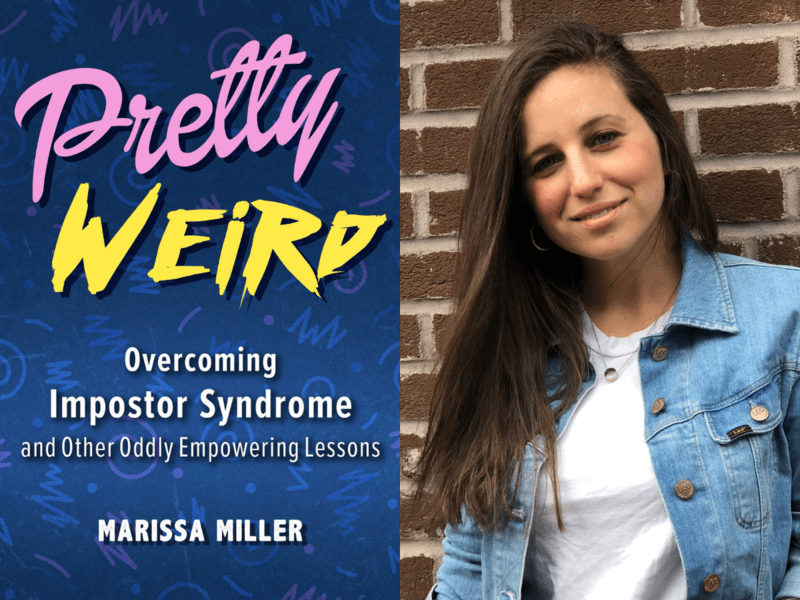

Marissa Miller Says Being Weird Is Good

JWA sat down with writer Marissa Miller to discuss her essay collection Pretty Weird: Overcoming Impostor Syndrome and Other Oddly Empowering Lessons, published in May 2021. Miller’s debut book highlights the awkwardness of growing up, the difficulty of managing a freelance writing career, the importance of Jewish culture, and the struggle of living with disordered eating. From depicting a living situation gone wrong to experimentation with sexuality at Jewish summer camp, the book is full of personal anecdotes that showcase her intersecting identities. Even if you aren’t a writer, you may relate to some of Miller’s “pretty weird” experiences.

Growing up, you pushed the boundaries of what being a good Jewish girl looks like. What do you hope that other Jews who may be constrained by societal pressures take away from your book?

If you ever feel neglected by or alienated from a certain group of people, they aren’t your people anyways. You shouldn’t have to feel pressured to fit into a certain mold, and I imagine anyone who cares about you would agree, whether you’re renegotiating your religious identity, or exploring your sexuality, or toying with the idea of pursuing an alternative career path. Find a way to practice Judaism in a way that makes sense to you and feels fulfilling in your own way. What good is reading a prayer you don’t understand if you’ve found other ways to speak to God, or your version of Them? The few times in my life I’ve felt any connection to the nebulous concept of God, I’ve probably been writing or dancing. That doesn’t make me a “worse” Jew than someone who observes in a traditional way.

In a lot of Jewish families, I feel like there is pressure to be perfect. How did this perfectionism play into your eating disorder, which you write about in your book?

Perfectionism doesn’t just play into my eating disorder, it is my eating disorder. I used to think I had this pathological compulsion to be thin, and it stopped there. But it’s so much deeper than that. In many Jewish families, there’s an unwillingness to acknowledge anything is wrong with our mental health, because God forbid the family next door suspects any household dysfunction. Do you know how afraid I was to tell my parents something was wrong? They hadn’t dealt with these types of issues before, at least not out loud, so I had this fear they’d think it was a reflection of their parenting. I’ve heard of kids in Jewish families who go untreated for years because major depressive disorders were mistaken for standard sadness, generalized anxiety was interpreted as Jewish neuroticism, and eating disorders were seen as cries for attention. There’s also so little understanding of what an actual eating disorder patient looks or behaves like. I found myself almost having to perform my mental health issues before anyone took them seriously. I had told friends and family really, really dark stuff about what was going on in my head because I didn’t think the intake worker or receptionist at the mental healthcare facility would take someone as seemingly high-functioning as I am seriously. I needed the validation from someone else that I was sick enough, that I was the perfect patient worthy of help.

In your book, you wrote about your relationship with your bubby [Editor’s note: The author prefers this spelling.]. Has she read your memoir, and what was her reaction?

My mom initially didn’t want my bubby reading it because of all the sex stuff in it, but she was like, “It’s okay! I can handle it!” She ended up zooming through the book in a couple days, and all she came back with in broken English was “It was nice.” Intergenerational trauma plays a huge role in my eating disorder, beginning with her story and attitudes toward food post-war, but she doesn't really understand the concept of mental illness and didn’t draw that link. I've tried to explain to her what anxiety means, and it hasn't clicked. It's a really wholesome thing to see, actually, because talking to her helps me realize not everything has to be so complicated it hurts.

And I’m still honored that she read it and that she insisted I sign her copy.

Montréal is a very Catholic city. Did you ever feel “pretty weird” being Jewish growing up and still living there?

I don’t think I’ve ever gotten the true, secular Montreal experience because I went to private Jewish school for thirteen years. I almost think being immersed in a hyper-Jewish environment made me feel weirder than I would have if I were around kids from different backgrounds because my peers had this narrow vision of what everyone in the community should be, and I was definitely… not that.

Telling your parents that you wanted to be a writer went pretty well. What advice would you give to other teens (or maybe older people) who are nervous about telling their parents what they really want to be when they grow up?

You just have to go for it. Rip the Band-Aid off. No parent wants to see their child live a life they thought was expected of them only to see them suffer as a result. Be your realest, truest self, and all that good stuff your parents wished for you will follow naturally. And if they still don’t accept you, you are well within your right to set boundaries and seek support from a chosen family, be it old friends who know you better than anyone else or folks in your field who get it.

Dealing with imposter syndrome, which I can definitely relate to as a freelance writer, is an important part of your book. What has your relationship with imposter syndrome been like during the pandemic?

It’s so funny to have written a book about impostor syndrome and then get impostor syndrome about that very accomplishment. I can’t say for sure whether the pandemic has exacerbated it in any way, but I do know the last year or so tested my resilience and confidence. It’s only through challenges like these that we get to look at ourselves and be like, “Damn, look at what I just got through. There’s so little that scares me now because I’ve seen it all.”

What advice do you wish someone told you about entering the media industry?

If you’re constantly told you’re unable to do something, you’re way less likely to pursue it. I wish someone told me that it’s possible, that we’re not all doomed to fail. And I wish I was told, just once, that if you work hard enough at freelance writing, you’ll be able to get by comfortably and even write something you’re proud of along the way. There’s so much rhetoric about how impossible that is, so going into my own career with such a small idea about what my professional future could look like was super disorienting because I now have this book deal with a big publisher, I’m represented by a fantastic literary agency, and lots of people seem to enjoy my work, and it’s like, what? This was not part of the plan. But hey, I’ll take it. And if I can help at least one of my readers acclimate to their new success through my book, my work here is done. Or maybe it’s just begun.