Of Peonies & Penises: Anita Steckel’s Legacy

Anita Steckel was 82 when she died last March. But Anita, her many fans would insist, was way younger than most of us will ever be.

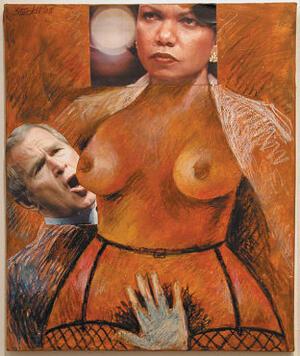

When you read about Steckel’s artwork, it doesn’t take long for the words “erotic” and “feminist” to surface. Yes, Anita did regularly pay visual homage to overtly sexual male and female nudes. And yes she did create a series honoring the male organ in visibly excited states. And yes, in defending that series, she did famously say (according to The New York Times no less), “If the erect penis is not wholesome enough to go into museums, it should not be considered wholesome enough to go into women.”

Let’s face it, even today this packs a punch. But it was considerably more shocking in the art world of the early ‘70s, an era when a woman was still expected to paint (if she painted at all) not penises but peonies.

The backlash to her brazen celebration of sexuality––male and female alike––prompted Anita to band together with a number of other female artists to form the Fight Censorship Group.

Indeed ladylike refined sensibilities were anathema to Anita. “Good taste is the enemy of art,” she told the audience at a 2007 panel discussion at the University of Pennsylvania. “It’s wonderful for curtains, but in art it’s suffocating.”

And taking another potshot, this time at patriarchy and pop art, in 1963, Anita named a series of her work “mom art.”

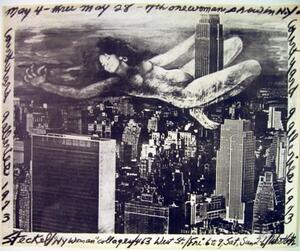

But Anita wasn’t all talk. She painted the world she saw, injustice and all. And her vision was on the grandest of scales, as often as not with tongue firmly planted in cheek. In one of her most famous series, spotlighted in a 1976 feminist exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, a memorable image finds Anita’s nude self-portrait flying over the Atlantic Ocean, through Europe to the Vatican. We are not a bit surprised when she winds up on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, joining Michelangelo's fresco of the Creation of Adam.

One ardent Anita Steckel fan is Richard Meyer, an art historian at the University of Southern California, who praises her not only for pioneering in the space where art and social activism intersect, but also for her audacious use of mixed media. Anita’s CV boasts a list of exhibitions that sprawls over three full pages, many of the shows worlds away from her cozy Greenwich Village studio.

“Anita Steckel was a visionary artist whose work addressed issues of gender, pleasure and sexual politics well before the founding of the women’s art movement,” is how Meyer puts it. “She was fearless.”

Anita also inspired generations of young artists through her 28 years of teaching at New York’s Art Students League. One of them, Jessica Maffia, is curating an exhibit of Anita’s last series to run July 14-29 at the Westbeth Gallery at 55 Bethune St. in New York. “Anita was a fiercely supportive teacher who taught drawing skills in an atmosphere of love and kindness,” Maffia told us. “Her belief in me enabled me to restructure my life in pursuit of art … I miss her terribly.”

You can read her obituary in the New York Times.

For thousands of years men have turned to the female form for inspiration. Why has it taken this long for a woman to do the same? Do you find her work erotic? Inspiring? Off-putting?

This post is the fourth in a series on “Jewesses with Attitude”—Women Who Have Inspired Change.