Anna Sokolow

This web exhibit was made possible by a generous donation from the Rosh Foundation.

"I felt a deep social sense about what I wanted to express, and the things that affected me deeply personally [are] what I did, and commented on."

Anna Sokolow was a dancer and choreographer of uncompromising integrity. Believing strongly that dance could be more than mere entertainment, she explored the most pressing issues of her day—from the Great Depression, to the Holocaust, to the alienated youth of the 1960s—and challenged her audiences to think deeply about themselves and their society.

From Bullfight, a film by Shirley Clarke, 1955.

This film is the only extant recording of Anna Sokolow performing.

Courtesy of Wendy Clarke.

A key figure in the development of modern dance in both Israel and Mexico, Sokolow worked in numerous countries, from Holland to Japan. She also worked with a variety of theater forms; in addition to regular involvement with both Broadway and off-Broadway stage productions, she often experimented with combining dance, mime and the spoken word into a single piece.

Sokolow frequently found inspiration in Jewish history and culture. Not only did her upbringing amidst the left-wing movements of New York's Jewish immigrant communities shape her interest in social and political injustices, but Biblical and modern Jewish figures, Jewish rituals, and other Jewish themes formed the basis of diverse compositions.

Sokolow's compositions were generally abstract; rather than following a narrative structure, they searched for truth in movement and examined a broad range of human emotions. Exploring as they did many of the social, political, and human conflicts that characterize life in the modern world, they often left viewers feeling shaken and disturbed. But even when dealing with the darkest of subjects, Sokolow's appreciation of the dignity of the human spirit and its resilience in the face of trouble and despair was evident. As a reviewer wrote in 1967, "Miss Sokolow cares—if only to the extent of pointing out that the world is bleeding. I find hope in such pessimism."

Notes:

- Opening quotation from Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, prod. and dir. Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, 20 mins, 1980, videocassette. First Dance Horizons Video release, 1991.

- Quotation beginning "Miss Sokolow cares?" from Clive Barnes, "Dance: Pity Without Sentimentality," New York Times, March 12, 1967.

Early Years

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, from their film Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, produced in 1980.

Anna Sokolow was born on February 9, 1910, in Hartford, CT, to Sarah (Kagan) and Samuel Sokolow. Recent immigrants from Pinsk, the Sokolows had difficulty adjusting to life in America. As Anna later recalled, "In the European Jewish tradition, the man was really the scholar, and the woman he married and her family took care of him and their children. When they came here, a lot of them had to change.... They learned to cope with the system and realized that they had to earn a living. Well, my father was totally bewildered by it.... Eventually my mother, with her great energy, stepped in and took over."

[jwa_media:10160:class=float-none]In the early 1910s, the Sokolows, now with four children, moved to New York City. Sarah found work in the garment industry, but Samuel soon became ill with Parkinson's disease, and Sarah had to place him in a charity hospital. She also put her youngest daughter, Gertie, in a Jewish orphanage for several years; her son, Isidore, dropped out of school to contribute to the family income.

Despite the hardships, Sarah retained her strong will and high spirits. Attracted to the Socialist Party and trade unions by their acceptance of women as valued participants, she attended political meetings, joined the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, and took part in union solidarity marches, sometimes bringing her daughters.

Anna inherited her mother's comfort with unconventionality and her commitment to social and economic activism. She also soaked up the vibrant Jewish culture that surrounded her. Sarah regularly took her children to Workman's Circle dances and the Yiddish theater, in addition to keeping a kosher kitchen, observing Jewish holidays, and lighting Shabbat candles every Friday night. The Lower East Side environment proved a significant influence on Sokolow's later work.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "In the European Jewish tradition?" cited in Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 2.

- Remaining information from Warren, 2-6, and Interview with Anna Sokolow by Barbara Newman, December 1974-May 1975, for Oral History Project of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center.

Madly in Love with Dancing

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, from their film Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, produced in 1980.

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, from their film Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, produced in 1980.

At about the age of ten, Anna began attending classes sponsored by the Emanuel Sisterhood of Personal Service, together with her older sister Rose. Sarah Sokolow was extremely concerned that her young children never be left alone without supervision, and the Sisterhood provided a safe haven for them at lunch breaks and after school. There, in a class on interpretive dance in the style of dance pioneer Isadora Duncan, Anna quickly "fell madly in love with dancing."

By the time Anna was 15, the Sisterhood dance teachers had taught her all they could. Recognizing her promise, they sent her to continue her training at the Neighborhood Playhouse, one of the first important "Off-Broadway" theaters, then housed at the Henry Street Settlement House. At about this time, Anna also dropped out of school and left home. She supported herself by taking odd jobs, including working in a factory tying teabags.

At the Neighborhood Playhouse, Sokolow studied with such important early modern dance figures as Blanche Talmud and Bird Larson; she also took classes in pantomime, diction, and voice. When the Playhouse left the Henry Street Settlement House in 1928 and opened a fully professional School of the Theatre, Sokolow was given a full scholarship and invited to join the school's Junior Festival Players. Highly respected performers and teachers taught the students movement, singing, diction, and theater craft, while dancer Martha Graham and composer Louis Horst revolutionized the Playhouse's dance training. Sokolow's later attempts to bring together various theater forms grew out of her early training at the Neighborhood Playhouse.

Notes:

- Quotation "fell madly in love with dancing" cited in Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 7.

- Remaining information from Warren, 6-9, 13-17; Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, prod. and dir. Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, 20 mins, 1980, videocassette; first Dance Horizons Video release, 1991.

Martha Graham & Louis Horst

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, from their film Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, produced in 1980.

After finishing her training at the Neighborhood Playhouse, Sokolow joined Martha Graham's new professional dance company in late 1929. For much of the next decade, she studied and danced with Graham, participating in such notable works as Primitive Mysteries (1931) and Celebration (1934) and in Graham's first tour. "It was staggering," Sokolow later recalled. "I just knew I was in the presence of something great."

The relationship between Sokolow and Graham, however, was often difficult. Graham demanded unquestioning loyalty from her dancers, who worked nonstop for no pay, praise, or encouragement, and Sokolow, as she herself said, did not "have the temperament of a disciple." Sokolow's interest in exploring her own Russian-Jewish background clashed with Graham's focus on Americana, and her efforts to strike out in her own direction found little support from Graham. Sokolow left the company with some bitterness in approximately 1938. Only much later was she fully able to acknowledge Graham's abilities: "Now, at my age, and with everything I've done," she wrote in the 1990s, "I [have] begun to realize what a great artist Martha Graham was."

Sokolow always insisted that Louis Horst, Graham's accompanist and composer, was a far greater influence on her development than Graham herself. Horst taught choreography at the Neighborhood Playhouse, and Sokolow was his most promising student. For several years, she earned $25 a week as his assistant, becoming known as "Louis' Whip." Horst not only imbued in her a thorough appreciation of both music and dance forms, he also encouraged her to explore her own ideas in her compositions. "The way I found out [who I was] was not with Martha Graham," she remarked later, "but with Louis Horst." For decades, Sokolow looked to Horst for approval.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "It was staggering..." from Interview with Anna Sokolow by Barbara Newman, December 1974-May 1975, for Oral History Project of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center.

- Quotation "have the temperament of a disciple" from Dance on: Anna Sokolow, Prod. Billie Mahoney, 1981.

- Quotation beginning "Now, at my age..." cited in Robert Tracy, Goddess: Martha Graham's Dancers Remember (New York: Limelight Editions, 1997), 27.

- Quotation begnning "The way I found out...." from Interview with Anna Sokolow, 1974-75.

- Remaining information from Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 19-21; Interview with Anna Sokolow, 1974-5; and "Agnes de Mille talks about Anna Sokolow and Martha Graham," May 31, 1974, in the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Radical Dance

In the early 1930s, while still dancing for Graham, Sokolow began to work with other groups and to choreograph pieces of her own. As did many other Jewish women dancers, she became associated with a loose coalition known as the "radical dance" movement.

Although modern dancers had always believed dance should be more than mere entertainment, Sokolow and her contemporaries searched for a new, revolutionary approach. Unlike early modern dance pioneers, who often looked to ancient myths and timeless legends, the "radical dancers" saw their art as a potential agent of societal change and found inspiration in events around them. Disturbed by the upheavals of the Depression at home and the rising threat of fascism abroad, they tried to raise consciousness by dramatizing the economic, social, and political crises of their time. Audience members, they hoped, would in turn be inspired to help resolve these crises.

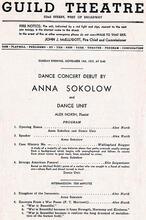

Sokolow's first major composition for a group, Anti-War Trilogy, was performed at the 1933 First Anti-War Congress, sponsored by the American League Against War and Fascism. She continued to portray the dangers of war and fascism in such works as Inquisition '36, Excerpts from a War Poem, and Slaughter of the Innocents. She also examined the oppression of industrial workers (Strange American Funeral), analyzed juvenile delinquency (Case History No.--), and satirized modern society (Romantic Dances, Histrionics).

By the mid-1930s, Sokolow was the youngest American choreographer to lead her own professional dance group, "Dance Unit." In 1936, she staged the first full-evening concert of her own works at New York's 92nd Street Y.

In 1934, Sokolow traveled to the Soviet Union, where she hoped to find a truly revolutionary dance movement. She was disappointed to discover that Soviet dance was in fact less avant-garde than the American "radical dance" movement.

Notes:

- Information drawn from Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 23-61; Nancy Brooks Schmitz, "Catherine Littlefield and Anna Sokolow: Artists Reflecting Society of the 1930s," Dance: Current Selected Research (1989): 115-123; Stacey Prickett, "Dance and the Workers' Struggle," Dance Research (Spring 1990): 47-61.

Mexico

In the spring of 1939, Mexican painter Carlos Mérida saw Sokolow and her "Dance Unit" perform in New York. Deeply impressed, he immediately invited them to Mexico.

Despite the fact that little modern dance existed in Mexico, Sokolow's work was an immediate success. People of all classes—from peasants to professionals—flocked to the performances, the number of which was increased from six to twenty-three. Asked to work toward the creation of a government-sponsored modern dance company, Sokolow remained in Mexico when her dancers returned to New York. After eight months of intense work, the members of the Ballet Bellas Artes (Fine Arts Ballet) debuted in March 1940. Shortly thereafter, Sokolow helped to form La Paloma Azul (The Blue Dove), a group that brought together dancers, artists and musicians.

Despite critical acclaim, La Paloma Azul did not survive beyond its first season. Yet Sokolow's work laid the foundations for an indigenous Mexican modern dance movement. For decades, her original dancers were referred to as "Las Sokolovas," while she herself became known as "la fundadora de la danza moderna de Mexico," or "the founder of Mexican modern dance."

Mexico also had a profound effect on Sokolow's artistic development. Deeply moved by the Mexican people's reverence for art, she also felt a strong affinity for Mexico's artistic community, including Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and Silvestre Revueltas. "For the first time in my life," she said, "I knew what it felt like to be an artist." Sokolow created a number of pieces on Mexican and Spanish themes, and a new lyricism appeared in her work. For nine years, she commuted between Mexico City and New York, acknowledging with reluctance that her true creative roots lay in New York.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "For the first time in my life" from Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes (interviewers), Outtakes from the film They Are Their Own Gifts, December 17, 1975, cited in Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 69.

- Remaining information from Warren, 63-74, and Doris Hering, "My Roots are Here," Dance Magazine, June 1955, 36.

Jewish Dance

Courtesy of Hadassah Segal.

Anna Sokolow's Players' Project performing Sokolow's Dreams, 1977.

Courtesy of the Sokolow Dance Foundation.

Prior to her stay in Mexico, Sokolow created only one piece with clear Jewish content, the 1939 The Exile. In part influenced by the strong role of religion in Mexican culture, she began to draw more frequently on Jewish history, religion, culture, and society in her work.

Many of Sokolow's Jewish compositions explored themes of exile and suffering, as did her work as a whole. Her 1945 Kaddish, choreographed just as the Holocaust ended, drew upon traditional Jewish elements to express her intense pain and sorrow. Beating her breast and invoking tefillin by wrapping a leather strap around her arm, Sokolow created a heartwrenching manifestation of mourning. Her Dreams, premiered in 1961, was the first serious dance exploration of the Holocaust.

Yet Sokolow did not simply mourn for a lost culture and a lost population. Many of her pieces explored the Jewish people's strength and courage in the face of great adversity; others commented upon Jewish religious and social traditions. Sokolow based a number of works specifically on Jewish female figures, from the Biblical Ruth, Miriam, and Deborah to the modern Hannah Senesh and Golda Meir. Her 1943 Songs of a Semite, named after a book of poems by Emma Lazarus, presented a lonely Jewish woman who gained strength from remembering the courage of several Biblical women.

The Jewish community provided Sokolow with opportunity as well as inspiration. Not only did Jewish unions and fraternal organizations form many of her first audiences, but she premiered a number of pieces at New York's 92nd Street Young Men's Hebrew Association. Sokolow also staged festivals and pageants in support of State of Israel bonds and directed a synagogue service combining poetry and dance.

Notes:

- General information drawn from Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998).

- Information about Songs of a Semite from Edwin Denby, "A Modern Dancer—Other Dance Events," New York Herald Tribune, December 12, 1943.

Broadway & Other Venues

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, from their film Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, produced in 1980.

Influenced by her wide-ranging training at the Neighborhood Playhouse, Sokolow never limited herself strictly to dance. In 1935, her Anti-War Cycle appeared on the program with Clifford Odets' play, Waiting for Lefty, strengthening her pre-existing connection to the theater. Soon after, she directed the dances for a Broadway production of André Obey's Noah.

In the late 1930s, Sokolow did the choreography for Sing for Your Supper, a revue staged by the WPA's Federal Theatre Project to put unemployed singers, actors and dancers to work. In 1947, she choreographed the musical version of Elmer Rice's play Street Scene, with a score by Kurt Weill and lyrics by Langston Hughes. Her dances—particularly a duet based on the jitterbug—dramatically heightened the story's effect and broke new ground on Broadway. Asked how she managed to capture so effectively the flavor of the Lower East Side streets, Sokolow replied, "It's simple, when you've been part of them."

Over the next several years, Sokolow staged dances and movement for plays on and off Broadway. Her work ranged from Leonard Bernstein's version of Candide to her own dramatization of Kafka's Metamorphosis. She also choreographed a season for the New York City Center Opera.

In 1967, Sokolow was invited to choreograph the dances for the rock musical Hair. With the director and writers clashing over the staging, Sokolow gradually took on more and more responsibility; by the end of rehearsals, she was serving as director. When the original director returned at the last minute, however, Sokolow was dismissed and much of her staging reworked. Yet she still had a significant impact on the cast and the performance, and consequently on the future of Broadway.

Notes:

- Quotation "It's simple, when you've been part of them" cited in Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 84.

- Remaining information from Warren, 47-48, 59-61, 83-88, 172-175; Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, prod. and dir. Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, 20 mins, 1980, videocassette; first Dance Horizons Video release, 1991; Ezra Goodman, "Broadway Choreographers," Dance (March 1947): 13-15.

Israel

Members of Israel's Springboard Dance Company perform Anna Sokolow's "Tribute to Gertrude Kraus," circa 1995.

Courtesy of the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance.

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, from their film Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, produced in 1980.

In 1951, the America-Israel Cultural Foundation asked choreographer Jerome Robbins to select an Israeli dance group to represent Israeli dance abroad. Robbins chose the Inbal Dance Theatre, a promising Yemenite Jewish ensemble. He realized, however, that the group needed help in raising itself to fully professional standards. Sokolow, who had worked in similar situations in Mexico and displayed a strong interest in Jewish themes, seemed the perfect candidate to take on this task.

Arriving in Israel in 1953, Sokolow was deeply impressed by the Inbal dancers' Yemenite movements and rhythms, their creativity and their dedication. Her challenge, she felt, was to teach them useful techniques and professional habits without meddling with the core of their dancing. Dancers in the new nation struggled with poor working conditions, often using improvised stages as they toured cities and kibbutzim, but Sokolow, having faced similar problems in the early years of her career, was undaunted. After three years of hard work, Inbal made a triumphant European debut.

Recalling her first visit to Israel, Sokolow commented, "I certainly didn't expect to be affected so deeply, but the minute the plane landed I was overwhelmed with an indescribable feeling about being there. I didn't have any kind of strong Zionist background, but going there changed my point of view. [Israel] is now one of the deepest things in my life."

Sokolow returned to Israel virtually every summer for decades, teaching countless groups of dancers and actors. In the early 1960s, she created a new company, the Lyric Theatre, designed to bring theater, music and dance together. Although the company survived only a few years, it helped Israeli modern dancers achieve professional standing and recognition.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "I certainly didn't expect" cited in Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 105.

- Remaining information from Warren, 103-109, 147-154; Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, prod. and dir. Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, 20 mins, 1980, videocassette; first Dance Horizons Video release, 1991.

Choreographic Innovations

Anna Sokolow's players' project performing The Lovers from Sokolow's Magritte, Magritte, 1972.

Courtesy of the Sokolow Dance Foundation.

In 1951, Sokolow staged and performed in a theater-dance production of S. Ansky's play, The Dybbuk. The dramatization represented one of Sokolow's first major attempts to combine dance with mime and the spoken word, a process that had long intrigued her. Following The Dybbuk, Sokolow largely ceased to perform in public, preferring to focus instead on choreography.

Two years later, Sokolow premiered Lyric Suite. Set to a complex, atonal score, the 1953 piece followed neither meter nor melodic line, but rather responded to the music's cumulative effect. Sokolow saw the composition as a personal artistic turning point, commenting that "[i]n working on Lyric Suite I feel as though I began to find...my vocabulary of movement." After viewing the piece, Sokolow's mentor Louis Horst told her, "Now, Anna, you are a choreographer!" It was the highest compliment he could have paid her.

Over the next decades, Sokolow continued to experiment with combinations of music, dance and theater. In such works as Act Without Words (1969), Magritte, Magritte (1970), and From the Diaries of Franz Kafka (1980), she freely mixed mime, acting, dance and music to create a unique and powerful art form. In 1969, she created a new company—called Lyric Theatre, like her short-lived Israeli group—devoted specifically to compositions of this type. As she said, "I prefer to work with people who can dance and act rather than dancers who act or actors who dance." A few years later, the group was reconstituted as The Players' Project. It is now known as the Sokolow Dance Foundation.

Sokolow's choice of music for her pieces was also highly innovative. Working with such composers as Teo Macero and Kenyon Hopkins, she was one of the first choreographers to set her compositions to serious, edgy jazz music. One of these works, Opus '65, became the prototype for countless later "rock ballets."

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "[i]n working on Lyric Suite" from Interview with Anna Sokolow by Barbara Newman, December 1974-May 1975, for Oral History Project of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center.

- Quotation "Now, Anna, you are a choreographer!" cited in Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 114.

- Quotation beginning "I prefer to work with people" cited in Aaron Cohen, "Anna Sokolow is...," undated New York Times clipping from the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

- Remaining information from Warren, 97-98, 111-114, 177-185; Cohen; Interview with Anna Sokolow, 1974-1975.

Prophet of Doom?

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes.

From her early treatment of problems such as juvenile crime, industrial oppression and the horrors of war, Sokolow moved later to more internal conflicts, examining the full range of human emotions engendered by life in contemporary society. As one critic commented, "[I]t is her depictions of the brutal loneliness and despair of urban life that have defined her."

In 1955, Sokolow premiered Rooms, a powerful portrayal of the terrifying loneliness that afflicts even people living in the closest proximity to each other. Unsettled by the work, critic John Martin wrote, "Its ultimate aim seems to be to induce you to jump as inconspicuously as possible into the nearest river." Ten years later, Sokolow completed Opus '65, a vivid depiction of the era's alienated youth culture. The withdrawn sufferers of Rooms now stood as an angry, disaffected group, tired of feeling isolated and disconnected. Yet their efforts at connecting were frightening and left audiences feeling shaken and disturbed.

Critics began to refer to Sokolow as a "prophet of doom." Yet Sokolow's choreography was rarely wholly disheartening or depressing. Rather, she retained a faith in the dignity of the human spirit and the human capacity for endurance that tempered the discomfort her work caused. As Clive Barnes wrote, "No one would go to Miss Sokolow for a good laugh—yet far more importantly no one would go to her for a good cry.... Sokolow's belief in humanity shines through her pessimism. Her pity and her compassion give her taut and tortured dances a justification."

Sokolow, moreover, had a lighter side, and her work could be humorous or lyrical as well as disturbing. A Short Lecture and Demonstration on the Evolution of Ragtime was a delightful spoof of lecture-demonstrations, while pieces such as Ballade displayed a graceful lyricism that contrasted with many of her darker works.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "[I]t is her depictions" from Jennifer Dunning, "From Urban Walks, A New Sokolow Dance," New York Times, October 31, 1991.

- Quotation beginning "Its ultimate aim" from John Martin, "Dance: Study in Despair," New York Times, May 17, 1955.

- Quotation beginning "No one would go" from Clive Barnes, "Dance: Pity Without Sentimentality" and "The Perfect Answer," New York Times, March 12 and March 26, 1967.

Teaching & Rehearsing

When Sokolow began her career in the 1930s, it was virtually impossible to earn a living as a modern dancer. Like most of her colleagues, she supplemented her income by teaching. Joining some of the era's best-known dancers, she taught classes in the Graham technique at New York's 92nd Street Y and the Neighborhood Playhouse. This work did more to support her than did most of her concert appearances.

Sokolow later taught extensively in New York City and around the United States. She also gave workshops and classes and staged works in many countries, including England, the Netherlands, and Japan, as well as in her beloved Mexico and Israel.

In the 1930s, Sokolow began giving classes to the Group Theatre, and she continued to work with actors as well as dancers until the very last years of her life. In the 1940s and '50s, she worked with Elia Kazan at the Actors Studio, and in 1958, she began decades of teaching actors and dancers at the Juilliard Dance Division. "My first aim is to free the actor from his self-consciousness," she once commented. "I make him forget about the cliches about having to smoke, to touch or handle something.... It may seem to the actor that he is learning how to move and how to use his body, but what he really learns is to be simple, honest and human."

A demanding teacher, Sokolow had no patience with dancers she suspected of insincere dramatic projection. Caring little about a particular style or technique, she believed students needed to find their own way and to draw from true emotions. She was often difficult, but students who responded with the passion, intensity, and vulnerabilty she sought earned her respect and became intensely loyal to her. Dancer José Coronado reflected, "I fell in love with the woman, and I followed her like a dog—because of her integrity."

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "I fell in love with" cited in Deborah Jowitt, "Anna at Eighty-Five," Dance Magazine (August 1995): 40.

- Quotation beginning "My first aim" cited in Walter Sorrell, "We Work Toward Freedom," Dance Magazine (January 1964): 52.

Recognitions

At the age of only 27, Sokolow, together with José Límon and Esther Junger, received one of the first fellowships from the Bennington School of the Dance. At a time when most dancers and choreographers subsisted on a shoestring budget, the support provided an important lift to the young choreographer's career.

Over the next decades, Sokolow was often recognized as one of her era's most gifted and innovative choreographers. The citation for a 1961 Dance Magazine award read: "To Anna Sokolow, whose career as concert dancer, choreographer, and teacher in this country and on the international scene has been distinguished by integrity [and] creative boldness, and whose recent concert works have opened the road to a penetratingly human approach to the jazz idiom." In 1967, Sokolow was one of six American choreographers to receive $10,000 grants from the National Council on the Arts (soon to become the National Endowment for the Arts), and in 1988 she was awarded Mexico's highest civilian honor given to a foreigner.

On several occasions, Sokolow's strong interest in Jewish dance and Jewish themes earned her special recognition. In 1975, New York's 92nd Street Y presented her with an award for her contributions to the world of dance and to the Jewish people. Eleven years later, a gala evening in Sokolow's honor opened a three-day conference on "Jews and Judaism in Dance."

In 1991, Sokolow received the Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award, given to those who have made a significant lifetime contribution to American modern dance. In 1995, a star-studded group of dancers, actors and musicians gathered to celebrate Sokolow's 85th birthday with a grand gala of speeches, memories and performances. In 1998, two years before her death, Sokolow was inducted into the National Museum of Dance's Dance Hall of Fame.

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "To Anna Sokolow" from Larry Warren, Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998), 163.

- Remaining information from Warren, passim, and programs and videotapes from "Jews and Judaism in Dance" and Sokolow's 85th Birthday Gala.

Legacy

Courtesy of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center

Courtesy of Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, from their film Anna Sokolow, Choreographer, produced in 1980.

Sokolow never shrank from confronting her audiences with difficult realities. She searched for truth in movement, using dance to explore the broad range of human emotions and encouraging her audiences to think for themselves. "[M]y works never have real endings," she said. "[T]hey just stop and fade out, because I don't believe there is any final solution to the problems of today. All I can do is provoke the audience into an awareness of them."

The conviction that "[a]rt should be a reflection and a comment on contemporary life" shaped Sokolow's entire career. Always animated by an intense social consciousness, Sokolow believed strongly in the necessity of involvement with the world around her. "The artist should belong to his society," she wrote, "yet without feeling that he has to conform to it.... Then, although he belongs to his society, he can change it, presenting it with fresh feelings, fresh ideas."

Sokolow died on March 29, 2000, at the age of 90. Her unique and powerful approach to her art left its mark on students and colleagues, from Robin Williams to Alvin Ailey, and countless amateurs and actors as well as professional dancers remember her lessons with gratitude and admiration. Gerald Arpino, artistic director of the Joffrey Ballet, spoke for many when he paid tribute to Sokolow at her 85th birthday: "I became a dancer because of the pure joy and spirit of dance. I remained in the field ever since because such pioneers as Anna Sokolow showed me the deep commitment and intense humanism that dance is capable of expressing. Her indomitable spirit, her courage, her uncompromising truths are beacons not only for the dance world but for all humankind."

Notes:

- Quotation beginning "My works never have real endings" from Anna Sokolow "The Rebel and the Bourgeois," in Selma Jeanne Cohen, ed., The Modern Dance: Seven Statements of Belief (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1966), 36.

- Quotations beginning "art should be a reflection" and "The artist should belong" from Sokolow, "The Rebel and the Bourgeois," 32-33.

- Quotation beginning "I became a dancer" from The Anna Sokolow 85th Birthday Gala, artistic directors Lorry May and Jim May, 116 min., 1995, videocassette.

Media

Timeline

Born on February 9 in Hartford, CT, to Sarah (Cohen) and Samuel Sokolowski; family moves to New York City a few years later

Takes first dance class, at Emanuel Sisterhood of Personal Service

Studies with Martha Graham and Louis Horst at Neighborhood Playhouse School

Joins Martha Graham's company

Choreographs and performs in first major group piece, Anti-War Trilogy

Travels to Soviet Union, where she is disappointed by the lack of a true revolutionary dance movement

Directs dances for André Obey's Noah, the first of many Broadway collaborations

First full-evening concert of Sokolow's choreography, at 92nd Street Y

With other American modern dancers, boycotts International Dance Festival organized by German government to accompany Berlin Olympics

Travels to Mexico for first time; later becomes known as "the founder of Mexican modern dance."

Premiere of Kaddish, inspired by Jewish mourning ritual

Last major appearance as performer, in her staging of S. Ansky's The Dybbuk

Stages "Purim Jubilee" for Greater New York Committee for State of Israel Bonds

Choreographs Lyric Suite, an artistic turning point in which she finds own language of movement

Begins working with Inbal Dance Theater, initiating a longstanding relationship with Israeli dance world

Premiere of Rooms, groundbreaking work dealing with universality of isolation in modern urban society and one of the first modern dances set to serious, edgy jazz

Premiere of Dreams, an allegory of the terror and hopelessness experienced by victims of the Holocaust

Premiere of Opus '65, a prototype for later rock ballets and a strong influence on Broadway

Creates original dances for Off-Broadway production of Hair

Receives honorary doctorates from Ohio State University and Brandeis University

Receives National Foundation for Jewish Culture's Jewish Cultural Achievement Award

Awarded Mexico's highest civilian honor given to a foreigner

Inducted into National Museum of Dance's Dance Hall of Fame

Dies on March 29 in New York City, at the age of 90

Bibliography

Published Sources

Anna Sokolow. Produced and directed by Marvin Diskin. Video. Amphi Productions, 1990. 30 minutes.

Anna Sokolow, Choreographer. Produced and directed by Margaret Murphy and Lucille Rhodes, 1980. First Dance Horizons release 1991. Video. 20 minutes.

Barnes, Clive. "Dance: Anna Sokolow, Prophet of Doom." New York Times. No date.

——. "Dance: Pity Without Sentimentality." New York Times. March 12, 1967.

——. "The Perfect Answer." New York Times. March 26, 1967.

Church, Marjorie. "Anna Sokolow and Dance Unit." The Dance Observer. December 1937.

Dana, Margery. "Anna Sokolow and Unit Seen in New Solo and Group Dances." Daily Worker. November 10, 1937.

Dance on: Anna Sokolow. Produced by Billie Mahoney. Video. 1981.

Denby, Edwin. "A Modern Dancer—Other Dance Events." New York Herald Tribune. December 12, 1943.

Dunning, Jennifer. "From Urban Walks, A New Sokolow Dance." New York Times. October 13, 1991.

Foulkes, Julia L. "Angels 'Rewolt!': Jewish Women in Modern Dance in the 1930s." American Jewish History 88, no. 2 (June 2000): 233-252.

Goodman, Ezra. "Broadway Choreographers." Dance (March 1947): 13-15.

Harris, Joanna Gewertz. "From Tenement to Theater: Jewish Women as Dance Pioneers: Helen Becker (Tamiris), Anna Sokolow, Sophie Maslow." 45, no. 3 (Summer 1996): 259-276.

Hering, Doris. "My Roots are Here." Dance Magazine (June 1955): 36-38.

Jackson, Naomi. Converging Movements: Modern Dance and Jewish Culture at the 92nd Street Y. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2000.

Jowitt, Deborah. "Anna at Eighty-Five." Dance Magazine (August 1995): 38-43.

——. "Dance calligraphy." Village Voice. November 21, 1968.

Lloyd, Margaret. "Dance is for People." Christian Science Monitor. May 16, 1942.

Martin, John. "The Dance: Romanticism." New York Times. March 5, 1939.

——. "Dance: Study in Despair," New York Times. May 17, 1955.

Prickett, Stacey. "Dance and the Workers' Struggle." Dance Research (Spring 1990): 47-61.

Schmitz, Nancy Brooks. "Catherine Littlefield and Anna Sokolow: Artists Reflecting Society of the 1930s." Dance: Current Selected Research (1989): 115-123.

Sokolow, Anna. "The Rebel and the Bourgeois." In The Modern Dance: Seven Statements of Belief, ed. Selma Jeanne Cohen. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1966.

Sorrell, Walter. "We Work Toward Freedom." Dance Magazine (January 1964): 52-53, 73.

Tracy, Robert. Goddess: Martha Graham's Dancers Remember. New York: Limelight Editions, 1997.

Warren, Larry. Anna Sokolow: The Rebellious Spirit. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998.

Unpublished Sources

Sokolow, Anna. Interview by Barbara Newman, December 1974-May 1975. Oral History Project of the Dance Collection of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

"Agnes de Mille talks about Anna Sokolow and Martha Graham." May 31, 1974. In the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Archival Sources

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Jerome Robbins Dance Division: Clippings files, programs, videos of performances and interviews, articles, photographs, and oral histories about or referencing Anna Sokolow.

92nd Street Y Archives: Programs and press clippings from Anna Sokolow's appearances at the 92nd Street Y.

I am writing a paper about Anna Sokolow, and I'd like to inform you that you got her opening quote wrong. The corrected version is the following:

"I felt a deep social sense about what I wanted to express and whatever affected me deeply, personally, I commented on through dance." -Anna Sokolow

I watched the same video that is quoted in your notes section, but that is what she actually says (meaning what I have written above).

She was an absolutely fabulous women. My other favorite quote of hers is the following: "To young dancers, I want to say: 'Do what you feel you are, not what you think you ought to be Go ahead and be a bastard. Then you can be an artist.'" (from The Modern Dance: Seven Statements of Belief, By Selma Jeanne Cohen. Wesleyan University Press. Middletown, 1966. It is Anna Sokolow's quote originally printed under a different title from Dance Magazine in July 1965)