Dinah: Bible

The story of Dinah, the only daughter of the patriarch Jacob, recounts an episode in which she goes out to see the “daughters of the land” but is raped, seduced, and/or abducted by Shechem, a Hivite prince, who subsequently falls in love with and wishes to marry her. While her father is silent, Dinah’s brothers negotiate marriage terms in guile. After all the male residents of the town circumcise themselves (a precondition for intermarrying with Jacob’s family), Simeon and Levy slaughter all the men and rescue Dinah from Shechem’s house. The various responses to the daughter’s debasement—the residents of Shechem, Jacob’s, the brothers’, and even Dinah’s silence—suggests a multivocal composition which centers on the question of intermarriage with the native “Canaanites” of the land.

Dinah’s Debut and Disappearance

Dinah is the only daughter of the patriarch Jacob—at least the only one named (others are mentioned in Genesis 37:35 and 46:15, perhaps including granddaughters). Her mother Leah bore her after six sons and named her “Dinah” (30:21), meaning “her judgment,” although no explanation for her name is given in the biblical account (in contrast to the naming of sons).

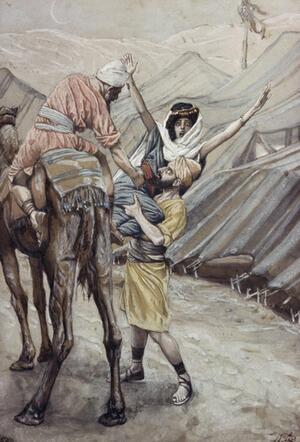

The story of Dinah recounts an episode in which the girl (or young woman) goes out to see the “daughters of the land” (34:1) but is raped, seduced, and/or abducted by Shechem, a Hivite prince, who subsequently falls in love with her. Shechem asks his father, Hamor, to negotiate marriage terms. Jacob is silent on the matter, but Dinah’s brothers are distressed by the “outrage, for such a thing is not done to a daughter of Jacob” (v. 7). They demand that Shechem and all the males of the town circumcise themselves before intermarrying with Jacob’s family—a proposition made in guile. The residents of Shechem agree, presuming they will collectively gain both wealth and women by the deal. But on the third day, when all the male residents are in dire pain from the circumcision, Simeon and Levi (full brothers of Dinah) enter the town, slaughter all the men, and rescue Dinah from Shechem’s house (v. 26). The other brothers then pillage the town in revenge for the defilement of their sister (v. 27). Jacob is displeased, for now he has become odious to the natives of the land, but the brothers are given the last word: “Should our sister be treated like whore” (v. 31).

With the exception of the opening verse, Dinah is wholly passive in the story; she is acted upon and given no voice. After she returns to her father’s household, she is never heard of again in the biblical narrative, though she is mentioned along with the 66 descendants of Jacob who go down from Canaan to Egypt (46:15).

Raped or Debased?

The story has been called “The Rape of Dinah,” although not all scholars agree that she was raped—forced into sexual relations against her will. Unlike in the account of the rape of Tamar by her half-brother, Amnon (2 Samuel 13:12-14), we do not hear Dinah speak or cry out in resistance before Shechem takes her. Further, while Amnon violently overpowered Tamar despite her pleas of protest, it is not clear that Shechem forced himself upon Dinah; rather “he took her, lay with her, and debased her [‘inneha]” (Genesis 34:1).

In the biblical world of the Ancient Near East, when a virgin had sex out of wedlock—whether seduced or raped—she was devalued in terms of her social status, bringing shame upon the family. Her virginity was crucial in negotiations over bride-price and the familial alliances forged through marriage. In the legal discourse around sexual intercourse with a virgin outside of wedlock, whether she was betrothed to another man or not, the woman was presumed to have consented if she did not cry out in protest in the city or town, and to have been raped if she was taken in the open country where her cries could not have been heard (Deuteronomy 22:23-29). The woman’s will or testimony was simply not taken into account.

Given that Dinah was taken in the open country, her father and brothers presumed she had been raped, as the parallel terms suggest: she was “defiled” (Genesis 34:5, 13, 27); treated “like a whore” (v. 31); it was deemed an “outrage” (v. 7; see Deuteronomy 22:21, Judges 20:6 and 10; 2 Samuel 13:12). Whereas the seducer or rapist would normally be forced to pay the virgin bride-price for the daughter and marry her (Deuteronomy 22:29, Exodus 22:15-16), Dinah’s brothers negotiate terms with Shechem and his father disingenuously, with no intention of sanctioning the marriage. The story then may be read as a polemic against inter-marriage, where the abduction of Dinah becomes the pretext for the severance of ties with Shechem and the Hivites, one of the Canaanite tribes.

The Multivocal Nature of the Story

The narrative, however, is rife with gaps and ambiguities, in which Dinah’s silence and the divide between father and brothers loom large. First, the reader’s sympathies turn to Shechem even though he may have forced himself upon Dinah. After sexual relations, “his soul clung to Dinah, Jacob’s daughter, he loved the girl and he spoke to the girl’s heart” (Genesis 34:3). In contrast to Amnon after the rape of Tamar, who banishes her when his hatred for her exceeded the “love” he had felt (2 Samuel 13:15), Shechem desires to marry Dinah. The expression “speak to the heart” implies a desire to ingratiate oneself after a breach (as in Genesis 50:21, Judges 19:3, Ruth 2:13, Hosea 2:16). Further, he so “desired her” (v. 8) that he was willing to pay a very high bride-price to find favor in the eyes of the family (vv. 11-12). While the residents agree to circumcise themselves because they stand to gain not only women but a great many livestock (v. 23), Shechem seems genuinely emotionally attached to Dinah. This makes the brothers’ deceit and wholesale slaughter all the more heinous. Further, Jacob keeps silent and remains passive throughout the negotiations; the reader does not know whether he approves of the marriage proposal. After the rampant bloodshed and sack of Shechem, the patriarch denounces his sons, Simeon and Levi, for stirring up trouble for him and “making him odious among the natives of the land, the Canaanites and Perizzites” (v. 30). He will now live in fear of retaliation and, despite having bought land near Shechem with the intention of settling down (33:19), he must move on. Later he curses Simeon and Levi as “instruments of violence” (Gen. 49:5-7)—neither tribe inherits territory with definitive borders in the land. The sympathetic depiction of Shechem and Jacob’s opacity suggest the outcome might have been different had the brothers not taken matters into their own hands, avenging their sister’s abduction with mass slaughter.

The Polemics Underlying the Story

The story of the “‘rape” of Dinah, as an Israelite foundational narrative, presents the impossibility of integration with the Canaanites in the land. The boundaries of identity are forged through negotiations over the destiny of the young woman’s body. The final rhetorical question of the chapter is posed by the brothers: Is Dinah “to be treated as a whore [zonah]?” (v. 31). That is, can she be allowed to be taken out of wedlock—“defiled” or “debased”—by the “sexually depraved” foreigner? In the context of the honor-shame socio-cultural milieu, the daughter’s voice hardly matters. Even when the Hivites are willing to remove the Israelite symbol of “disgrace” (the foreskin) from their male bodies in order to intermarry with Jacob’s family, their status as the tainted ineluctable “other” remains.

While set in the patriarchal period (circa 1800 BCE), the story was most likely composed much later, when the issue of intermarriage between Jacob’s descendants and the Canaanites was no longer an issue. Some scholars claim that it was composed during King Josiah’s religious reforms (7th century BCE); others suggest the early Second Temple Period of Ezrah-Nehemiah, when the concern with endogamy (“marriage out”) was paramount (similar to that found in Deuteronomy 7). Others argue that the people of Shechem were prototypes for the Samaritans, a people nominally identified with Israel before the Babylonian exile, but excluded from allying with the Jews upon their return to Zion (circa 5th century BCE).

Contemporary feminist readers seek to reclaim the voice of the silenced Dinah, to reassert her own agency and even desire to be with Shechem (as in the Anita Diamant’s novel, The Red Tent). Alternatively, if she was raped, her own pain and anguish must be heard over the violent clamor in defense of male honor.

Amit, Yairah. Hidden Polemics in Biblical Narrative, trans. Jonathan Chipman. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2000, 189-217.

Bechtel, Lyn. “What If Dinah Is Not Raped? (Genesis 34).” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 62 (June 1994): 19–36.

Berlin, Adele. “Literary Approaches to Biblical Literature: General Observations and a Case Study of Genesis 34.” In The Hebrew Bible: New Insights and Scholarship (Jewish Studies in the 21st Century), ed. by Frederick E. Greenspahn. New York: New York University Press, 2007.

Dolansky, Shawna. "The Debasement of Dinah." TheTorah.com (2015). https://thetorah.com/article/the-debasement-of-dinah

Joseph, Alison L. "Who Is the Victim in the Dinah Story?" TheTorah.com (2017). https://thetorah.com/article/who-is-the-victim-in-the-dinah-story

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. “Virginity in the Bible.” In Gender and Law in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East, edited by Bernard M. Levinson, Tikva Frymer-Kensky, andVictor H. Matthews, 79-96. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998.

Scholz, Susanne. Rape Plots: A Feminist Cultural Study of Genesis 34. New York: Peter Lang, 2000.

Zlotnick, Helena. Dinah’s Daughters, Gender and Judaism from the Hebrew Bible to Late Antiquity.(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002, 33-48.