No Education Without Representation: Recognizing Women in Jewish Texts

I have attended Jewish schools my entire life. This means that from the tender age of six years old I was surrounded by Torah study. From learning how to say the Shema in kindergarten to deciphering sugyot in my tenth grade Talmud classes, Jewish studies have been a huge part of my education. And yet in all these stories that were instilled in me, that were meant to teach me how to be a Jewish person, I never felt represented because of how saturated they are with men.

Adam, Abraham, Yitzchak, Yaakov, Moshe, Aharon, Yehoshua, King David, and so on and so on. Every day of elementary school, I entered class and heard about these same men again and again. We learned who they were, what their connection was to God, and what lesson we should learn from their stories. They were the cornerstones of Judaism, the role models we were meant to follow.

These are the characters who represented the values of our religion, according to my teachers. But where are the women in these stories? The stories of women had so much untapped agency and nuance that we never discussed in my classes. Those were always the stories that piqued my interest. Why didn’t we focus on the difficulties that Sarah faced during her infertility or how Dinah was captured in war? Why wasn’t it highlighted that Rivkah had been the one to encourage Yaakov to trick his father to take his brother’s birthright? Even when discussing Chava (or Eve), the literal first woman in the world, she was always talked about as an afterthought. She was just the accompaniment of Adam, she was created from a man, not in the same image of God as he had been. And when she bit into the fruit from the tree of life, it was simply taught to be an act of weakness, with no time being given to discuss why she did it. Why are these women, who had so much narrative agency and impact, barely discussed?

Instead, these women were, and still are, pushed to the side, overshadowed and overlooked, only brought up in relation to their sons or husbands. They were the mothers and wives of the founders of our religion but never elevated to that status themselves. And when we were taught about female-centered stories, in which they existed separated from men, it was only for the briefest of moments: A week discussing Esther for Purim, a day talking about Rachel and Leah, a few minutes on Moshe’s mother and Miriam.

Growing up with such a male-centered narrative, I felt as if there was no space in Judaism for me. After all, in all the stories I was shown, it was the men who spoke with God and led the tribes. It was the names of the twelve sons of Yaakov I had to memorize for my tests, while Dinah remained absent. The boys sitting beside me in those classes were the true inheritors of the covenant, not me. They were the ones obligated by all the 613 mitzvot, not me.

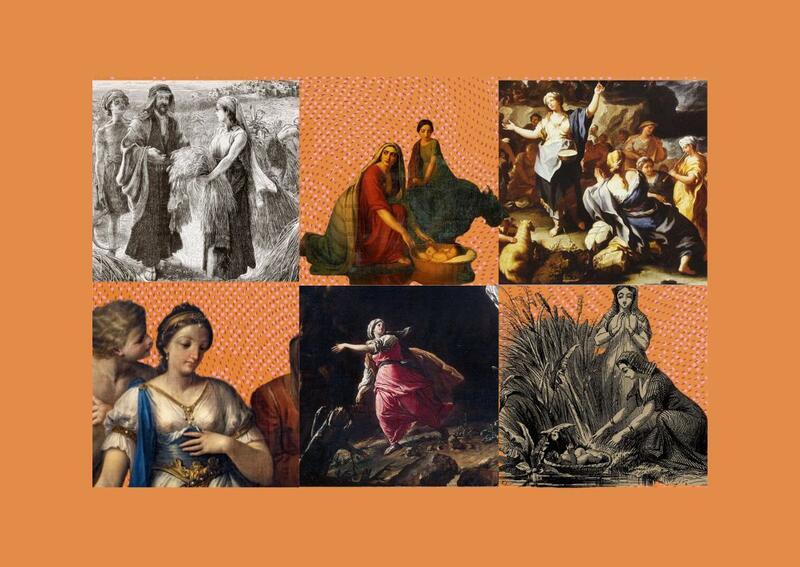

As I got older, I took it upon myself to deepen my appreciation for the imahot (i.e. foremothers, Sarah, Rivka, Rachel, and Leah) I grew up with, and to seek out any female narrative in the Tanakh that I could find. As I read their stories, I was able to see how I fit into the Jewish world. I found strength and pride in the story of Judith and Holofernes, as she saved her city from siege. In Megillat Ruth, I was inspired by the deep admiration and love shared by Ruth and Naomi, as it reflected my own love for the women in my life. I read midrash and commentary about Lilith and Chava (Eve) that explored their lives beyond their role as Adam’s wives.

To me, these women represented what it means to be Jewish. I wanted to embody the strength of Judith, the compassion of Ruth, the intelligence of Rivka. Their stories had just as much significance as those of the men. However, it angered me that it took so long to find them or to see their stories as whole, not just the parts of their stories centered around men. I shouldn’t have had to find them myself; their stories should have been in my curricula as well.

Education is one of the most important parts of a child’s life. It informs how they see the world, themselves, and others in it. And a Jewish education informs how Jewish children see themselves in Judaism. When you don’t have a sense of representation in the material you learn, you feel less of an ownership of it. Therefore, Jewish educational institutions (and especially elementary schools) must be gender-inclusive in their teachings of text, so everyone can feel a sense of ownership over the material.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.