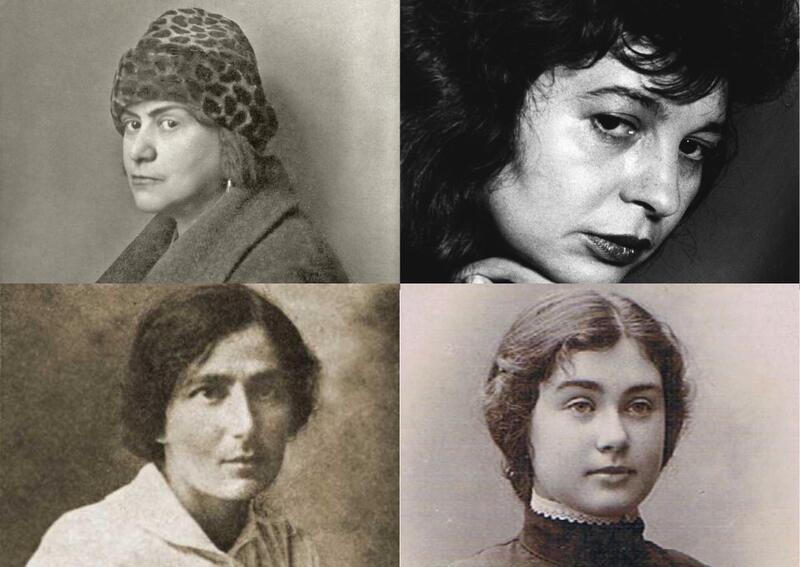

Four Women Who Shaped Jewish Poetry

There are four Jewish women poets from the turn of the last century who tower over their contemporaries, male or female. There is Else Lasker-Schüler and Mascha Kaléko, both from Germany, the one from not long before and the other from not long after World War I. And from Eastern Europe, there is Anna Margolin, who settled in the Lower East Side and wrote in Yiddish, and the Russian Rachel Blaustein, who flourished in Tel Aviv and became the mother of modern Hebrew poetry.

I wanted to learn from them what it could mean to be a Jewish woman, so I translated their books, all of which I was able to see into print by January of 2025. No one listens so closely or hears so deeply as a translator.

Else Lasker-Schüler (1869-1945) came of age in the pre-WWI Berlin of Kaiser Wilhelm—a Berlin that was very much a small town. It was the Greenwich Village of Europe, where hippie-like experiments in communal living and fringe religion were common. Else recited her poetry as a cross-dressing stage persona, Yusuf, Prince of Thebes.

It was a good time to be Jewish. Martin Buber’s books on Jewish mysticism were so popular with German youth that the Buber-fan phase many young people went through was called “Buberty.”

Else expressed her Jewish identity in mystical poetry that owes perhaps more to romantic fantasy about the exotic East than to rabbinic tradition. But she creates magic, and regardless of what she really believed, we believe her. Her poem, A Song of Solomon, is a good example (this translation, as well as those that follow, is mine):

The sweetness of your mouth has taught me

only too well to recognize blessedness.

I already feel the lips of the archangel Gabriel

burn against my breast.At night, clouds hover over my cedars

to drink their root-deep dreams.Your life beckons to me

and I pass away into heartache

as the bud passes away into the flower—

I drift away skywards,

into time, into eternity,my soul glows red

in the sunset over Jerusalem.

Mascha Kaléko (1907-1975) came up hard in a Berlin slum. She was working as a secretary in the Weimar Republic, between the great inflation and the rise of the Nazis, when she first sold her poems to newspapers and became an overnight sensation. Though her poetry never touches on explicitly religious themes, it has the archetypal Jewish qualities of moral warmth, humor, and deep belief in the value of life in this world. She writes about the love and loneliness, hard times and budget holidays, with such impish wit, everything she describes seems a merry adventure. Here's the poem that opens her book, The Secretary’s Helicon, "I Interview Me":

“I was born, not terribly long ago,

in a little town where anyone’s private business

would soon be matter broadcast

for everyone’s entertainment.

It had one church,

two or three physicians,

and a very large home for the mentally ill.“When I was a child, my favorite word was ‘no,’

I was no poster-girl for the joys of motherhood—

in fact, when I think back, I don’t suppose

even I would have much enjoyed being my mom.“I entered eighth grade in public school

during the First World War;

when I turned twelve, I still believed

when the fighting was over, there’d be peace.“Two of the senior teachers thought me gifted,

so much so,

they made sure I was sent

somewhere far from them, where I could get

the kind of education I deserved.

So I found myself at a better school,

whose excellent curriculum, nonetheless,

failed to teach me what ‘downsizing’ was.“At graduation, a teacher made a speech

about the hazards to which youth

is all too often exposed,

and the importance of ethical standards,

and he told us

we were now entering life—

which somehow ended up meaning an office.“Eight hours a day I carry out my tasks,

do my underpaid duty,

at night I find the time to write poems,

which, my father observes, ‘will really help.’“When the weather is nice, I give myself to travel—

that is, I run my finger over a globe;

and on rainy days, when there’s nothing to do,

I wait for happiness to find me.”

Mascha fled to America when the Nazis came to power and continued to write but never recaptured the sparkle of her first book. She was a briefly dazzling facet of Weimar in its final days.

Rosa Lebensboim, known as Anna Margolin in 1903. Critics claim she authored the finest Yiddish poetry of the early twentieth century.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Anna Margolin (1887-1952) lived in the New York City of jazz clubs, bootleggers and gangsters—which was also a New York City with a huge Yiddish-speaking community that supported a galaxy of Yiddish theaters and newspapers. Thus, in a sense, Anna never left her native Jewish Russia—where she lived in dreams about Paris! Hers was the Fin-de-Siècle poetic world of the Decadents and Symbolists, Baudelaire and Rilke. If Poe had had a Yiddish sister, it would have been her. Here's her poem, "My People Speak”:

The gallery of my forebears, my people:

men in velvet and silk,

long pale faces,

lips that indicate a weary sensuality,

delicate hands that rest caressingly

on grand old folios—

late in the night they talk to God.Merchants from Leipzig, Danzig,

their fine white cuffs, the smell of expensive cigars,

the scholarly wit of men

who’ve grown up pondering the Talmud.

With fine manners, speaking perfect German,

they’ve the dull sly eyes of businessmen,

cunning, successful, sated.

Don Juans, salesmen, mystics,a drunk, a pair of apostates in Kiev

submissively kissing the cross.My people:

women set with gems like pagan idols,

diamonds starry against the red night

of Turkish shawls,

in heavy lustrous folds of French satin

their bodies are lithe, svelte

as a weeping willow’s long hanging branches;

hands in their laps like an arrangement

of dried flowers. Extinguished desire,

drab and overshadowed in their lovely dead eyes.Grandes dames in calico and linen,

big-boned, strong, athletic,

with easy, scornful laughter,

calm speech and eerie silences.

I see them at night, through the windows of my cottage

unexpectedly erected, like statues.

In the twilight of their eyes flickers

cruel delight.And then, there are a few,

I say it with shame, who sold themselves

for a few rubles.They’re all my people, blood of my blood,

the flame from which my own was kindled,

all of them mine, living and dead,

sad, grotesque, and noble,

stampeding through me

as through a lightless,

a haunted house,

banging and praying and cursing and weeping,

making my heart thud

like a great knelling bell of flesh,

my mouth falls open,

my tongue flutters,

the voice isn’t mine—

my people speak.

Rachel Blaustein (1890-1931)—her name is usually spelled “Rahel” out of an unhelpful deference to Hebrew orthography—was the hero of my literary pilgrimage. A Zionist of the Second Aliyah, she created a new poetic idiom out of spoken street Hebrew—her contemporaries were still writing in the “King James Hebrew” they’d learned in the cheder. Though not traditionally religious, her love of the land and her sense of this all-redeeming moment in Jewish history suffuse her work with mystical force. It would be fair to say that Rahel didn’t practice Judaism; she perfected it. She shows us in her poetry, as in her poem "Rachel," a transfigured world, deepened with meaning, where even accidents revealed a pattern in the fabric of her days:

The voice you recognize in my songs

is hers, as surely as the blood in my veins

flowed in hers, my far fore-mother,

it flowed in hers, the same.Any house seems small,

all indoors has the feel of a trap.

I’m never at ease in a city,

never understood the appeal of an address.What can I say, except that I came

from that same Rachel whose scarf fluttered free

as a nomad’s banner in desert wind?I always know where I’m going,

don’t need sign or map or even street

to keep to the path that’s mine alone.

My legs remember, my feet repeat:

Rachel!

—as she went then, so now I go.

The poetry of these four magnificent women amply repaid all my efforts in learning their languages. They were women who defied convention to write at all, and found their own idiom, which owed nothing to the style of their male predecessors. The battle they fought for women’s voices to be heard is still being waged, as their continued exclusion from illustrious anthologies attests. And they all suffered from antisemitism, which forced them out of the lands they were born in.

All of these women have enriched me. I cannot imagine my life without Mascha’s winsome wit, Else’s psychedelic enthusiasm, Anna’s goth glamor, and Rachel’s beautiful pride.

Thank you. As a Jewish poet myself, I know

the work of Else Lasker Schuler but am grateful to meet that of the other women.