Painting Courage and Painting History

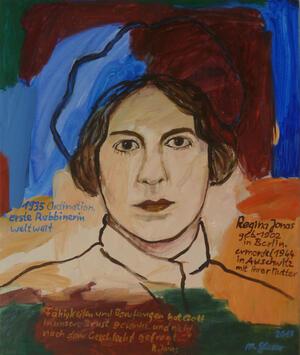

Marlis Glaser, a German artist, grew up in rural Germany, not knowing any Jews or her father’s previous involvement with the Nazi party. After painting the portraits of social democrats, union members, and communists in 1984, Glaser was introduced to a German Jewish woman who had survived the Holocaust. Now, 33 years later, Glaser has shaped her art around Judaism, and recently converted. Her colorful work includes hundreds of portraits of Holocaust survivors, their families, and other Jewish figures throughout history. She has also painted a portrait of the first ordained female rabbi, Regina Jonas, who was killed in Auschwitz in 1944. Three years ago, Glaser won the Obermayer Award, which is presented to German non-Jews who have helped preserve the history of German-Jewish communities. Glaser’s art has been shown in galleries throughout Europe and Israel.

I had the opportunity to speak with Ms. Glaser about her incredible art and mission:

What inspired you to paint a portrait of the first female rabbi, Regina Jonas?

First, it was the excitement that the first female rabbi is part of German-Jewish history. Second, I chose to paint a portrait of Regina Jonas because she wasn’t well known to visitors of my exhibitions. I wanted to remind them that there was a well-educated, academic woman who was a victim of German persecution.

As a Jewish woman, what was that experience like for you?

My first portrait painting of Regina Jonas in 2014 was more detached and focused less on her courageous character—see the cool blue colour and her polite smile. I painted this portrait for my event with an exhibition for the European Day of Jewish Culture with the theme of “Women in Judaism.” For my last exhibition, “Gesicht zeigen” (Show Face) in 2017, the focus was on Jewish women who had shown courage, humanity and dignity. So I read Jonas’ story again and was deeply impressed with how much strength and courage she must have had.

At this point, I felt closer to her and so I painted her with more power and passion, and intentness in her facial expression. I chose warm colors this time to illustrate her behavior in the concentration camp, where she provided comfort to others by as a community and spiritual leader. I used a warm blue color as a symbol for longing and fantasy to represent her hope that there might be peace in the future. This warm blue is a blackberry shade with a tint of red. I mixed in the red, symbolizing Jonas’ strength as the first female rabbi. I felt pain for her. I am only able to finish my portraits after I have felt empathy for the subject of my painting.

What do you believe is the importance in portraying the faces of those who have been lost and who have survived the Holocaust and their children, especially to a European audience?

By illustrating their faces and names and individual stories, I wanted to show that we miss each victim. They should be here today as they were hundreds of years ago, with their work, ideas, families, innovation, and creativity. What a huge loss for both the Jewish people and Europe. It is sobering to think of the criminal heritage of many German citizens today.

What has the response to your paintings been from survivors and their families? What about non-Jews?

The survivors were astonished about my interest in Judaism and that I had already created art related to Jewish traditions and festivals of Jewish festivals before I converted. When I started to work with most of my subjects, I would bring my catalogue book from 2004 with pictures of my paintings inspired by the poems of Else Lasker-Schueler and the holidays of Shavuot, Sukkot, Rosh Hashanah. This action was helpful in getting them to trust me.

When the exhibition of portraits, symbols of names and trees was shown in Nahariyah in Northern Israel, many visitors were the children and grandchildren of survivors and immigrants; some of them thanked me personally. I once received a letter from a non-Jew which asked: Why do you only draw Jews? I was upset, and wrote back: Why not?

The truth was that, throughout my years of pursuing art, I have always painted Jews because of my focus on the labour movement, communists and social democrats, and influential women from the growing feminism movement. Jews have always been key players in these movements.

Are there any Jewish artists whose work you find particularly arresting or inspiring?

Arresting? Yes, William Kentridge, a South African artist who makes animated films, prints, sculptures that often portray the reality of apartheid and totalitarianism. Inspiring? Shmuel Shapiro. He is a wizard with colors. He influenced my work about the love poems of Else Lasker-Schueler.

In general, what has your experience been as a converted Jew living in 2017 Germany? How does that connect to your art?

My art didn’t change – Jewish history and presence, Jewish people and traditions have long been the subject of my art. But my feeling towards it has changed, it’s now become natural for me to see these themes in the centre of my art. And it’s a relief to know where I belong. I’ve been told that my paintings have become more energetic since – I can’t really see the difference, I’m too close to them, but I certainly feel stronger.

How do you decide on different colors, shapes, and symbols to include in your paintings?

Well, first I have to educate myself about the personality of the subject. I collect and read books and letters, and, if the models are alive and in front of me, I ask them questions and follow their gestures and voices. This is the fundamental base for my decisions about intensity of colors, shades, quantity of color areas and contrast. For the portrait I painted of another woman rabbi, Elisa Klapheck, who actually wrote the biography of Regina Jonas, I started by watching her give a lecture. She was very clear in her sentences and intellectual in her thoughts. So, for her portrait, I chose cooler, brighter blues and greens.

For my portrait of the French politician Simone Veil, I honed in on her elegance and stylishness. I painted her with a splendid jacket with a pattern on it similar to the pattern in the background of the painting. In the background I wrote a quote from a 1795 ketubah in order to represent Veil’s Jewish identity. Through these patterns, quotes, and structural choices, I hoped to illustrate Veil’s powerful personality, influence, and legacy.

Your other paintings include series on twentieth-century feminism, women in the French Revolution, and women in World War II. What is the importance of painting women from historical movements, and including their stories in the narrative?

We are all part of society, but we cannot understand ourselves without knowing our history. And learning about powerful women of the past can provide us with the comfort and strength to effect change in our own lifetimes. A portrait, a painting, or a drawing alone cannot give us much information about the political and the individual context of a human being and time period. Because of this, all my portraits have words and sentences beside the head, often historical information, inscriptions, or quotations.