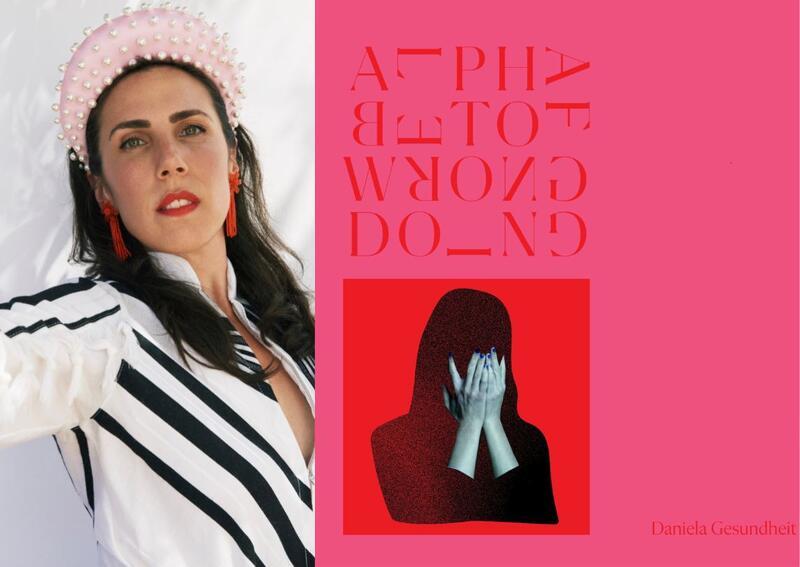

Q & A with Daniela Gesundheit About her New Album, "Alphabet of Wrongdoing"

On September 23, 2022, Canadian musician, vocalist, and composer Daniela Gesundheit shared her latest studio recording, Alphabet of Wrongdoing, with a limited-edition 2LP box set featuring a 108-page hardcover libretto.

Alphabet of Wrongdoing is a gorgeous re-imagining of the High Holidays liturgy, bringing a new perspective to the generations-old prayers of the Jewish people. Listen and you’ll hear everything from chamber folk, ambient electronica, and New Age experimental music in it. Though based in prayer, the themes in Alphabet of Wrongdoing explore the universal human experience, which applies to all of us.

Outside of her recorded music, Gesundheit serves as a cantor for Shir Libeynu, the first queer-inclusive synagogue in Toronto, and officiates life cycle rituals throughout the US and Canada.

Gesundheit sat down with the Jewish Women’s Archive to talk about the album, Jewish sacred music, and her dual role as synagogue clergy-member and touring musician.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

JWA: Mazel tov on your release day, first of all!

Daniela: Thank you so much!

JWA: How does it feel to have the album out in the world?

Daniela: It feels good! I've got baby twins at home, and I was putting them down for their nap this morning and I had a moment to sort of take it in. I was like, this feels good! It's out there, there's some really lovely response coming back. It just feels great.

JWA: Tell me a little about your history with music, sacred and secular.

Daniela: I’ve been singing ever since I could talk. It's been part of my life forever. And I studied music at Wesleyan University in undergrad. But, vocally, I didn't really train. I was more interested in composition and that sort of thing. So my voice got to stay untrained, kind of.

And then, towards the end of university, I started studying privately with cantors in the Bay Area and learned all the High Holiday repertoire, and then learned how to officiate Jewish rituals, life cycle rituals, that kind of thing. And then I worked as a songwriter, a touring musician, for over a decade alongside that. I served as a cantor for the first queer-inclusive shul in Toronto—they're called Shir Libenyu.

I’ve had kind of a double path in music. And I kept the two quite separate that whole time, and only with this record did I try to join the two worlds and see what that would be about.

JWA: Did you always have an interest in the clergy, or is that something that came later?

Daniela: Yeah…no [laughs]. I had an interest in the poetry of Judaism, and the poetry of religious practice, the poetry of these sacred moments in our life. And I had an interest in the music of Jewish tradition.

Growing up, I always felt a little bit alienated in shul. I would try to leave the room to walk around. But I grew to appreciate it and love it, and I definitely feel that being clergy, in a way, is a good fit for me. I think I feel most comfortable in places that are open to questions.

JWA: Could you say a little bit more about the poetry of the language and the music of this tradition?

Daniela: Something that comes to mind is that the shul that I work for, for the High Holidays, we use Richard Levy's machzor, his prayer book for the High Holidays, called "On Wings of Awe." And some of his translations of Kol Nidre and all the prayers that we're about to hear in the coming weeks—he had a way with words where I was sort of spotting these haikus within the prayers. Because Jewish liturgy is lengthy. There are many, many pages, many, many words. It's a lot of noise, a lot of language to wrestle with. The Torah is so long!

But I kept finding these little excerpts that, if I just isolated them, were so resonant for me. One that comes to mind is, "We take nothing away, like a vapor." Another was, "All my bones shall say incomparable." There were all these moments where I was just like, This is what we're singing? This is why we stand up, sit down, stand up, sit down in shul? That's what we're saying?

So there were many, many moments like that, and when you pair that with music and singing, and singing these same melodies for hundreds of years, thousands of years, in community—the magic of it is really palpable.

JWA: How do you feel that your creative process changes shape or looks similar when you're working with existing texts and melodies that have existed for hundreds of years versus when you're working on original music?

Daniela: Oh, yeah. It's so different. It feels like there's much more pressure, working on the Jewish stuff. People have such attachment to it, understandably. I get a kind of—not a stage fright fear, it's a very different kind of fear. It's more of an existential fear, like, I don't want to get it wrong. I don't really get stage fright performing my songwriting work so much, but whenever I would be called to the Torah I got this trembling-in-my-bones kind of fear.

I don't know…I think it has something to do with the fact that words are so important to Jews and to Judaism, and what we say and how we say them— our utterances—are understood to be performative acts. So there's so much reverence given to words and you can feel that as you step into that space. Whereas when I write songs, I bring that same attention to it, but I don't necessarily have a context to bring it into that gives it as much attention and—I don't want to say power, it's something different. But to take a song, no matter how much spirit or how important I think it is to bring it into a bar where people are chatting, it doesn't have the same action, I guess.

JWA: You can really feel on each track the attention to that energy, of how it makes you feel inside when you're singing these sacred texts. Even out of context, you can really feel that. Can you talk about creating that mood and what it was like to make literal what is figurative?

Daniela: I treated the production of the record kind of like casting. Each prayer, I was like, "What is the seam here? Where are we? What are we trying to do? What is trying to be communicated?" And then I cast different musicians based on that. So, in part, I cast the actual instrument—like, oh, this needs a bass saxophone, or this needs a harp. But more specifically, I chose people. Personalities, and musical personalities that I thought would really bring something.

The only thing that was composed for the musicians were the strings.There were string arrangements by Owen Pallett for the Macedonian String Orchestra. But everyone else who appears on the record, I gave them a poetic description and then they improvised and they brought what they wanted to the table. That's how I approached it—very impressionistically.

JWA: It's beautiful, and I feel like it's really evocative of Judaism as collective practice, as something we do together. Can you talk more about the collaborative aspect of the album?

Daniela: I'm so glad you asked that, because it is— it's a highly collaborative album. I began the album with my ex-husband, actually, and we made what we thought were demos that ended up being the sort of bones of the record. And then from there, I started collaborating more and more with my current collaborator, Johnny Spence, who lives in Toronto. He added synthesizers and gave it a distinctive sound.

And then there were almost a dozen musicians on it, a lot of them from the Toronto music scene, the Canadian music scene, and just so many people brought their spirit to it. I found myself consulting everyone who came into the room—consulting their musicality and their humanity while we were making the record. And there were lots of surprises!

JWA: Tell me about some of the surprises!

Daniela: One that comes to mind is Avinu Malkeinu. I think we ended up having—it was guitar and synthesizer. My friend Alex Lukashevsky, we recorded ten of him, so we'd have a minyan of male voices.

JWA: Oh, wow.

Daniela: Yeah! It started to feel almost like a wrestling match, the way the arrangements came together. There were these sort of softer elements, like my voice, and the nylon string guitar. And then there were these more aggressive, typically masculine elements. I felt like there was a kind of wrestling match happening, and at the end, there's no clear victor, but there is a tension created that doesn't get resolved. That, to me, represents a kind of wrestling with patriarchy, or wrestling with our tradition as we've known it.

JWA: As a woman in music and a woman in the clergy, how do you think your voice and perspective specifically impacts the work you put out?

Daniela: I think I have a very natural, very soft-spoken kind of voice that for many people feels surprising in a Jewish ritual context, because it's not an operatic voice. It's not up there declaring. I'm kind of more interested in listening, even as I'm singing, for what is going on in the room, what are other voices in the room doing. And I think a lot of people are, unfortunately, used to going to shul and just taking it in, and not really bringing too much of themselves into the room.

And then in songwriting, in that world, I'm not sure. I think the way people have reflected back to me—there's heart-opening. It's hard to say. Everyone experiences it so differently.

JWA: How does your Jewishness impact your musicianship and how does your musicianship impact your Jewishness?

Daniela: I think my Jewishness impacted my musicianship by showing me the power of collective song, and collective singing, and also using our voices and our music towards some shared goal, that it's not always an individualistic pursuit. It's not always about centering ourselves. It's often about standing together, facing this other shared goal, and using our voices towards that. I took into music from Judaism that [music] can be a sacred act. Of course, music is entertainment as well. But it also can be quite special and holy.

And then, on the other side, I think just a rigorous musicianship felt really satisfying to bring into Jewish spaces. Because I think it's understandably not always the top priority. People love hearing music at shul, but that's not the be all and end all, whereas to get a degree in music or to be out in the world as a musician, that is the thing that you're presenting and that's it. So if that doesn't cut it, it doesn't fly. I think having sort of cut my teeth out in the world that way, it felt really satisfying to bring that caliber of musicianship into Jewish music, and to sort of say, This can sound and feel as good as our favorite pop song.

JWA: Ideally, who are you trying to reach with this album?

Daniela: I keep getting this image in my head of a volcano when it erupts. You just send out lava, and you don't know where it's going to land, and depending on where it lands it turns into different types of rock, depending on the circumstances where it lands. I just know I had to do this, and I'm curious to see where it lands. I want to reach Jews of all kinds, of course. I want to reach non-Jews of all kinds. Not in any sort of proselytize-y way, but just in a, "I have something to share, maybe you'd be interested."

And also in the way of, like, I listen to gospel music, and I listen to South Indian classical music—that's all devotional. There's a lot of tolerance for devotional music in mainstream pop culture, and very little exposure to Jewish music in those same streams. I'm interested in people broadening their ears a bit.

JWA: Do you have a favorite track on the album that you want to dig into before we end?

Daniela: I think "Alphabet of Wrongdoing," the title track of the album. It's one that almost any Jew who has been to shul ever would know. It's recited on Yom Kippur, and it's a list of all the wrongdoings of the past year in alphabetical order, and on every utterance you beat your chest. And it's a really beautiful instance of communal atonement, which is kind of particular to Judaism where it's not this solo responsibility. It's a community responsibility, and that even if you haven't bribed [someone] or stolen this year, someone around you may have. And to recite this together anonymously opens up space for people to feel okay to face these parts of themselves.

But it always struck me, every year, as I was singing it. It's such a heavy theme, and you're beating your chest, but it has such a sing-songy—at least in Ashkenazi tradition—it has such a sing-songy melody. It sounded, to me, like, is this a little tongue-in-cheek? Did the rabbis of the past—were they like, we have to keep some levity? It can't all be serious all the time. So it really resonated with me. I feel like it speaks to my heart of, like, life is serious and hard and painful, and we have to atone and reckon. But also, we need to laugh. We need to let loose a bit.