Bilhah and Zilpah Made Me Yearn for Torah

I first became conscious of Bilhah and Zilpah not from Torah, but from reading The Red Tent by Anita Diamant. The book opens with this passage: “We have been lost to each other for so long. My name means nothing to you. My memory is dust. This is not your fault, or mine. The chain connecting mother to daughter was broken and the word passed to the keeping of men, who had no way of knowing. That is why I became a footnote…”

This modern midrash creatively reimagines Dinah’s story not as rape, but as a love story with Shekhem. We meet Dinah, the daughter of Leah and Yaakov. Dinah introduces us to all four of her mothers, including Zilpah and Bilhah, the enslaved women given by Lavan to his daughters, Rachel and Leah, on their respective wedding nights to Yaakov.

I didn’t realize how strongly I needed to hear the voices of women in our biblical narratives. These vivid vignettes of the lives of women made me want to read Torah rather than feel I had to.

The Torah holds thirteen lines that mention Bilhah and eleven that mention Zilpah (and five that name both). Through the story, Bilhah is referred to as שִׁפְחָה shifcha (slave), אָמָה ama (concubine), אִשָּׁה isha (wife), and פִּילֶגֶשׁ pilegesh (concubine), while Zilpah transitions between shifcha, isha, and ama. Bilhah and Zilpah’s voices are completely absent in these lines; they are only spoken about.

The Torah tells us that the enslaved women were owned by Lavan and later given to his daughters, Rachel and Leah, as bridal gifts. They were given away again by the daughters to their husband Yaakov to orchestrate the conception of children that Rachel and Leah would claim as their own.

Midrash adds that Bilhah and Zilpah were themselves the product of a union between Lavan and another enslaved woman, making Bilhah and Zilpah Lavan’s daughters, and sisters to Rachel and Leah. There are scant explicit details on these characters. We don’t know their origin or end story, how old they are in the story, how they or their mother became enslaved, how they met Lavan, how long they lived, who they loved, what they envisioned for their lives, or how they navigated maintaining their relationship with their children (despite the Torah’s language that their children would belong to Rachel and Leah).

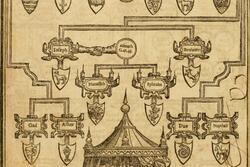

We are more than our circumstances. Bilhah and Zilpah were more than enslaved people, used as a sexual commodity. Ultimately, they raised Dan, Naphtali, Gad, and Asher—and probably all of the family children fathered by Yaakov—as their own, and in doing so were likely responsible for important household functions. Bilhah and Zilpah were multidimensional women who found ways to navigate the realities of their lives. They were women who existed within relationships and left legacies. I am endlessly fascinated by exploring the dynamics between Bilhah and Zilpah (individually and as a unit), and with characters like Rachel, Leah, Yaakov, Lavan, Dan, Reuven, Dinah, and other unnamed women and enslaved people in their encampment—not to mention all the other characters Bilhah and Zilpah may have encountered in their traveling, dwelling, and working.

My interest in Bilhah and Zilpah has grown as they have become a lens through which I can explore slavery, human hierarchies, belonging, disenfranchisement, and fucked-up family dynamics in Torah. In my studies, I’ve also come to appreciate how these topics continue to echo throughout history up to the present. Just as marginalized people are erased today, I had not realized Bilhah’s and Zilpah’s invisibility within their narrative—how little we really “see” them, including in feminist biblical commentary, even as we read their names (which is a feat in itself, merely to be a named woman in the Torah). The cumulative effect of the absence of women’s and marginalized character’s voices made me feel like I was not part of the story—my story.

I relate to Bilhah and Zilpah for the ways their experiences align with my own, of not having autonomy over my body, being named and categorized by others, having my voice silenced, and feeling invisible in plain sight. There is a rich legacy of wisdom from Black Liberation theology and Jewish communities of color: The Combahee River Collective Statement by Black feminists actively resisting racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression and developing integrated analysis and practice of interlocking oppressions; the abolitionist writings and work of living prophet Angela Y. Davis; the history of Callie House’s efforts for ex-enslaved pension thwarted by federal agencies; and many many more. These people and their words give voice to the power of Black feminist resistance in the United States of America. And Rebecca Kuss’s haunting piece Asian Jews Are Hurting, We Need You To Listen is a raw blessing of honest humility that reflects how parts of our community are actively erased through the danger of a single narrative.

I thought with our annual reading of the Torah, one of these years, one of the Jewish communities I am part of would choose to focus on Bilhah’s and Zilpah’s stories through their eyes, but it feels like that day will never come. They seem relegated to stay in the obscurity of zero-dimensional supporting characters who exist solely to add depth to the main characters.

Eventually, I realized I didn’t have to wait for my community to read the story through the perspective of Bilhah and Zilpah for me to do so. That journey started for me in earnest in December 2020, through an independent study project I completed as a yeshiva student in Israel. I spent all of my days in the beit midrash (house of study) learning Torah. I had long been engaged by text study, but my experiences surrounded by a community of folks who were also excited to go deep and wide, over and over again, was like finding my people.

This was an exciting experience I never thought I would have. My parents sought to protect their children from the harmful messages religion and race can carry. This sentiment resulted in them severing relationships with their oppressive traditional religious upbringings. However, I soon discovered that few yeshiva students knew how parts of the Torah have been used to justify the enslavement, dehumanizing, and oppression of Blackness because of the understanding of Cush to be Ethiopia. One example is when Noach curses his grandchildren, the Cush descendants of his son Ham, as עֶ֥בֶד עֲבָדִ֖ים eved avadim (slave of slaves) (Genesis 9:25-26). It is not explicitly clear what Ham did. The Torah mentions Ham seeing his father’s nakedness after Noach, someone with whom God made a covenant to never again erase humanity through flooding, gets drunk and passes out after getting undressed.

This is a story I learned as an adult, filling in the gaps not taught in my rigorous private high school education. When I tried to highlight the historical ramifications of the curse of Ham, anti-Blackness in biblical commentary, and the many Torah references to slaves, I was silenced or ignored by both teachers and students. No one really wanted to look at enslavement outside of our foundational Jewish narrative as slaves who had been saved by the hand of God through Moshe (with support from Aaron and Miriam, who we hear much less about—a further example of the erasure of “supporting characters.”) I was no longer sure where I fit into my love of text study.

When Bilhah and Zilpah found me, I knew they would be with me for a lifetime. As they invite me into study each week, I continue to learn new insights through them, both in Torah and in my life, that I would never have been able to access without them. Choosing to read Bilhah and Zilpah with power and autonomy helps me do that for myself in my own life: still living within a racialized world, yes, but able to find ways to navigate institutionalized systems of racialized oppression with moments of power and autonomy that allow me to make choices—or at least the best choices at my disposal today, to live the best life I can while also trying to seed greater choice for those who come after me.

I started to feel Bilhah and Zilpah with me during my studies. The sense that their voices were directing me evolved into the Bilhah Zilpah Project, a project of Jews of Color Sanctuary, which includes text study, creative midrash, and ritual dreaming through an abolitionist lens. It explores themes, particularly the power of naming, inviting participants to break down and look beyond narrative assumptions through the wisdom of intersection with their own lived experience. We all come to Torah study with so much more than we think we know.

These intersections make it easier to remember that Bilhah and Zilpah had stories before entering the marriage tents of Rachel and Leah. It helps foster curiosity around their relationships and reactions to the people, happenings, and transitions around them. Seeing them as whole characters has led me to hear surprising power and autonomy in their stories. In return, they have helped me connect to more difficult texts and look more closely at contradictions that are sometimes ignored because they feel too hard.

Using the troubled realities of my own life allows a framework to think through opportunities for choice by Bilhah and Zilpah against the backdrop of challenging biblical Near Eastern realities for women. It helps me understand the role they played as parents in a large family on the go. It helps me feel the impact of the intersections and differences in Dinah’s story around sexual violence, reflect on the nuances of how women were given by fathers to husbands, what conditions constitute offering a dowry, and what it means to be taken as a wife. It helps me imagine the intricacies of being in a potentially polyamorous sexual relationship with your sister, two half-sisters, and at least one man. It invites me to transform lack of detail into an invitation to see humanity.

Remembering that Bilhah and Zilpah have voices started out as something I had to remind myself of in the moments when they were not explicitly present. This has become a valued learning tool that adds depth and enriches my reading of Torah. This reminder also mirrors my own modern reality, where amid overwhelming internalized racialized oppression and capitalism, there are small opportunities for choice that can have big impacts as I try to assert balance in my life.

The founding of the United States rests on class separation, dehumanization, and racialized distinctions that institutionalized a system of unpaid labor of convicts, the indigenous, abducted and enslaved Africans, and indentured servants. This uncompensated labor built infrastructure and fed raw materials from southern agriculture to become finished products of northern textile industries. This capitalism is baked into explicit and implicit practices and laws, including our Constitution. It is played out through systems and interdependent disparities that allowed our country to be built by the hands of underclass communities smart enough to run households but nevertheless erased from the narrative. Understanding enslavement in the Torah has taught me a lot about modern slavery. Listening for Bilhah’s and Zilpah’s voices has helped me find my own.

Bilhah and Zilpah enter the story in parashat Vayetzei, which will be read this year on November 25.

The Bilhah-Zilpah Project has officially launched! To learn more, register here.