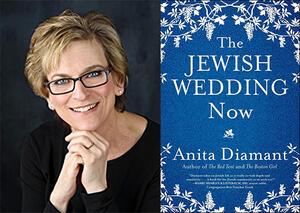

An Interview with Anita Diamant

As wedding season kicks into high gear for rabbis everywhere, I’d be lost without The New Jewish Wedding, which has just been revised for the third time.

Once, I gave a copy to some family friends who weren’t even sure they identified as Jewish. After reading Anita Diamant’s book, they called and asked if we could do a Brit Ahuvim ceremony, a feminist egalitarian alternative to Kiddushin found in the book’s appendix. I was so excited by their interest in the book that I agreed to do their wedding on the spot!

The latest edition, The Jewish Wedding Now, came out this month, and I was delighted to interview Diamant after hearing her speak to the Women’s Rabbinic Network at our biennial convention.

What sparked your interest in writing books about the Jewish life-cycle?

When I was getting married, the book I needed did not exist. When I had a baby, there really was nothing about welcoming ceremonies for girls, and no real discussion about brit milah. There were holes on the bookshelves, both for me and my cohort. As a journalist, I had the skills to fill them.

The first two editions were called The New Jewish Wedding. Why is this book called The Jewish Wedding Now?

When the first edition came out 1985, it was definitely a new way of looking at tradition, through a contemporary lens, through a feminist lens. But that's not new anymore. We have people who are approaching our tradition creatively and exploring the traditions of the past.

These books have never been about telling people what to do. They are a reportage that describes contemporary practices. While in terms of Jewish history, 32 years is the blink of an eye, the changes have been profound, both in the Jewish community and in the larger society. The “now” in the title puts the conversation more in the present rather than reflecting backwards.

You've changed how gendered language is used in this book. What was that process like?

It was much easier than I thought it was going to be. I substituted “couples” or “beloveds” for “brides” and “grooms,” except when I was discussing ancient tradition. I changed the pronouns “him” or “her” to “they.” At first, the lack of grammatical agreement really bothered me. But I'm over it. My discomfort certainly had nothing to do with the politics of it, I was fine with that. And I hated writing “his/hers,” so this was an elegant solution. It also reflects the way that the liberal Jewish community is talking in the “now.”

How does this new edition address LGBTQ Jews and their needs differently from the last one?

For my first book, I asked my editor if I should write a paragraph about same-sex couples. My editor said no. The phrase “marriage equality” didn’t even exist in 2001 (when the book was last revised), so the conversation was about commitment ceremonies. Same-sex weddings were still uncommon. I explained how couples have to find a rabbi who will treat them with respect. In this book, there isn’t even a separate section about same-sex weddings. Now there is one big chuppah that includes same-sex couples, couples where one person identifies as Jewish and one doesn't. Jewish weddings are not one size fits all, but the questions are the same for everybody. It’s important to find someone who is delighted to do your wedding. Each couple has their own “stuff,” and they need to have chemistry with their rabbi.

I know you've been passionate about meeting the needs of interfaith families. What has changed for interfaith families, and how is that reflected in the book?

In 1985, it was impossible to find a rabbi who would co-officiate or officiate at an intermarriage. Now we have Interfaith Family and so many more resources. You can more easily find a place for yourself where you are really welcomed and embraced. There is a sense in the liberal Jewish community that you are no longer alone, we're not just tolerating you, we’re delighted that you’re here. Many of the barriers are internal now: feeling like a fraud, worrying about how you will fit in as a technically not-Jewish person. But there is more recognition that nearly everyone has someone in the family who is intermarried. I'm afraid that sometimes the powers that be don't acknowledge that. We need them to recognize that this is us. This is who we are.

How has the role of the rabbi changed since you last revised the book and how did you address that?

I didn't talk to my peers when I wrote this edition. I talked to younger rabbis and outliers. They all told me: You really have to say why you need a rabbi. In today’s DIY culture, it’s all about you and you can do whatever you want. It’s not an automatic thing to call the rabbi. People get ordained or get credentials for the day.

The relationship between rabbis and couples is complicated in new ways now, but it’s never been more important. The power structure is different. Couples want more of a peer-to-peer experience with their rabbi. Their wedding may be the first time connecting with Judaism, either ever or since b'nai mitzvah, camp, confirmation, or college. It’s not always perfect, but if you can find a rabbi who listens to you, teaches you, and connects with you, that’s a powerful opportunity.

Who are you hoping will read this book and why?

I’m reaching out to the same people I was with the first book. I hope that rabbis will give it to couples, and couples will find it intriguing. I hope it will still be a way of saying to your mother, "See, I don't have to have a receiving line!” I want to provide a space for people to have a debate about what's really Jewish, what's permitted, and what's possible. I hope that it opens a conversation for people of all descriptions and backgrounds. When that happens it makes me very happy.

Is there anything else you want to tell us about this book?

We need Judaism to be a culture of yes. That's the philosophy behind Mayyim Hayyim and a new approach to mikvah. It’s a way to introduce someone to the beauty of Jewish ritual. There was a study at the Cohen Center at Brandeis that Jewish officiation at an interfaith marriage means that the couple is three times more likely to raise their children Jewish. If you can say yes, you have to say yes, because it's an opportunity to make a connection that's personal. People go "all in" because of their relationship with us. Saying yes means betting on the future.

hi Anita, It's your cousin David here. Yes I do agree with you that DIY is the way things are going man and then the one married by a family friend Jim and I were married by my son Matthew .when Beth and I married we use the rabbi that we never had met. When Fred and I were nine years old my mom placed us in an Orthodox yes Shiva school in Williamsburg Brooklyn. It was a horrible experience We were told to spit on the ground past A church. You are rewarded with Candace if we prayed for another hour on the Sabbath. Yet I know Mary Beth was completely non-religious I kept up all the dishes of the holidays and the songs that I had memorized Many Jewish songs which Matthew has learneda long time as well as tmy grandchildren and Linda as well!