Asenath: Midrash and Aggadah

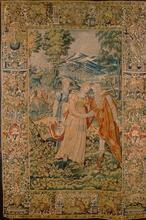

Joseph meets Asenath (Asenath throws the Idols out of the Tower), Brussels 1490-1500, artist unknown. Source: Bodes Museum Berlin, via Wikimedia Commons

There are two approaches to the issue of Asenath’s descent in the Rabbinic texts. One view presents her as an ethnic Egyptian who converted in order to be married to Joseph, joining a series of positive examples of women converts in the Bible. The second approach argues that Asenath was not an Egyptian by descent, but was from the family of Jacob, directed by God to end up in Egypt so that Joseph would find a suitable wife from among the members of his own family. In either case, Asenath is accepted as part of the family and her sons are accepted as worthy descendants by Jacob.

Asenath is mentioned in the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah as “the daughter of Poti-phera” (Gen. 41:45), who was married to Joseph in Egypt. The Rabbis found it difficult to accept that Joseph, who withstood the wiles of Potiphar’s wife and proclaimed his loyalty to the Lord in the palace of Pharaoh, would marry a non-Israelite woman. The question of Asenath’s origins has significant consequences for the standing within the Israelite tribes of Manasseh and Ephraim, the two sons born to Asenath and Joseph.

There are two Rabbinic approaches to the issue of Asenath’s descent. One view presents her as an ethnic Egyptian who converted in order to be married to Joseph. She accepted the belief in the Lord before she was married and raised her children in accordance with the tenets of Judaism. The second approach argues that Asenath was not an Egyptian by descent, but was from the family of Jacob. God directed matters so that she would end up in Egypt, so that Joseph would find a suitable wife from among the members of his own family. Accordingly, Ephraim and Manasseh are worthy descendents, who continue the way of Jacob.

Asenath the Convert

The traditions that maintain that Asenath was a convert present her as a positive example of conversion, and include her among the devout women converts: Hagar, Zipporah, Shiphrah, Puah, the Daughter Of Pharaoh, Rahab, Ruth and Jael (A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash Tadshe, Ozar ha-Midrashim [ed. Eisenstein], p. 474). The Rabbis learn from Joseph’s marriage to Asenath that a favorable attitude is to be exhibited to converts, who are to be drawn closer. Thus, Joseph married Asenath daughter of Poti-phera, and Joshua son of Nun, who was a chieftain of the tribe of Ephraim (Num. 13:8), would be descended from this union. The midrash adds that Joseph’s behavior served as an example for both Joshua and David, when they acted charitably with the Gibeonites and drew them closer to Israel (Midrash Samuel [ed. Buber], 28:5, based on Josh. 9 and II Sam. 21:1–9). An additional midrashic dictum notes a number of converts who became members of the families of the righteous leaders of Israel. Thus, Joseph married Asenath, Joshua wed Rahab, Boaz took Ruth for a wife, and Moses married the daughter of Hobab (= Jethro) (Eccl. Rabbah 8:10:1).

Asenath the Daughter of Dinah

The traditions that trace Asenath to the family of Jacob relate that she was the daughter born to Dinah following her rape by Shechem son of Hamor. Jacob’s sons wanted to kill the infant, lest it be said that there was harlotry in the tents of Jacob. Jacob brought a gold plate and wrote God’s name on it; according to another tradition, he wrote on it the episode with Shechem. Jacob hung the plate around Asenath’s neck and sent her away. God dispatched the angel Michael to bring her to the house of Poti-phera in Egypt; according to yet another tradition, Dinah left Asenath on the wall of Egypt. That day Poti-phera went out for a walk near the wall with his young men, and he heard the infant’s crying. When they brought the baby to him, he saw the plate and the record of the episode. Poti-phera told his servants, “This girl is the daughter of great ones.” He brought her to his home and gave her a wet nurse. Poti-phera’s wife was barren, and she raised Asenath as her own daughter. Consequently, she was called “Asenath daughter of Poti-phera,” for she was raised in the home of Poti-phera and his wife, as if she were their own daughter. This narrative teaches that all is foreseen by God. Each of Jacob’s sons was born together with his future spouse, except for Joseph, who was not born together with his mate, since Asenath daughter of Dinah was fit to be his wife. God directed matters so that Joseph would find a wife when he went down to Egypt, and Asenath was suitable for him (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer [ed. Higger], chaps. 35, 37; Midrash Statements that are not Scripturally dependent and that pertain to ethics, traditions and actions of the Rabbis; the non-legal (non-halakhic) material of the Talmud.Aggadah [ed. Buber], Gen. 41:45).

Asenath as Part of the Family

Gen. 43:24–34 relates that Joseph invited his brothers to eat with him when they went down to Egypt to procure food. In the midrashic depiction, this was a family meal in which Joseph’s wife and children also participated. Joseph sat his brothers before him, “from the oldest in the order of his seniority to the youngest in the order of his youth” (v. 33), and brought the portions to the meal. Joseph gave each one, including Benjamin, his portion, and then he took his own portion and gave it to Benjamin. Asenath took her portion and gave it to Benjamin, as did Ephraim and Manasseh. Thus, there were five portions next to Benjamin, as is recorded in v. 34: “But Benjamin’s portion was five times that of anyone else” (Tanhuma, Vayigash 4). The verse then continues: “And they drank their fill with him,” on which the midrash comments that all those years during which Joseph had not seen his brothers, he did not imbibe of wine, nor did his brothers until they saw him; now they drank with him, to intoxication (Gen. Rabbah 92:5). In these midrashim, Asenath and her children shared Joseph’s sense of loss all the years that he lived apart from his family, and they also participate in the excitement and joy when he is reunited with Benjamin, his only maternal brother.

The Torah relates (Gen. 48) that when Jacob was old and infirm, Joseph came to visit him, together with his two sons Manasseh and Ephraim. Jacob blessed Joseph’s sons and declared that, for him, they were equal to his own sons and they would receive a double land portion. The midrash describes the soul searching that accompanied this decision, which was connected to Joseph’s marriage to Asenath. According to one tradition, when Jacob saw Joseph’s sons and wished to bless them, the Shekhinah (Divine Presence) departed from him. Jacob thought that Manasseh and Ephraim were not the sons of a legitimate marital union, and were therefore unfit to receive a blessing. Jacob asked (v. 8): “Who are these?”, that is, how were these born? (Midrash Aggadah [ed. Buber] 48:8). In another tradition, Jacob saw with the spirit of divine inspiration that Jeroboam son of Nebat, an Ephraimite, would erect (statues of) calves, incite Israel to engage in idolatry, and cause 500,000 of Israel to fall in a single day (as is related in II Chron. 13:17). Jacob therefore asked: “Who are these?”—perhaps you improperly married the mother of these? Joseph brought before him Asenath and her ketubah (marriage contract) and said (Gen. 48:9): “They are my sons, whom God has given me here [ba-zeh, literally, with this]”: “with this”—with a ketubah and proper marriage. He also showed him that, just as he was circumcised, so were his sons (Midrash ha-Gadol, Vayehi 48:8–9 [ed. Margaliot], pp. 820–21). In another midrashic unfolding, Joseph began his request by saying: “Father, my children are righteous like me.” He brought their mother Asenath before his father and said: “Father, please, even if only on behalf of this righteous woman.” When Jacob saw this, he told Joseph (Gen. 48:9): “Bring them up to me that I may bless them.” Joseph brought them to his father, who began to embrace and kiss them, and rejoiced in them (Pesikta Rabbati [ed. Friedmann (Ish-Shalom)], chap. 3, fol. 12a).