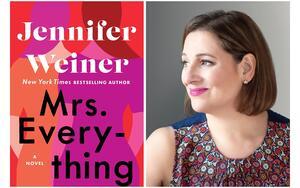

An Interview with Jennifer Weiner, Author of "Mrs. Everything"

JWA sat down with author Jennifer Weiner to discuss Mrs. Everything, one of JWA’s 2019-2020 Book Club picks. Weiner's latest book chronicles the lives of two sisters, Jo and Bethie, following them through the decades from youth to adulthood. The novel tackles issues from body image to Jewish culture to reproductive freedom to civil rights. Weiner's next novel Big Summer comes out on May 19 and also deals with themes of body positivity, female friendship, and living out loud and online as honestly as possible.

As a University of Michigan alumna and a Northeast native, I felt at home in the two settings that you chose for the novel: Detroit and Boston. Why did you choose these places? Do you also have a personal connection to these cities?

I do! My extended family on both sides comes from the Detroit area. Then my parents moved to Connecticut, so that’s where I grew up.

In the beginning of the novel, there is a brilliant scene featuring a theatrical production of the Purim story. The girl playing Vashti rebels by actually acquiescing to King Achashverosh’s request ironically, so that she may continue to have a voice and presence on the stage. How did you conceive of this scene, and was any of it based on true events? It was epic.

I’m glad you liked it—I had a blast writing it. One of the books that inspired Mrs. Everything was Rita Mae Brown’s coming-of-age novel Rubyfruit Jungle. That book features a heroine who knows she’s different, and finds her voice when she’s cast as Mary in the Christmas pageant (different holidays, same dynamics, including an onstage shoving match). I have never disrupted a Purim spiel, but having participated in and watched many of them, I had a great time imagining the chaos that could ensue if a kid decided to, shall we say, resist direction.

In Mrs. Everything, you introduce a character named Jo. As I got to know her, I couldn’t help but think of Jo in Little Women—both challenge the gendered expectations of their time, and both dream of being writers. Is your Jo an homage to Louisa May Alcott’s Jo?

Yes! Both Jo and Bethie are modern-day reimaginings of two of Louisa May Alcott’s March sisters. I wanted to show how the world has changed, and how it hasn’t, in terms of the lives and the choices that women are allowed. So, my Jo lives in a world where she’s “allowed” to be a writer—but not live with the woman she loves. And my Bethie doesn’t die as a young teenager—she survives and endures some of the pitfalls that even “good girls” can encounter.

In the novel, you mention books like Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Shere Hite’s Sexual Honesty: By Women for Women, and Ira Levine’s The Stepford Wives, among others. How and when did you discover these works, and what impact did they, or other such books, have on your own growth and development as a woman, a writer, and a feminist?

I grew up in a feminist household with a mother who was a reader, so most of those books were on her shelf. I read them casually when I was a teenager, and then, after I went to college, more rigorously in my women’s studies, politics, and sociology classes. Everything I learned in those books played a part in who I became, but probably The Stepford Wives most of all, because that book showed me the power of fiction. You can have every fact at your fingertips, you can recite every statistic in the world, but if you can tell a story, or a parable, about oppression and inequality, it’s going to be far more memorable.

Like the Women’s Health Collective (who ended up writing and publishing Our Bodies Ourselves), the fictional women who run the consciousness-raising collective in Mrs. Everything are Jewish. However, they do not discuss or address their Jewishness openly or explore how being Jewish brought them to their work. Can you talk a little bit about how you made the decision to make these characters Jewish and why they don’t address their religious background head on?

Maybe I’m wrong, but I think that, for women of my mother’s generation, questions of religious identity didn’t feel as pressing as questions about gender. Some of the women in the consciousness-raising group in Mrs. Everything are Jewish, and some are not, but what they have in common is that they’re all women, all wives and mothers, all living a version of a life that the majority of women at that time chose. (But who knows? If we saw them again, maybe they would be talking about religion!)

The novel alternates between the perspectives of several characters and spans time periods: from 1950 to 2022. Which era did you enjoy writing the most, and during which era do you think there was the most hope for women’s equality?

I have to say that the 1950s and 1960s were a lot of fun, because of the music and the fashion, but also because I found things in those years that surprised me. I went back and read issues of women’s magazines of that era, and I expected that there would be a lot of diet tips and beauty tips and how-to-get-a-man advice. What I found instead were stories about signing up to be an exchange student, or a profile about a teenage girl who moved to New York City on her own to try to make it on Broadway. There were stories about how to be a hostess, and there were diets, but even those were refreshingly reasonable (Step one was always “check with your doctor and make sure you actually need to lose weight,” and step two was “don’t do anything radical or unhealthy.” I’d been expecting cabbage soup fasts!)

So I loved writing about that era. Meanwhile, the present-day scenes ended up being the most depressing because I was writing just as the #MeToo movement was at a point where it felt like every day I’d wake up and find out that some other prominent man had been exposed. It made me wonder what it’s going to take to create permanent change, and if that’s even possible.

At JWA, we often say that telling and listening to people’s stories is transformational for both the storyteller and the listener. As a fiction writer, you bravely draw from your own personal narratives and struggles. Have you received feedback from readers about the impact that sharing bits of yourself has had on their own struggles or healing processes?

Stories are so powerful because they give us a chance to see a version of our own truth, and to know that we aren’t alone in our experiences, whatever they may be. When I blogged as a new mother, writing about how hard and how endlessly boring life with a newborn could be, I remember hearing from women who were grateful that I was talking about it, and grateful that we lived in a world where we could talk about it openly and not feel ashamed. With Mrs. Everything, Bethie’s story, unfortunately, seemed to resonate with a lot of readers—the way that sexual abuse can alienate a woman from her own body; the way that food goes from nourishment to a way to shove down the pain. I heard from readers who saw themselves in Bethie… and from readers who had the experience of a parent coming out late in life.

There’s a Muriel Ruykeyser quote that I think about all the time: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.” I believe that! I believe in radical truth-telling because I also believe in tikkun olam and in doing the work of repair. Once the world has split open, we can rebuild it and make it stronger.

Many women have many different selves, identities, and careers over the course of their lives and they evolve, adapt and grow. In Mrs. Everything, which character’s evolution was the most interesting for you to write?

I think the most interesting arc was the switch between Jo and Bethie—the “good girl” ends up submerged in the counterculture, while the rebel ends up married in the suburbs. I wanted to show how radically a woman’s path can change over the course of a lifetime, how each of us contains multitudes, and how it’s never too late to make a change.