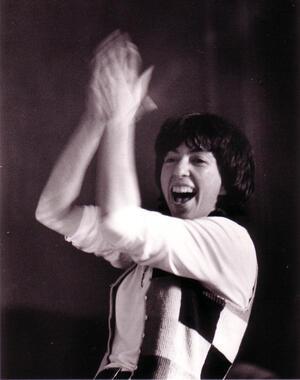

Naomi Weisstein

“Papa don’t lay that shit on me, I ain’t your groovy chick.

Papa don’t lay that shit on me, it’s just about to make me sick.”

—Naomi Weisstein in the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band

Naomi Weisstein was a fierce warrior for justice. She was a passionate disrupter of the existing order. She was a brilliant scientist. She was a fighter for women’s liberation. She was hysterically funny. She had biting insights. She was my beloved friend.

I first met Naomi when I was a student at the University of Chicago in 1963 or ‘64 and she was an adjunct professor in neuro-psychology. Her national reputation preceded her, as one of the first people in the world to help identify how memory worked in the brain. Her brilliance was apparent in almost every conversation and all she wrote. But she couldn’t become a full professor because of the so-called Nepotism Rule that said relatives of professors could not become full professors in order to avoid a conflict of interest in such appointments. Yet the Levi brothers were able to be dean and professor at the same time. The issue was obviously a means of keeping women off of the tenure track and getting wives at a discount rate when husbands were recruited as faculty.

Naomi’s husband Jesse was tenure track. He was a remarkable radical historian who helped teach me and so many others how history was made by the people from the bottom up. He did a pioneering work on the relationship between seafarers’ experiences and revolutionary politics, Jack Tar in the Streets: Merchant Seamen in The Politics of Revolutionary America, showing how life was actually lived by the people most impacted by the history they helped to make.

So we protested the nepotism rule. And we worked together discovering and building women’s liberation voice at the University, in the city of Chicago, and spread it throughout the country.

Jesse and Naomi were a remarkable couple. They mentioned that when they once went to a therapist they were reminded that they were really two separate people and needed to learn how to separate. But they realized while they were separate, they also were deeply, deeply connected and really did feel they were part of each other. They were political and personal partners, in love and in shared struggle in the movement.

On meeting Naomi, I felt electrified. She has such insights, outrageous assessments, and was willing to take bold action for women and a better society.

She brought such wit to her words and actions. When she was younger she had been influenced by Lenny Bruce, the sharp-witted and often caustic comedian challenging conventions and politics as usual of the 1950s. Naomi sometimes described herself as a female Lenny Bruce. But she was not an imitation anything. She was pure Naomi.

We ended up teaching what I think became the first campus women’s liberation session in the country. Naomi and I were part of the West Side Group that may have been the first (or one of the first) women’s liberation groups in the country. We usually met at Jo Freeman’s house on the west side (therefore the name of the group). It was a remarkable and exciting group. The discussions were a bit like intellectual jazz—there was a riffing off of each other’s ideas on a common theme, often going to places that we never imagined we’d go before. And we were all made better and smarter by our working together. Among the people in the group were Amy Kesselman, Vivian Rothstein, Shulamith and Leah Firestone (for a little while), Fran Rominski and others.

We’d go from the group to create action and form other groups.

Out of the effort we helped to convene the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union. A remarkable organization with both work groups (Action Committee for Decent Childcare, Liberation School, abortion counseling with JANE, WITCH, and efforts to organize female janitors at City Hall to win equal pay, high school students, and much more) and home groups for discussion and consciousness raising.

After I graduated and Naomi and Jesse went to work at institutions in other cities, we lost contact with each other. Several years went by and we met in an airport by accident. We connected so deeply that it was as if we had seen each other just the previous week. And again we connected as if we were riffing off each other’s ideas.

We co-authored an article for Sister, the New Haven Women's Liberation monthly magazine, called “Will the Women’s Movement Survive” because we were becoming deeply concerned about the increasingly individual focus of the movement, away from organizing. The movement began with the insight that the personal was political, meaning that problems we thought were ours alone were socially shared and needed a social solution. By the early 1980s this started to shift to looking at individual problems and finding individual solutions—to raise feminists, read non-sexist books to your children, to spread women’s liberation, be liberated in your personal dress and style—all worthwhile, but not a substitute for social and large-scale action.

Again, our lives intervened and we fell out of touch. We lived in different parts of the country and our lives were busy with other things. In the 1980s, at an SDS reunion, I met Amy Kesselman, who told me Naomi had devastating CFIDS (Chronic Fatigue). Because of the vertigo she was on 24-hour bed rest, could not be in a room with lights for very long, and needed round-the-clock nursing care. Because of her illness, she lost mobility in her feet. This very petite firecracker became bloated from her medication. She lost many of her teeth. Lost much of her hair. Her body was destroyed. And still her mind was sharp and her spirit resilient.

Jesse was there for her. He was there to provide care and defend her when she could not defend herself against the insurance companies trying to kick her off their coverage, against the doctors whose treatment (and often mis-treatment) sometimes made her worse, against the landlord who allowed noise that was devastating to Naomi in her condition, and more.

Amy told me that she and her partner, Ginny Blaisdell, called Naomi every weekend and left a phone message for her, even though Naomi was too weak to hear the message and had it retrieved by the nursing staff or Jesse.

I followed Amy’s lead and started calling. And then visiting her every time I made a trip to New York. Naomi was only well enough to visit for about 45 minutes and even then might need a week to recover her strength. We kept doing this for perhaps 20 years.

By my bed, I have a shelf on a bookcase (positioned so that I see it every evening). It is filled with Naomi memorabilia, letters and gifts she sent. Warm and endearing and love-filled. Rants that are filled with biting criticism, pain and anger. A lovely necklace. Beautiful letters. A blue hippopotamus from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Meerkats of many sizes and kinds.

She valued meerkats. They are animals who are fierce defenders of their families and those they care about. They stand guard and watch over them. Naomi was fierce in defense of what and who she loved.

Naomi was often fierce in her anger and hurt. She was sometimes filled with rage. She sometimes lashed out at those close to her. She sometimes drove those who cared away. Perhaps her fighting spirit kept her going.

Even when she was too sick to do much physically, she kept guard mentally and kept up. She wrote. She thought. Her mind and spirit so sharp even when her body was failing.

I came up when she was previously hospitalized with treatment that nearly killed her.

But still she kept on.

Then she found out she had cancer.

And intense pain.

And swelling.

She went to Lenox Hill. It was a horrible experience even with Jesse and his wonderful sisters and two nursing aides providing care.

I came up again.

We laughed and cried and told stories.

We talked about how we would have a party to celebrate when Naomi beat this illness and combine that with celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary.

Just that week I visited, a book was published reissuing the path-breaking research Naomi wrote on aspects of how memory works and where it is located in the brain.

And we told each other how we loved each other.

Naomi said she wanted to live.

She said that if she did not survive this illness and its treatment, she wanted to be remembered for how she loved science, women’s liberation, Jesse, and her friends.

And she wanted us to carry on.

And so we do commit to being fierce warriors for justice. Being passionate disrupters. Remembering Naomi, we carry on with the values and the struggles that she fought and cared about throughout her life.