” Jewish Social Studies 47 (1985): 21–32.

Brinn, Ayelet. A Revolution in Type: Gender and the Making of the American Yiddish Press. New York: New York University Press, 2023.

Fahs, Alice. Out on Assignment: Newspaper Women and the Making of a Modern Public Space. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Kuzmack, Linda Gordon. Woman’s Cause: The Jewish Woman’s Movement in England and the United States, 1881–1933. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1990.

Rogow, Faith. Gone to Another Meeting: The National Council of Jewish Women, 1893–1993. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Ruggles Gere, Anne. Intimate Practices and Cultural Work in U.S. Women’s Clubs, 1880-1920. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Schwartz, Shuly Rubin. The Rabbi’s Wife: The Rebbetzin in American Jewish Life. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Shapiro, Shelby. Words to the Wives: The Yiddish Press, Immigrant Women, and Jewish-American Identity. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2024.

Wilhem, Cornelia. The Independent Orders of B'nai B'rith and True Sisters: Pioneers of a New Jewish Identity, 1843–1914. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2011.