Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends

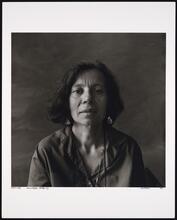

Pictured here is the editorial board of Bridges, a Jewish feminist publication whose issues reflect the multiplicity of Jewish experiences and identities within a context that values different voices, histories and languages.

Photograph by tova stabin.

Institution: Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and our Friends.

Bridges: A Jewish Feminist Journal connected Jewish feminist writers, activists, and artists with each other, and with various public forums, for more than two decades. As a project made by, for, and about Jewish feminists, it became a space of creative collaboration, and a place to showcase late twentieth-century Jewish feminist cultural production. With an editorial board that brought the politics of lesbian feminist identity work to the social and cultural development of diasporic belonging, Bridges became a remarkable space for the exploration and support of Jewish women’s impressive diversity. As the journal’s mission statement declared, from the feminist, lesbian, and gay movements, its commitments remained in “integrating analysis of class and race into Jewish-feminist thought and to being a specifically Jewish participant in the multi-ethnic feminist movement.”

Overview

“Bridges are connectors, spans between deeply rooted foundations, bridges allow communications and transactions. And, as the October 17, 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake showed us, bridges can be among our most vulnerable structures” (Atkin et. al, 1990, 5). As the editors of Bridges: A Jewish Feminist Journal wrote in the inaugural issue, a vulnerable structure can be a site of both danger and possibility. The publication featured Jewish women writers, artists, scholars, editors, and translators acknowledging violence, naming trauma, marking loss, grieving death, and excavating the past to glean its wisdom; these contributors formed the core of the journal, their shared vulnerability providing the project both its risk and its strength. Such vulnerability also facilitated contributors’ bravery in exploring a repeated theme of hope against despair, a cultural response to an era of political and economic restructuring that overturned gains won by the feminist and antiracist left. In a time known for backlash and fracture, Bridges offered space for critical analysis, political protest, connection, and creative communication, in the service of transformation towards justice and just peace.

The journal emerged in the overlap of late twentieth-century feminism and the Jewish left; together, the two movements, bridged by its pages, form the potent space of this remarkable archive. Its issues offer countless representations of Jewish feminist identity, culture, history, and politics. For just over twenty years, Bridges drew the margin to the center, at turns foregrounding lesbian, leftist, working-class, diasporic, non-white, and non-traditional Jewish women’s worlds, bound together in dialogue, in citation, and in critical engagement. Such intertextual architecture constructed bridges made of fiction, memoir, interviews, letters, news reports, family histories, documentary photography, poetry, criticism, reviews, art, obituaries, polemic—even, in the first issue, several works of music, written out as notation (Wetzler, Livingston, and Falbel, 1990); later, a Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic recipe for fritada made with matzo offered access to a classic dish that might otherwise have been lost in time (Simons 1997). Together, these voices created the dissonance and the resonance for which Bridges was known and loved.

Clare Kinberg: Animating Force

Bridges carried the language and the labor of hundreds of Jewish women and their closest interlocutors. But as with so many collective projects, its trajectory was substantially shaped by one creative and connective individual who was immersed in the work for decades. In 1976, Clare Kinberg was just 21 years old: a bright and budding radical lesbian feminist. As a clothing factory worker and a member of the Coalition of Labor Union Women, she strongly identified with the labor movement. Developing her lesbian feminist and literary practices simultaneously through the late 1970s, Kinberg joined the editorial collective of the journal Moonstorm, engaging in the creation of a lesbian feminist counterpublic through the underground press. In one example of her exploration of Jewish feminist working-class legacies, Kinberg penned an essay on Emma Goldman for Moonstorm. She mobilized feminist methods to explore the roots and routes of her identity, taking part in a multiracial, cross-class formation for lesbians organizing with other lesbians. But when the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon occurred, Kinberg’s understanding of herself, her identity, and her role in political struggle shifted—as it did for so many other Jewish feminists. Receiving the news of Israeli state violence with horror, Kinberg became attuned to the need for justice, peace, and liberation for Palestinian people. She understood this need through the lens of Jewish identity, and she sought to address Israeli state violence and a range of interrelated justice projects through the method of progressive Jewish multi-issue organizing.

Kinberg searched for Jewish people with whom to reckon and to organize. She soon came upon the local St. Louis chapter of New Jewish Agenda, a national organization that aimed to represent “a Jewish voice among progressives, and a progressive voice among Jews”—and was also on its way to becoming a feminist organization, with a robust lesbian and gay presence. Kinberg became one of the youngest members of the group. When local chapters across the country were called to send spokespeople to the national organizing body, she accepted a $200 gift from a friend to make the trip. Joining the leadership of New Jewish Agenda was the start of a new path for Kinberg, a movement space where she began to feel at home at a time when she felt increasingly estranged from identity-based, exclusive lesbian organizing. While other Jewish women in Moonstorm chose to continue organizing among lesbians, Kinberg took her lesbian self and her organizing to bring a distinct lesbian feminist presence to the emerging progressive Jewish movement. She went to her first National Council meeting for New Jewish Agenda in 1983 and was hired as the planner for the National Conference in 1985.

At that conference, Kinberg, along with Ruth Atkin, began the work to form a Feminist Task Force, to which she recruited the Jewish feminist writer-activists Adrienne Rich and Elly Bulkin. They were soon joined by Rita Falbel, Ruth Kraut, and Laurie White, and for several years the group of seven published an internal newsletter for New Jewish Agenda called Gesher (“Bridge” in Hebrew). The newsletter reported on feminist activities taking place in New Jewish Agenda chapters across the country. But in time, they recognized that they had a broader vision to share with the world—one that would take them beyond organizing within New Jewish Agenda, an organization that folded in 1992 due to internal conflicts (see Nepon, 2012), to found a journal that offered Jewish feminists an ongoing conversation.

Bridges was published biannually from 1990 until 2011. Throughout, Kinberg was its managing editor and only paid employee. While Bridges was a work created in true collaboration among Jewish feminists and their interlocutors, it was nurtured by Kinberg’s commitment to the transformative power of an ever-evolving Jewish feminist discourse, stiched together through caring acts of relation. Bridges was a collaborative project that produced and documented relations among Jewish feminists across countries, languages, and generations. Contributors shared a sense that participation in the production of Bridges was educational and developmental. As one of the youngest editors wrote in her final missive, acknowledging Kinberg’s loving, teacherly style, “I hope more young folks join Bridges, for this increasingly rare on-the-job mentorship, trust/respect and sorority” (Stein 2007). Throughout the publication, the intimacy of relations within the project was palpable.

The readers of Bridges were surprisingly present in its pages. Each issue began with an introduction by Kinberg: warm missives that traced the communications, locations, and lives of the editorial board, usually made up of about eight women. These were followed by letters, many of which included responses from authors, who might be addressed by first name. The letters to Bridges were often critical, taking issue with a particular detail from a text, but they were invariably intimate: letters to the editor were dedicated “Dear Sisters,” “Dear Friends,” “Dear Bridges,” or, signaling a shared effort for what they called the “continuity” of Yiddish, “Dear Yentas.”

When the editors took time to regroup in 1999, they returned to publication with a double-issue that began with an unusually transparent review of the project’s finances, along with a new campaign, “Bridges Campaign 2000,” or “BC2K,” which was an effort to garner community-based funds for the journal’s sustainability (2000). While Bridges eventually had to accept institutional funding and was housed, in its later years, at Indiana University Press, this effort for independent funding provided by community members underscored the journal’s self-definition as a grassroots endeavor, in step with its supporters. When a new member joined the editorial board, or retired her post–or, more intimately, when a close family member of the editorial board died, or when one of them had a baby–Bridges readers knew. This participatory, communicative approach was evidenced throughout the journal: at the back of each issue, a “community bulletin board” announced listservs, conferences, upcoming anthologies, opportunities for funding creative projects, exhibits, events, and community-based research, representing Jewish feminism as a living, participatory movement.

Content and Readership

The first article in the first issue, a work of fiction penned by Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz, announced the location from which Bridges would consistently embark. “Some Pieces of Jewish Left: 1987” (Kaye/Kantrowitz 1990) introduced four women whose dialogue with each other formed the ground for a lived iteration of Jewish feminism, constantly revised and reinvented: Rosa, a red diaper baby who decries her parents’ unconscious racism; grey-haired, older-generation Fran, lifelong citizen of that country called Jewish New York City, who balks at the image of herself as one of “The Jewish People”; Chava, a college student, raised in Yiddishkeit, who is preoccupied with the drama of her parents’ era of 1960s radicalism; and middle-aged Vivian, isolated from Jewish community, and therefore obsessed with Jewishness. These four fictional women—but especially Vivian, who is defined by her experience of cultural estrangement and longing—might represent the passionate readers who would be the biggest fans of Bridges in the following decades, when the journal at its zenith boasted 3,000 subscribers.

Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi women much like Kaye/Kantrowitz’ four characters created the basis and the bulk of Bridges. But like Kaye/Kantrowitz herself, Bridges creators’ desire to claim and honor the survival strategies and life experiences of migration and diaspora edged Jewishness away from the amalgamating forces of whiteness (see Kaye/Kantrowitz 2007). In its insistence on Jewish multiculturalism, Bridges stood against the assimilationist ethos that dominated its geo-historical moment. This anti-assimilationism was showcased in contributors’ engagement with nonwhite Jewish experience, and also in their work to salvage and revive women’s writing in Yiddish, a project that spanned the length of the journal’s publication. In the second issue, Irena Klepfisz, a renowned Yiddishist and member of Bridges’ founding Advisory Editorial Board, inaugurated the decades of work to translate and publish historical Yiddish feminist literature in Bridges. Klepfisz’s work, and that of Yiddish editor Faith Jones after her, powerfully shaped this generation of Ashkenazi Jewish feminism by reconsidering its past. With a column titled “From the Archives,” Bridges exposed an earlier generation of Ashkenazi feminist writing which, without translation, would have remained inaccessible to contemporary readers. This prose, carefully introduced to offer historical context, printed in the original Yiddish followed by English, presented a legacy of Jewish feminist critiques that resist Ashkenazi Jewish patriarchal family and partnership practices and reject leftist masculinism: critiques based in the everyday qualities of ordinary women’s lives.

While Bridges’ authors were predominantly Ashkenazi women, and its readership was as well, the creators of Bridges were committed to expanding their understanding of Jewishness, and of relationships between different Jewish people as well as across Jewish/not Jewish difference, far beyond explorations of their identities as (mostly) Ashkenazi Jewish feminists. The journal often featured the writing of Jewish women of color, Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahim, and non-Jewish people of color—some of whom, like well known lesbian feminists Gloria Anzaldúa and Barbara Smith, served on the journal’s advisory board, as did the non-Jewish white antiracist lesbian feminist Mab Segrest. These collaborations signal the desire for enacting feminist solidarities across difference, and the expansive notion of belonging in diaspora that the journal exemplified.

Showcasing their antiracist and diasporic commitment, Bridges’ 1997 issue on Mizrahi and Sephardi women became the most popular to date (vol. 7, No. 1, Winter 1997). As the editors wrote in their introduction, it was the first collection that they knew of to publish Sephardi and Mizrahi women’s writing. This issue was one of the most geographically diverse; editors noted that the contributors’ “Jewish families are from the Balkans, Egypt, Greece, India, Iraq, Israel, Kurdistan, Libya, Morocco, Yemen, and Turkey” (Crespin and Jacobus, 1997). The issue was replete with critical family histories, poetry, and accounts of cultural practices—food, song, and ritual. It dove into the politics of Mizrahi feminism at the turn of the millenium, with a report from the first feminist Mizrahi conference that highlighted moments of dispute as well as points of unity.

Four years later, in 2001, the issue on “Writing and Art by Jewish Women of Color” continued Bridges’ antiracist work, emphasizing racialized Jewish women’s connections within and across diasporas. The issue featured Black Jewish women’s writing throughout the African diaspora, from accounts of Ethiopian and other African Jewish migration and cultural practice (Benjamin 2001) to one Southern Baptist and Catholic woman’s conversion to Judaism and participation in Yemeni Jewish culture (Hunter Haruach 2001), to a report on the creation of an online community, AfrAmJews, along with a practical guide titled “Jews of African Descent: Getting Started on the Internet” (Ngina 2001). The issue showcased Mizrahi feminist magical realist writing spanning Baghdad and Los Angeles (Levy 2001), a portfolio of art by Mizrahi women exhibiting in a Jerusalem gallery, and a Mizrahi feminist critique of Israeli politics responding to the waning power of the “Peace Camp” (Malekar 2001).

Carrying Across

While the pages of Bridges present an impressive variety of experiences and opinions, with contradictory views and contrasting locations often dynamically placed alongside one another, the journal also held political commitments. Appearing as it did in the midst of rising right-wing authoritarianism and neoliberal restructuring across Jewish diasporic locations, Bridges contested dominant norms that threatened collective survival by offering a space for exploring subjugated knowledge, for making sense of challenging lived realities, and for reclaiming histories vulnerable to erasure. They steeled themselves against the most toxic trends of their times, declaring in their submission guidelines: “We will not publish material that perpetuates anti-Jewish, anti-Arab, sexist, classist, racist, homophobic, ageist, fat-phobic, ablebodyist or other biases which distort our perceptions of each other and hinder alliances” (e.g. vol. 5, no, 1, 1995 p. 123). The loosely interlinked, multiplicitous Jewish feminist perspectives that Bridges foregrounded were announced with intimacy, contravening the dogmatism and fiery manifestos that characterized the radical left in which it participated, offering a more gentle cultural space for antiracist feminist knowledge production. The openness, compassion, and deep listening to which Bridges was committed itself speaks volumes; the work as a whole remained couched in a Jewish feminist history and continuing legacy of leftist internationalism, but the work was tempered and transformed through feminist methods of compassionate listening and capacious relationality.

Consonant with the women of color feminist literature from which the journal took its cue, ranging from the paradigmatic This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1981) to the youthfully rebellious Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism (2002), Bridges entered the field of identity writing to reckon with Jewish women’s uncomfortable differences and fruitful interrelations—with others, as well as with each other. In 1991, the working-class writer tova stabin joined the editorial board and experienced isolation in her focus on class difference. She initiated a process through which the editorial board was asked to address issues of class, which proved to be a struggle and point of growth for some (Kraut and stabin 2011). “Working Class Words,” stabin’s long-term project, became a frequent section of the journal. Contributors to the column contested the stereotype that casts all Jewish people as wealthy, offering space for Jewish feminist exploration of working-class experience, mostly in short memoir form. And yet, twenty years later, stabin still felt that Bridges’ effort to address working-class experience, and class inequality, was incomplete: “we began to deal with class, but didn’t go deep enough or far enough or keep at it,” she mused upon the journal’s close (ibid).

While engaging charged themes of class and race, Bridges refused binaries, productively querying rather than dictating whether and how such systems of power, and lived experiences of religion, language, heritage, politics, or geographic location, defined Jewishness in contemporary feminist culture and knowledge production. Given the growing normalization of Zionism in Jewish communities across the United States in the late twentieth century, one unusual set of differences the journal represented was the dizzying variety of Jewish feminists’ understandings of Zionism and Palestine, which Bridges featured constantly; every issue offered perspectives on the Jewish state-national project and Palestinian oppression. As with other themes in Bridges, an approach to discussion of Zionism was not prescribed, and both Zionist and anti-Zionist perspectives, among other explorations of the state of Israel, were represented. Eschewing the dichotomy of colonizer and colonized, the journal sought voices that would interrupt the conflict with forms of convergence and dissension unmappable on a bifurcated chart. For example, when the Likud Party narrowly achieved a victory, installing Benjamin Netanyahu as Prime Minister of Israel, Kinberg wrote of the editors’ “hope that the election results will in fact galvanize progressive forces in Israel and strengthen common ground with Palestinians in a quest for just peace” (Bridges vol. 6, no. 1, 1996). Kinberg’s note on the potential for “common ground” with Palestinian people fell alongside the words of Israeli women, often the most vocal opposition to simplistic American Jewish feminists’ idealizations of the state-national project. The most conflicting perspectives, from strident Zionism to calls for Jewish feminist solidarity with Palestine, were both expressed in explicitly feminist terms; when Ms. Magazine refused to print an advertisement touting the Israeli state as a fundamentally feminist project, contributing writer Michelle Alperin deftly explored the many contrasting perspectives on this incident in an extended essay that offered Jewish feminists in the United States rare insight into perspectives on feminism and nationalism across geographies (Alperin 2008).

Addressing the gap between Israeli and non-Israeli Jewish feminist understandings of Palestine during the Second Intifada, founding co-editor and frequent contributor Adrienne Rich took a moment to define a term that was core to the journal’s mission: “trans-lation: literally, carrying across” (2002). Translation was so frequent in Bridges, so central to its development of diaspora consciousness, that one special edition was dedicated entirely to the theme, titled “The Bridge of Translation.” (Jones 2009). Yiddish, Hebrew, Ladino, French, Hungarian, German, and more rarely, Arabic and Aramaic: intertwined tongues, Jewish feminist words. Rich’s “carrying across” a bridge of translation is one of innumerable moments when Bridges juxtaposed perspectives across language, region, ideology, and practice. The renowned poet, essayist, editor, and activist meditated upon this concept in the midst of an epistolary correspondence between herself—a Jewish American lesbian feminist—and an Israeli feminist professor, Lois Bar-Yaacov, with a dialogue that began in Bridges' letters to the editor. The exchange, exemplary of Bridges’ representation of communication across complex difference, framed two Jewish feminist poets’ divergent views on Jewishness, national identity, and Israeli state practice, a dialogue via translation: deep listening without enemyship, unity, or consensus.

Saying Goodbye

With an editorial board that brought the politics of lesbian feminist identity work to the social and cultural development of diasporic belonging, Bridges became a remarkable space for the exploration and support of Jewish women’s diversity. It is an archive of complex interrelation, where vastly varied life experiences and perspectives appear adjacent, in direct or indirect dialogue. Over twenty-one years of publication, Bridges went from an activist newsletter, to an independently produced feminist rag, to a literary journal published by a university press. As Kinberg wrote to readers in the final Letter from the Editor, when Indiana University chose not to renew the publishing contract, she declined to continue the work, daunted by a return to grassroots fundraising. Besides, by then, Kinberg recalls, “an explosion of Jewish feminist and progressive blogging and other uses of social and electronic media” offered many new options for Jewish writers. Still, she added, “nothing has filled Bridges’ political space... but lots of new spaces have been created” (Kinberg, 2011).

Bridges’ final issue offered a quintessential distillation of its work through conversations among Jewish feminist writers: bridges made of words that revealed, as Kinberg noted, the ubiquity of the fundamental feminist trusim “the personal is political” (Dubovsky, 2011). As the journal’s mission statement declared, from the feminist, lesbian, and gay movements, its commitments remained in “integrating analysis of class and race into Jewish-feminist thought and to being a specifically Jewish participant in the multi-ethnic feminist movement.” In doing so persistently for more than twenty years, Bridges enlarged the possibilities for Jewishness, for feminism, and indeed, for the values of tikkun olam, “repair of the world,” that its many creators and contributors so clearly cherished.

Alperin, Michelle. “An Image of Israel: Jewish Feminists Discuss Ms. Magazine vs. American Jewish Congress.” Bridges vol. 13, no. 2, 2008.

Atkin, Ruth, et. al. “From the Editors,” Bridges vol. 1, no. 1, 1990.

Benjamin, Siona. “Belaynesh Zevadia: Israeli, Ethiopian Diplomat.” Bridges vol. 9, no. 1, 2001.

Crespin, Debra and Sara Jacobus. “Sephardi and Mizrahi Women Write About their Lives: Introduction.” Bridges vol. 7, no.1 1997-98.

Dubofsky, Chanel. “Bridges, a Jewish Feminist Journal, Says Goodbye.” The Forward, June 16, 2011.

Hunter Haruach, Miri. “Born to be Yemenite.” Bridges vol. 9, no. 1, 2001.

Jones, Faith, ed. “Special Edition: The Bridge of Translation.” Bridges vol. 14, no. 2, 2009.

Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie. The Colors of Jews : Racial Politics and Radical Diasporism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Kaye/Kantrowitz, Melanie. “Some Pieces of Jewish Left: 1987.” Bridges vol. 1, no. 1, 1990.

Kinberg, Clare. “From the Editor.” Bridges, 2011.

Kraut, Ruth and tova stabin. “Class Words.” Bridges Vol. 16, No. 1, Spring 2011.

Levy, Lital. “Conversations with a Jinni.” Bridges vol. 9, no. 1, 2001.

Lober, Brooke. Personal correspondence with Clare Kinberg, 2021.

Malekar, Molly. “The Compass of Human Conscience: Notes on the Israeli Peace Camp, May 2001.” Bridges vol. 9, no. 1, 2001.

Nepon, Ezra Berkley. Justice, Justice Shall You Pursue: A History of New Jewish Agenda. Philadelphia, PA: Thread Makes Blanket Press, 2012.

Ngina, Tamu. “AfrAmJews Forum: Creation of an Online Community” and “Internet Resources on Jews of African Descent.”

Simons, Shoshana. “Searching for Fritada.” Bridges vol. 7 no.1, 1997.

“Smoke of the Battle.” Words and music by Laura Wetzler. Bridges vol. 1, issue 1, 1990.

Stein, Jessica. “The Ongoing Job of the Artist-Activist: A Brief Goodbye from Jessica Stein,” Bridges vol. 12, no.1, 2007.

“Two Prayers.” Words and music by Carole Rose Livingston. Bridges vol.1, issue 1, 1990.

“Two Trees.” Words and music by Rita Falbel. Bridges vol. 1, issue 1, 1990.