Jessica Kirzane on "Diary of a Lonely Girl"

A few years ago, while I was researching a footnote for my dissertation at Columbia University, I typed the words “fraye libe” (free love) into the search box on the Yiddish Book Center’s website. The first result was a novel I had never heard of called Tagebukh fun an elender meydl oder der kamf gegn fraye libe, or Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle against Free Love. That’s how I met one of my best friends.

There are many metaphors that translators use to describe their process and their relationship to the original author. Some translators think of themselves as “conduits” or “reproductive printmakers,” or they see themselves as pouring precious liquid from one vessel into another. The metaphor of the translator as a midwife enabling the birth of the translated text in its new form is widespread and evocative. In 1603, John Florio discussed his translation of Montaigne’s Essays as though the text were the author’s child who had been adopted and raised by the translator who served as its foster father. For me, translating Diary of a Lonely Girl has been like developing a friendship with Miriam Karpilove.

Reading Karpilove’s work, discovering the ways that she made me laugh, wrapping my language around hers, I felt I was getting to know someone intimately and deeply. I could anticipate her syntax—we finished each other’s sentences.

Miriam Karpilove’s life is entirely different from mine in almost every way. She preceded me by a century, and her identity and experiences were bound up with her life as an unmarried woman without children while I eagerly told my husband about her writing and translated her work largely during my kids’ naptime and after they were in bed. Yet, the more I got to know her, the more I felt we had in common. We were both writers, hoping that our work would reach and move people. We both experienced a kind of precarity because of our careers—hers because her stints as a staff writer for various newspapers were interrupted by periods of unemployment, and she often felt that she couldn't break into the inner circle of Yiddish publishing, and mine because for much of the time I was working on this translation I was teaching as a part-time adjunct, a notoriously unstable form of academic employment. Most of all, we were women skeptical of, and angry about, living in a world in which women’s perspectives, labor, and bodies are so often controlled and undervalued by men.

So there was a real pleasure, for me, in bringing Karpilove’s work into English. It was a chance to express something Karpilove and I were both feeling, and the more I felt I understood her text and was aptly interpreting it, the more understood she made me feel too.

Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle against Free Love was serialized in the newspaper Di varhayt in 1916–1918 and published in book form in 1918. It is a first person account of a single Jewish woman living in New York at the turn of the century and the pressures she experiences in her dating life. The narrator engages in a series of romances with freethinking young men who are eager to pursue free love—affairs without marriage—claiming that such relationships are in line with a political standpoint that rejects patriarchal authority. But they don’t see, or care, that such affairs are dangerous for women who have to protect their respectability in order to maintain their social standing, or even simply to have a place to live. Along the way, the narrator pines after a man she loves, makes fun of a man she hates, and defends what she sees as women’s dignity. You might not know it based on this description, but Diary of a Lonely Girl is also a very funny book. It is packed with sharp, quick dialogue full of barbs and comebacks, sarcasm and wit.

Diary of a Lonely Girl is also quite political. It describes love as a battlefield, when in the wake of World War I, war was a particularly fresh and raw topic. Although the novel rarely directly mentions the war, Karpilove fills her discussions of love with metaphors of war, insisting on the urgency and relevance of women’s disempowerment in sexual relationships even in a time when men are dying by the thousands. By using militaristic language, Karpilove insists that issues of women’s dignity are not secondary or frivolous, but should be central to political and social reform.

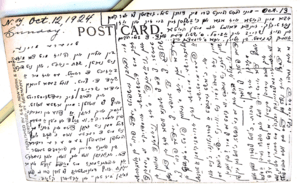

Since I completed the translation, I have continued to research Karpilove and her writing. Just today, I read a postcard to her brother Jacob Karpilove dated October 12, 1924. In it, Karpilove writes, “Today I registered to vote: my first vote. I’ll have a say in the government of America, since I’m a citizen, after all. No one should say that I shouldn’t exercise my right to help elect a better government.” Several years earlier, in 1918, Karpilove published a piece in the Yiddish newspaper Di varhayt describing her observations of women voting in the first election in New York City in which women were legally permitted to vote, when citizens of several districts voted to fill vacancies left by Congressional representatives who had resigned. In this piece, she details how women were harassed in the polling place and made to feel shame for their actions.

Nevertheless, despite her direct experience with the mockery women voters faced from men at the voting booths, including poll workers and policemen, in 1924 Karpilove registered to vote in the second presidential election in US history for which women had the right to vote.

When I read Karpilove’s postcard to her brother, I was not at all surprised to learn that she had decided to vote. Karpilove was a woman who, at least in her writing, prided herself on being modern, brazen, independent, and unapologetically assertive. What I was surprised by was that she gave the event of registering to vote so little space in the postcard, in which she also complains that she has wasted too much of her time on romance when she could have been reading and writing, and describes several plays she had been to see at the Yiddish theater. But the more I read the postcard, the more I felt that the very lack of space that she gives to this moment speaks volumes. These few sentences about voting, so matter-of-fact and certain, seem to insist by the way they are buried within the postcard on Karpilove’s belief that women’s civic and public participation should not be taken as surprising, but should be part of women’s everyday lives. Why dwell on it? Of course a woman should vote, and what else is there to say?

I have been reading and researching Miriam Karpilove for several years now, and I keep stumbling upon these hidden gems: moments of stubbornness in which Karpilove insists on women’s equality and worth, almost as a matter of course.

I hope that those who read my translation of her Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle against Free Love will find it empowering to get to know Miriam Karpilove and discover her confident, no-nonsense voice. And I hope you’ll find her to be a friend, too.

Diary of a Lonely Girl is one of JWA’s 2019-2020 Book Club picks.

Hi Dr. Kirzane, This so cool!

You've certainly peaked my interest. Thanks for sharing your experience.