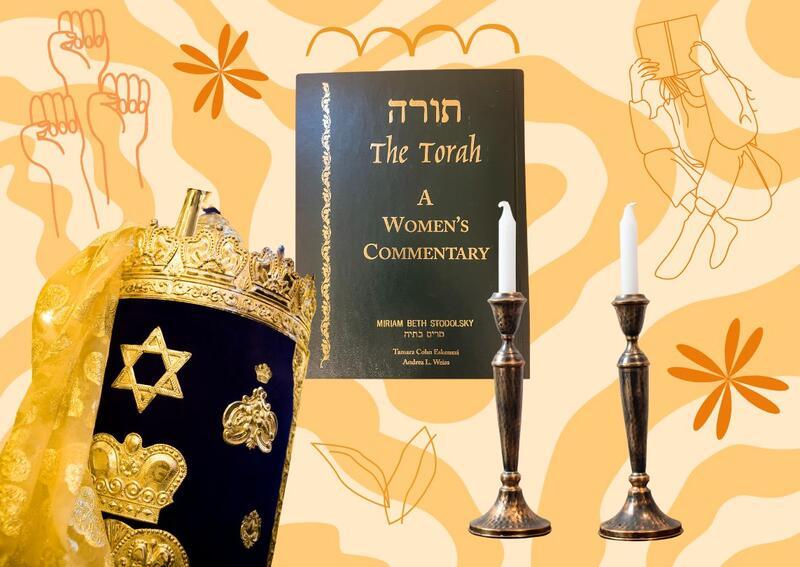

Imagining Feminist Torah Commentary For Everyone

My Reform synagogue gives each b’nei mitzvah a Torah commentary; girls, however, receive a different book of women’s commentary. The book’s foreword describes the core idea of the project: to “help women re-claim Torah by gathering together the scholarship and insights of women across the Jewish spectrum.” For the past year, I’ve been reading the parasha each week from this book. It’s been fascinating, meaningful— and incredibly exasperating. Much of the commentary focuses on trying to interpret problematic passages as actually feminist, even when they explicitly devalue women (not to mention people outside binary conceptions of gender and sexuality). This approach frustrates me, because it seems like an elaborate avoidance of the true issues at hand. Why can’t we face the fact that there are many blatantly patriarchal concepts in Judaism, and still choose to be fiercely Jewish and feminist?

An early example of this evasive technique comes when God tells Eve, “To your man is your desire, and he shall rule over you” (Genesis 3:16). The commentary responds that “God’s words should not be read… as an unqualified mandate for males’ general control over females. In this verse, ‘ruling’ is confined to situations in which desire is at work. The writer may be communicating the power of desire to make one person subservient to another. Another view is that in the ancient context the writer acknowledges a husband’s responsibility for his wife’s sexuality.” To me, this commentary reads as a bid to sweep the troubling nature of “he shall rule over you” under the rug. It provides no evidence to support the foundational claim that “ruling” refers specifically to desire and attempts only to rationalize God’s words. I believe that this rhetoric reveals the true intention of the commentator: not to grapple with patriarchal ideas when they arise, but to shield the text from accusations of sexism.

The commentary’s defensive attitude also incorporates a noticeable element of gender essentialism. One essay on parashat K’doshim reflects, “Holiness seems intrinsically linked in Judaism to separation… [but] do women experience holiness differently?... For those women who form bonded friendships from earliest memory, or who bring the family together, who are the cohesive force in a group, a definition of holiness is needed that does not imply building fences.” Family and friends are not exclusively female experiences, nor do I consider women as a category to “experience holiness differently.” Claiming that women possess an intrinsically unique spirituality does not “help women re-claim Torah;” it only upholds sexist, rigid notions of gender.

This pseudo-feminist mindset exemplifies much of the “Jewish feminism” that my liberal Reform upbringing incorporated: a philosophy which chooses to justify or erase sexist policies, rather than truly wrestling with their significance in order to create a radically feminist Judaism.

For instance, in many households a woman lights the Shabbat candles, while a man recites kiddush. Adults explained this tradition to me as an example of feminism in Judaism, since it makes space for a woman to have an important ritual role, and connects her to other Jewish women. While this is a beautiful idea in some ways, it glosses over so much more: the way that this custom depends on a heterosexual couple, and reinforces the very existence of gender roles. Indeed, this practice usually rests on the argument that a woman, as the housewife, should carry out this symbol of religion in the home. In this light, the “feminist” interpretation represents more of an appealing spin than substantive political discourse.

“Jewish feminism” often prioritizes Judaism in this way, at the cost of ignoring sexism. Alternatively, it gives preference to feminism and abandons Jewishness - such as simply expunging ideas like shomer n’gia (not touching another gender) or tzniut (modesty) from the record, rather than interrogating what they can tell us about actively creating a consent-based culture. This surface-level approach disservices both Judaism and feminism.

In fact, Jewish institutions frequently appear to co-opt feminism, as though it’s just a box to be checked off. Why did only the girls at my synagogue receive a women’s Torah commentary? Shouldn’t we all be Jewish feminists? It’s a well-meaning but ultimately misplaced effort at showing Jewish women that there is a place for them, in lieu of actually going the full mile.

I don’t think that the people who espouse this kind of Jewish feminism bear any malice; on the contrary, they often have the best of intentions. Instead, I blame the belief that Judaism must be defended as inherently correct because any flaw—such as sexism—would compromise its importance. As a Jewish community, we need to move past this perspective. We can even look to our own tradition for many examples of criticizing God or the Torah, from Abraham arguing with God about Sodom and Gomorrah, to the Talmudic principle that “the Torah is not in heaven.”

The women’s commentary made me hungry to seek out a Jewish feminism that doesn’t shy away from confronting patriarchy, nor from engaging passionately in Jewishness. I want to be part of communities where we can discuss topics like Zionism’s impact on Jewish masculinity, the connection between beauty standards and Jewish assimilation, and the Talmud’s understanding of gender. Even more, I want those discussions to have a concrete impact on the world: changing how our Jewish institutions work, contributing to feminist thought, and everything in between.

If I were to give someone a Torah commentary as a b’nei mitzvah gift now, I would want it to be feminist—truly feminist—regardless of the recipient’s gender. It would provide historical context, information on how passages have been understood throughout time, intersectional political analysis, and questions which honor unresolved tensions. Most of all, I would want it to invite readers to ask themselves: what does real, vibrant Jewish feminism mean? And how can I be a part of it?

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.