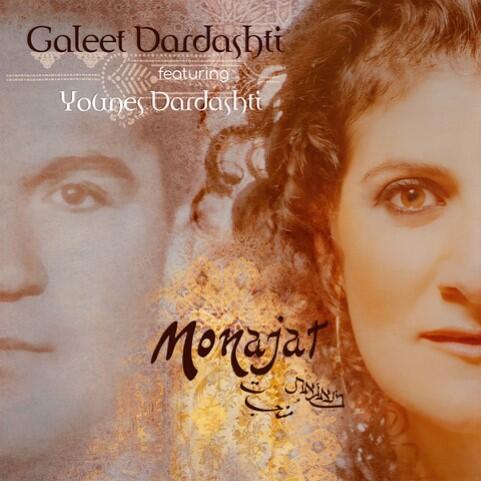

7 Questions For Galeet Dardashti

JWA talks to Dr. Galeet Dardashti, cultural anthropologist and singer, about her new album Monajat.

JWA: Can you speak about the title of the album? For our readers, monajat can refer to an intimate conversation between yourself and another person, or an intimate conversation or prayer between you and God.

Galeet Dardashti: The inspiration for this album came because I fell in love with this recording that my grandfather made in Iran of some of the prayers of Selichot [prayers of repentance]. My grandfather was one of the most famous singers of Persian classical music in Iran. Being a cantor [in Iran] is not a profession; it is a volunteer venture that you do. He was a famous singer, so it would be so exciting for the community for my grandfather to lead prayer for them —all these different communities in Iran.

Now the Selichot service is done in Sephardi-Mizrahi services for the entire month of Elul before Rosh Hashanah and in between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Every night, in the Persian tradition, Selihot starts at 4 am and goes until shaharit [morning prayers]. My grandfather was often asked to lead the Selichot prayers and he would do it at different people’s houses, often outside. He would lead services in the courtyard and people would hear him in the street. A lot of memories of my grandfather leading services —people have memories of that. These recordings that he made of him singing these prayers, he ends all of the prayers with this rendition of a piece called Monajat. I had it translated because my Persian isn’t amazing, and it's a poem very much in the style of a Rumi poem and so I thought it was a Rumi poem. When I sent it to experts, no one could find it, and we think my grandfather wrote this poem in the style of Rumi. And it makes sense, because my grandfather, as a professional singer of classical Persian music, he would chant Hafez and Rumi and interpret them. These prayers are written mostly by Sufis [Islamic monist mystics] and they were about prayer and about worshiping the divine. It’s powerful, beautiful and it’s in Persian.

This was my grandfather’s innovation, his innovation of the Selichot ritual, and it was powerful because it was an expression of his Persianness and his Jewishness as one. It was totally natural for him to chant this Persian poem that he wrote at the end of Selichot services and it’s also a perfect example of how my grandfather as an artist was innovating Jewish ritual. That really gave me artistic license to be able to do it myself and to take these prayers and create something artistic with them, because my grandfather was already doing it in Iran. That's why I called the album Monajat. It was the best way to exemplify this shared culture and the way my grandfather was doing that in Iran.

JWA: What was your relationship with your grandfather like growing up?

GD: I didn’t know him that well, because we didn’t have a shared language. He didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Persian at all. He passed away when I was 20. I barely had an opportunity to have a meaningful conversation with him, let alone sing with him. I had a closer relationship with my safta [grandmother]. I would see him maybe once a year, but we didn’t have a way of connecting deeply. I was amazed because we would go to Persian events [in Israel] and people in the Persian community would go ‘Younes, Younes, sing for us!’ It wasn’t music I grew up with and so it sounded foreign and beautiful to me. So I didn’t have a way of connecting with him. And so really, after having studied Persian music and having gotten more deep into it, it’s been exciting and moving to reconnect with him in that way…to sample his voice, to sing with him in unison, to duet. It’s been intimate.

JWA: How has the album been received by Persian Jews, including your family?

GD: I mean, look, it’s still pretty new, and I’m still getting feedback from the Persian Jewish community, but so far it’s been very positive. I haven’t had enough direct feedback from the Persian community in large enough numbers to tell you yet, but my family is really excited about it, and I hope to share it more and more with the Persian Jewish community.

JWA: Concerns about ‘qol ishah’ [the permissibility of hearing a woman’s voice] seem to always come up when discussing Jewish women singers. But when I think of Jewish women, I think of great singers and thinkers: Roza Eskinazi, Salima Pasha, Leila Murad, and even Paula Abdul. What are the historical and current attitudes to women’s performance in your communities? How have they affected your process with Monajat, if at all?

GD: I would say it hasn’t affected me much. I am only invited into certain spaces. But of course, I don’t feel limited, because I'm very welcome in the spaces that I'm invited to exist in. They wouldn’t be inviting me if they weren’t excited about what I was doing. I guess it’s that I don’t attempt to enter spaces where I’m not welcome and where my singing as a woman chanting sacred music would not be accepted. It’s self-selecting. I wouldn’t be invited to a Persian synagogue where they weren’t comfortable having a woman chant this music. But I'm also not attempting to come to spaces where that would be uncomfortable for people.

I grew up in an egalitarian environment. My Persian father grew up in Iran until 19. He became a cantor in the Ashkenazi tradition.So I grew up in a very Ashkenazi [and egalitarian/Conservative] environment, where women were treated as equals to men in the religious context. So there were no boundaries for me. It wasn't until I was older—in my 20s—that I started immersing myself into Middle Eastern music. At that point, I was very comfortable with Jewish sacred music. Of course this was Ashkenazi music. Making the transition into Persian sacred music— once I had already studied Arab music a bit —was kind of a natural progression to me. I already knew how to chant from the Torah in Ashkenazi style. I studied Persian classical music. When I was, like, 30, I said, “I’m ready” to my dad. “I’m ready to learn the Persian trope.” It was just learning a new trope. Ever since I learned to chant in the Persian tradition I never looked back. It was just very exciting to be able to delve into this heritage, which I was very disconnected from throughout my Jewish upbringing. And my dad, because he was a cantor, was like, “Yeah, you should learn how to do this.” No boundaries!

I had kind of a strange existence in that I didn’t grow up as many people who are immersed in the Sephardi-Mizrahi world did. I wasn’t sitting in the women’s section. I grew up thinking I could do everything men could. I started leading services professionally in my 20s. Making this transition has been a slow and exciting progression. and I haven’t felt limited, just because of my own journey and because of the interesting trajectory I came from.

JWA: What is the controlled voice crack you’re doing in some of these songs?

GD: That’s a part of Persian classical music called tahrir. There are some places in Iraq and Afghanistan where you find that style of music, and that was very exciting for me to learn how to do. That was something I really had to study when I studied Persian music—how to make that sound come from my body. And the way I did it, I couldn’t quite get it until my teacher said, “It’s like crying.” For some reason, that clicked, because I could feel it in my body. It’s just music from that region is called avaz—it’s part of avaz singing.

JWA: What role did the Persian dastgāh [musical system] play in your composition of some of your solo songs on the album?

GD: I have a teacher of Persian classical music and for some of the things that I wanted to solo on I tried to base the song in the dastgah [Persian musical system and trajectory of notes] that I felt were in the correct gusheh [mood of musical movement with set notes]. A gusheh is a small part of each dastgah—about 3-4 notes. It's all connected to the dastgah system but some of this Jewish music…it’s hard to pin down what dastgah you're singing in. It doesn’t always fit perfectly. All of this is based on Persian classical music. And that's really the point: If you hear this music, it’s very Persian. I wanted people to hear this album and go, “This is both Jewish and very Persian at the same time.” “Wine Song for Spring” is in Mahur [a Persian musical mood], which is light, happy, and springy. I think about what I’m going for first, and then compose the song, and then think about things like what makam [musical system] it’s in later—I didn’t start by figuring out the mode.

JWA: What was the most emotional song to work on from the album? Also, do you have a secret favorite song on the album?

GD: Regarding emotional: definitely “Anenu.” The words are emotional. It's all about asking God to answer us, and reminding God of all of these different characters. Father of Abraham—all of these different characters—please answer us, God. More importantly, I’m able to trade verses with my grandfather with this technology, and singing each time after hearing him sing a verse is always very emotional for me on stage. We’re responding to each other. So singing that piece, that’s always the most emotional moment for me.

I don’t have a favorite song on the album. One thing that I was excited about with this project is that, because my grandfather did these innovations, I took some artistic license and so I made connections to the Persian New Year of Nowruz, which is also a time of renewal. There are very similar themes [to the Jewish Near Year]—except it’s springtime! The whole idea of renewal is so important in the Jewish New Year, and so talking about flowers blooming, and the images of spring, made sense. So I really loved the idea of taking a Jewish song about spring. I found a poet who did “Wine Song for Spring,” and I love that song because it’s not from the Selichot repertoire but I brought it in and composed it. I also love singing with my grandfather on “Adonai hu ha elohim.” But that question—it’s like asking you to pick your favorite child!