Q & A with Brazilian Poet Leonor Scliar-Cabral

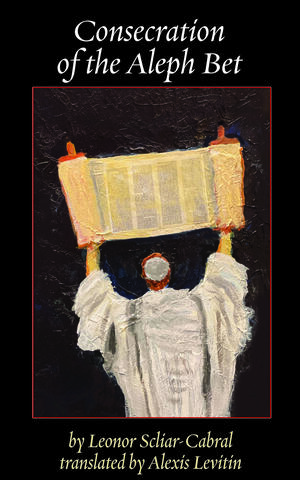

Brazilian poet Leonor Scliar-Cabral is Professor Emerita at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Brazil and a psycholinguist in the field of literacy training. JWA chatted with Scliar-Cabral on the occasion of the launch of her new book, Consecration of the Aleph Bet.

This interview has been translated from Portuguese by the interviewer.

JWA: Tell us about your new book.

Leonor Scliar-Cabral: My new book includes a poem for each of the 22 letters of the aleph bet [Hebrew alphabet]. The poems appear in both Portuguese and English, with translations by my long-term friend and collaborator, Alexis Levitin.

JWA: The book is a celebration of the Hebrew alphabet. What draws you to the aleph bet?

LSC: Since the very first time a book was placed in my hand, I fell in love with books, words, and letters. One of the things that fascinated me about letters is how the part can stand for the whole. In my academic work at the University of Santa Catarina, my work focuses on literacy and how to teach reading.

JWA: What has influenced your journey as a writer and poet?

LSC: The sonnet is an important form in my work, even though the sonnet is not a form that exists in Hebrew poetry or Jewish liturgy. In addition, I was influenced by symbolism, especially the work of Paul Verlain, the poet Lila Ripol and the Brazilian authors Jorge Amado, Graciano Ramos, Cecilia Meirelles, and Monterio Lobato. I did not have much access to Jewish poetry.

JWA: What role has Judaism played in your life and work?

LSC: I am very inspired by Jewish tradition, themes and holidays and have written poems about Shavuot and Tu Bishvat.

JWA: What role has the Jewish community played in your life and work?

LSC: I was one of the founders of the Israelite Association of Santa Catarina, the [Brazilian] state where I live. I even became its president.

The following is a sonnet from Consecration of the Aleph Bet, celebrating the letter hei. (Reprinted with permission.)

Hei

With arms uplifted towards the sky they pray,

exhaling rhythmic cadence with their breath.

Then drawing razor deep they cut away

both head and body, leaving arms bereft.

From the Ineffable their eyes now turn

and left and right all gaze upon their peers,

to find the final self they hope to earn:

and prayer settles in the human sphere.

The vertical turned horizontal now,

three strokes in parallel upon a line

that seal the borrowed record and allow

the voice to speak on Grecian soil: bacchants

who sow their vowels and consonants in time,

contrasted in their endless circle dance.