Loolwa Khazzoom on her new single, "The Convert's Quest"

In their new single “The Convert’s Quest,” Loolwa Khazzoom’s rock band Iraqis in Pajamas calls for an end to what she dubs “anti-convert hostility.” The single is being released on May 24, just in time for Shavuot (Shbu’oth, in Judeo-Arabic), the holiday on which we read the Book of Ruth; many consider Ruth the original “Jew by choice.”

Jewish tradition actively embraces those who pursue conversion, with an injunction that once someone converts, that person is simply a “Jew,” not a “convert.” Nevertheless, Loolwa has observed a trend of anti-convert hostility, with Jewish community members claiming that converts “are not real Jews”—in particular, those who converted through denominations that don’t require immersion in the mikvah. (Interestingly, Ruth did not do the ritual immersion, which today is required to be considered a verified convert in the Orthodox movement.) As a result, those attempting to convert to Judaism, and those who have converted, may find themselves facing antagonism and rejection.

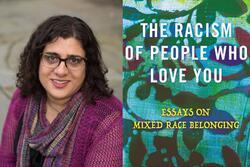

Loolwa Khazzoom is the daughter of an Iraqi Jew on one side and a Jew by choice on the other. Her background has given her first-hand experience in the fluidity of Jewish identity and the key role that converts play in awakening and transmitting the heart, soul, and passion of Judaism. Disheartened when she noticed negative treatment of Jewish converts, Khazzoom wrote “The Convert’s Quest” to challenge the anti-convert sentiment through a Jewish lens. The new single is a passionate epic, both spiritual and deeply grounded in its message and its rock musicality. You will learn something and feel something all at once.

JWA spoke to Loolwa about her identity, her Judaism, and her new single.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

JWA: Can you talk about how your upbringing impacts the way you experience Judaism?

Loolwa Khazzoom: I have a really unique vantage point, because my dad was an Iraqi Jewish refugee from one of the most ancient diaspora communities. And people don't think—they don't connect the biblical stories with the contemporary maps.

On the other side, my mom is Jew by choice, so I'm a first-generation born Jew.

JWA: Your music is so unique. I love that it blends the ancient with the modern: rock combined with sacred music, older languages with what feels more up-to-date. It makes me think about how conversion is as old as Judaism and as new as the last person to become a Jew by choice. Could you talk about that intersection in your music—drawing lines between what’s old and what’s new?

LK: Well, that's really interesting that you asked that, because a long time ago, back in the ’90s, there was an organization that shall remain unnamed that was picking my brain about Jewish multiculturalism. And the critique that I gave them was that all their material was talking about the “new face of the Jewish community,” and their whole shtick was that because people are converting, and because people are adopting kids from China or Africa, that now we have Jews of color. And I was like, are you aware we have had Jews of color for thousands of years? It was ridiculous. We were in Africa and Asia way before we were in Europe.

JWA: What do you wish the broader Jewish community understood about Jewish multiculturalism?

LK: It's almost like there's an amnesia of sorts for Jews of European heritage. It's like everything that's in the holidays they're celebrating seems like it's from a fantasy storybook as opposed to a real place and a real time. We recently celebrated Pesach, which is from Egypt, and back in the early ’90s, when I would give workshops, I was like, “So, hey, how many of you know how Egyptian Jews celebrate Passover?” And nobody raised their hand. We might want to think about that. We are from everywhere. We intersect and crisscross.

I think conversion really emphasizes and challenges the validity of identity and challenges all these divisions that are going around today, which I think are false divisions between humanity.

Abraham and Sarah, they didn't just cross over the Euphrates River; they crossed over a belief. They’re your original converts. We came from another religion; we came from idol-worshiping, and you had to start somewhere. So, who is in a position to say, “Oh, only these people get to start somewhere? Nobody else gets to start somewhere—you have to already have lineage.”

It’s something that was just pervasive, and I think that over the decades, that consciousness has shifted. But it just never ceases to amaze me.

JWA: I want to ask you about Ruth and her role in your belief system and your music.

LK: Something I like to point out is that Ruth would not be accepted in any number of Orthodox Jewish schools today. Technically, by those standards, Ruth never became a Jew.

I think converts are the most flaming Jews. I am such a flaming, unapologetic, in-your-face Jew. And I'm the daughter of a convert. And I don't think that's unrelated. So many Jews would give up being Jewish because they're tired of anything from harassment to persecution; they're tired of being different. They're tired of it. And converts know this going in, and they choose it. Yeah… they know this going in, and they choose it. That is glorious. They are reminding us of the soul of Judaism and what is so beautiful about our heritage.

JWA: How does your Judaism inform your music? How does your music inform your Judaism?

LK: I was born a musician. My mom tells me that I started singing before I started talking. Apparently, when I was three months old, she was driving somewhere, and I'm in the back in a bassinet. And all of a sudden, I started—she called it singing. I never thought to ask her, like, did she mean humming? But I started singing one of the songs that we sing on Shabbat. And she looked in the rearview mirror, and she was so shocked. She said I was swaying back and forth, and super happy. I'm just, like, belting it out.

When I was eight years old, I learned how to lead the prayers. And I could do it from start to finish, you know, in the Iraqi accent, which, in my generation—I'm 54 this summer, so this is growing up in the ’70s. None of the kids were learning this because everybody was busy trying to be Ashkenazi. It was not cool back then. My parents were really bucking the trend.

It was very frustrating as a girl, because I was rejected constantly in synagogue and told to sit behind [the men], shut up. And I literally when I was fourteen—that's a whole other story— but I stormed the men’s section and got the women drowning out the men.

So, music for me is my path to God. It is my expression of Judaism; it is my expression of my love for Judaism. It is the transmission of my lineage.