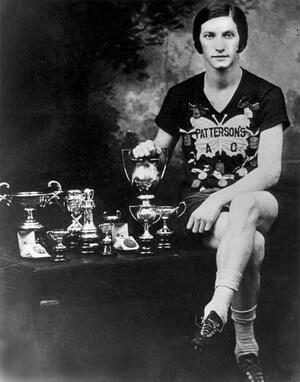

Bobbie Rosenfeld goes for the gold

Bobbie "Fanny" Rosenfeld is recognized as Canada's premiere woman athlete of the first half of the twentieth century. She was an all-round, company-sponsored athlete, a world class track and field champion, an Olympic gold and silver medalist at the 1928 Amsterdam Games and a sports journalist in Toronto for over twenty years. This photograph is from the mid-1920s.

Institution: Canada's Sports Hall of Fame

Even before she won gold and silver medals in the 1928 Olympics, Bobbie Rosenfeld was well known as a star of Canadian track and field. Born Fanny Rosenfeld in Dnepropetrovsk, Russia in 1904, she moved to Canada as an infant; she was later nicknamed "Bobbie" because of her bobbed hair. Growing up in Barrie, Ontario, and then in Toronto, Rosenfeld was an enthusiastic athlete from a young age, playing basketball, softball, hockey and tennis, as well as running. Despite widespread belief that strenuous exercise was damaging to women's bodies, Rosenfeld's family supported her athletic pursuits.

In 1923, Rosenfeld burst onto the national scene when she entered the 100-yard dash at a picnic on a dare from a softball teammate. At the time, Rosenfeld was working in a Toronto chocolate factory. Rosenfeld not only won the race but also beat the Canadian national champion, Rosa Grosse. Two years later, Rosenfeld and Grosse would share the world record for the 100-yard dash, at eleven seconds. Later in 1923, she entered her first major race at the Canadian National Exhibition. In the 100-yard dash, she again beat Grosse and also beat American and world-record holder Helen Filkey. The same evening, after the race, Rosenfeld joined her softball team and helped lead them to the city championship.

Over the next decade, Rosenfeld came to symbolize Canadian women's sport. She went from success to success, leading ice hockey, basketball, and softball teams to championships and winning the Toronto Ladies Grass Courts tennis tournament in 1924. She claimed victory in so many sports that one author later wrote that "the most efficient way to summarize Bobbie Rosenfeld's career ... is to say that she was not good at swimming." A consummate athlete, she was also applauded for her sportsmanship. Both these qualities would soon be evident on the world stage.

In 1928, Rosenfeld was chosen as one of the "matchless six" on the Canadian women's Olympic track and field team. The Olympics of 1928 were the first in which women were allowed to compete in track and field, although only on a trial basis. On July 31, 1928, Rosenfeld won the silver medal in the 100-meter race, though many spectators thought she had actually finished first. A few days later, Rosenfeld competed in the 800-meters, a race in which she had been entered only to encourage teammate Jean Thompson, and for which she had not trained. Coming from the rear, Rosenfeld ran alongside Thompson through most of the race, allowing her teammate to finish fourth while she placed fifth; this was considered a great act of compassion and sportsmanship, as Rosenfeld could easily have pulled ahead and earned a medal in the race. Finally, on the last day of track and field events, Rosenfeld got her gold medal when she led her team to victory in the 400-meter relay. On the team's return to Toronto, 200,000 people lined the streets to cheer a celebratory parade.

Rosenfeld had helped to show that women's competition could be a worthy part of the Olympics; after the Games closed, the delegates of the International Amateur Athletic Federation voted 16-6 to continue women's track and field events at future Olympics. The Canadian delegate voted against women's participation. Back at home, though Rosenfeld had received a hero's welcome, she went back to work at the chocolate factory to pay her bills. In 1928, no endorsement contracts or professional sports opportunities were available to women. Rosenfeld continued to play sports, even starring on championship ice hockey and softball teams, but recurrent attacks of severe arthritis ended her athletic career in 1933. She moved to coaching track and softball, and then, in 1937, to writing about sports. For nearly twenty years, she wrote the "Sports Reel" column for the Toronto Globe and Mail. She retired from the Globe and Mail in 1966 and died on November 14, 1969.

Rosenfeld's legacy is one of breaking down barriers. First as an athlete, and then as the only woman on the sports staff of the Globe and Mail, she carved new paths for women in sports, making it clear to skeptics that, as she put it in a column, "girls are in sports for good." These contributions were recognized both during Rosenfeld's lifetime and after her death. In 1950, a press poll of sportswriters named her Canada's Female Athlete of the Half Century; in 1955, she was among the earliest inductees to Canada's Sports Hall of Fame. Her portrait recently appeared on a Canadian postage stamp, and every year the Bobbie Rosenfeld trophy is awarded to Canada's Female Athlete of the Year.

To learn more about Bobbie Rosenfeld, visit Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia and Women of Valor.

Sources:JWA Bobbie Rosenfeld exhibit, jwa.org/womenofvalor/rosenfeld; New York Times, August 1, 1928; www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/women/002026-236-e.html; http://www.sportshall.ca/latest-news/33020/canadas-sports-hall-of-fame-online-exhibit-celebrates-bobbie-rosenfeld-and-lionel-conacher-award-winners/.

"though many spectators thought she had actually finished first"

The Canadians filed a protest. A "movie machine," as it was called, was used to film the finishes at the 1928 Olympics. It showed Betty Robinson ahead by a foot or so. This is from a dispatch sent shortly after the race. I found this online after some digging.

I hope you'll add the biography I wrote about Bobbie Rosenfeld to your sources: Bobbie Rosenfeld: The Olympian Who Could Do Everything (Toronto: Second Story Press, 2004). ISBN: 9781896764825. In addition, I've created a teacher's guide, which is available on my publisher's website: http://secondstorypress.ca. Thanks very much. Sincerely, Anne Dublin Toronto

In reply to <p>I hope you'll add the by Anne Dublin

Indeed, your book, and a podcast you did about her, are featured on the Encyclopedia page about Bobbie Rosenfeld.

In reply to <p>I hope you'll add the by Anne Dublin

I just went on Amazon and ordered your book. I'm a big fan of Bobbie'!