Sports in the United States

Historians of American sport and of American Jewish history have generally neglected the study of sports by and for Jewish American women. For immigrant women in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, exposure to American life, sport, and physical exercise often occurred at settlement houses and immigrant aid associations. Through the auspices of several Jewish institutions, women and girls participated in sport and physical education for enhancing health, for taking part in Americanization programs, or for engaging in physical recreation deemed appropriate for females. As sport increasingly played a significant role in American society in the twentieth century, it also became part of Jewish women’s experiences in American life.

Introduction

A 1922 publication of the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA) of New York, “How We Serve the Community,” included the theme of physical education, along with dormitory, religious work, and education in the commercial school, trade, and domestic arts. In the physical education category, the YWHA emphasized “Swimming-Tournaments and Contests, Gymnastics, Athletics” at their facility at 31 West 110th Street, New York. Organizers of the YWHA and other Jewish institutions integrated physical activities and sports into programs designed to enhance the experiences of women and girls. However, historians of American sport, and of American Jewish history, have generally neglected the study of sports by and for Jewish American women.

The ways in which females participated in sporting life within both the immigrant and the wider culture reveal how women’s sports activities at times promoted assimilation yet also generated discord within the generational, gender, class, and ethnic context of their lives in the United States.

Immigrant Women and Life in Settlement Houses

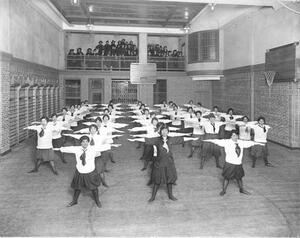

Reformers believed that women needed physical health to fulfill domestic roles and offset the negative influence of unsanitary urban conditions. Physical exercise was the answer, as demonstrated by this 1914 photograph of an exercise class at the Young Women's Hebrew Association in New York City.

Institution: 92nd Street Y, New York

For immigrant women, exposure to American life, sport, and physical exercise often occurred at settlement houses and immigrant aid associations in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. In fact, as Eastern European immigrants came to America and populated urban areas such as New York and Philadelphia, the earlier immigrants, usually German Jews, who by the 1880s had become wealthier and more prominent in American institutions, sought to assist the newest Jewish immigrants by promoting assimilation into American culture rather than nurturing the ethnic identities and religiosity. During the period of widespread Jewish immigration to the United States, 1880 to 1920, philanthropists organized the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA), the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (1902), and the Educational Alliance in New York City to provide for the educational, social, and physical welfare of Jews.

Some women participated in sports at Jewish settlement houses. At the Young Women’s Union in Philadelphia, founded in 1885, Fannie Binswanger and other young women who sought to promote social services for Russian Jewish immigrants introduced recreation and sports to give children a chance to escape the congested city. Women and girls participated in calisthenics and gymnastics. When a new building opened in 1900, girls were instructed in gymnasium class by Caroline Massman and Sadie Kohn. Reorganized as the larger Neighborhood Centre in 1918, the settlement’s new schedule offered additional activities in dramatics, cooking and athletics.

Seeking to promote spiritual and bodily well-being for working-class females, philanthropists who founded the Irene Kaufmann Settlement House in Pittsburgh in 1895 incorporated health and recreational activities in their programs. Known as the IKS, the settlement promoted wholesome physical exercise and athletics in the girls clubs. In I.K.S. Neighbors, the house journal, an article revealed that “Many of our girls have asked for use of the gymnasium and their requests have been granted.” Classes were held for girls of various ages in gymnasium, swimming, basketball and aesthetic dancing. Sporting opportunities for girls and young women at settlements, YMHAs, and YWHAs served as forerunners of organized athletic events of the Jewish community centers most popular in the second half of the twentieth century.

The ideology of sport and physical culture for female immigrants took on gender and class dimensions in the Progressive Era (1900–1920). Social reformers, alarmed at the vice and danger they affiliated with the city life of lower-class immigrants, wanted to offer an alternative and to inculcate youth with American middle-class, white cultural values. Reformers who believed that women needed physical health to fulfill domestic roles and to offset the negative influence of unsanitary urban conditions endorsed physical exercise for women. At Chicago’s Jewish Training School, founded in 1888, immigrant Hilda Satt Polacheck remembered that when she was a young girl, “Gymnastics were taught in a real gymnasium.” With calisthenics and basketball games going on at Hull House, Polacheck said that “the gymnasium was like an oasis in a desert on Halsted Street.”

The Educational Alliance in New York considered physical training and sports for immigrants to be a significant component of the institutional mission. In 1895, the Educational Alliance offered in its “Physical Work” program “male and female classes, [so that] now both young men and young women and children received the benefits of well-regulated physical exercise.” The alliance’s physical culture department conducted “free developing exercises, marching, fancy steps and work with bells, wands, clubs, balls, hoops, horse rings, rope and jumping” for females. The assumption of female gender-appropriate physical exercise meant the emphasis was on forms of health-building sports rather than competition. The goal of such sporting exercises in the settlement house movement centered on “the cultivation of a good carriage” and “the reproducing of better health.”

Sports for Youth

Women social workers and physical culture trainers fostered the use of the gymnasium for girls for purposes of fitness and Americanization. In 1911, Julia Richman suggested to the Committee on Education of the Educational Alliance that the gymnasium be opened on certain afternoons for “girls between the ages of eleven and fifteen, who are wandering aimlessly about the streets and who might be attracted to amusement halls and other places of doubtful influence.” As a counterpoint to the dance halls, saloons, and street life for youth, Educational Alliance physical culture proponents seemed pleased with the Walking Club that sought to “arous[e] girls’ interest in city history and at the same time stimulat[e] in them a desire for healthful outdoor exercise.” Physical education advocates, like the director of the Chicago Jewish Peoples’ Institute, recognized the appeal of sports for youth, asserting, “There is, however, a possibility of injecting a Jewish influence even in the Gymnasium.”

Basketball

Jewish organizations convey a rich history of promoting women’s basketball in intramural and team competition. But the women’s basketball game differed from the men’s version to accommodate concerns that basketball was physically too rough on woman’s constitution. Revised rules avoided physical contact and ensured a team-oriented philosophy with more players on each team. Jewish American immigrant Senda Berenson, known as the “Mother of Women’s Basketball,” became a leading physical educator at Smith College in the 1890s and an avid supporter of women’s sport. She wrote women’s basketball rule books to promote physical vigor and womanly athletic skill. Women’s basketball gained popularity not only in collegiate institutions but also spread to other schools, YWCAs and YWHAs.

Basketball games took place at the Young Women’s Hebrew Association of New York, in programs linking Jewishness with spiritual and physical well-being. Women were required to undergo medical examinations before participating in basketball and other sports so as to avoid potential health risks. The YWHA Physical Training classes for girls included gymnasium exercises and basketball, and when the YWHA moved to its new larger building in 1914, athletic facilities for basketball played an important role. The YWHA touted basketball as “the greatest of all indoor games.” At Chicago’s Jewish Peoples’ Institute, girls played basketball enthusiastically and with excellent ability. They won three girls’ basketball championships in the early 1920s.

Jewish women also excelled in basketball at non-Jewish institutions. For example, Rebecca Kronman, who attended the Business High School in Washington, D.C., played on several 1920s championship basketball teams; as Betty K. Shapiro, she served as president of B’nai B’rith Women International in the late 1960s. More recently, outstanding basketball player Nancy Lieberman-Cline dominated the women’s college game during her years as an All-American at Old Dominion University in Virginia in the 1970s. Lieberman, a basketball superstar, made the 1980 Olympic squad and played in the women’s professional basketball league in the early 1980s. A few Jewish players competed in the highly competitive National Collegiate Athletic Association women’s basketball tournament in 1995.

Swimming and Additional Sports

Additional sports opportunities existed for some women and girls at Jewish institutions. The YWHA’s new swimming pool in New York opened in 1916 and represented a major part of promoting sport and physical culture for working girls and women. This excellent pool hosted not only recreational classes but also national competitive swimming championships featuring prominent national and Olympic champions such as Aileen Riggin and Gertrude Ederle in the 1920s. Aileen Riggin, 1920 Olympic gold medal diving champion and 1924 diving and swimming champion, recalled how as a member of the Women’s Swimming Association of New York, founded by Charlotte Epstein, the association’s manager who was also the 1920 and 1924 Olympic women’s swimming team manager, she swam at the YWHA pool for a national championship. An outstanding pool regularly used for both health and competitive purposes, one commentator identified it as a key part of the New York 110th Street YWHA, which “has the most comprehensive program of physical education in the country for Jewish women and girls.” Swimming meets focused on maintaining femininity and fitness while competing in athletics in the context of gender expectations. Thus a newspaper article featuring Eugenia Autonof, who won the 100-yard freestyle at the YWHA Aquatic Carnival, referred to her as “A Harlem Mermaid Scores in A Metropolitan Swimming Meet.” I.K.S. Neighbors urged girls to tell their mothers that “This keeps [us] in good form and—here’s a secret—thin also.” Whether or not mothers and daughters alike heeded this advice, the Irene Kaufmann Settlement organized girls’ swimming teams for competition.

Jewish Ys encouraged women and girls to swim to acquire a feminine body while experiencing the excitement of competition. Women achieved victory in competitive swimming: Marilyn Ramenofsky, who broke the world record in 1964 in the 400-meter freestyle, won a silver medal in this event in the 1964 Olympics. Hillary Bergman and Wendy Weinberg of the United States each won medals in swimming events in the 1977 Maccabiah Games.

Furthermore, outdoor sports offered health dividends for working girls generally confined indoors. So around 1920 the YWHA even emphasized baseball, usually a male sport, at the Y’s country house in White Plains, the forerunner to the YWHA’s Ray Hill Camp in Mt. Kisco, New York. Other outdoor sports endorsed by the YWHA and available at various summer camps for young women were tennis, track and field, archery, croquet and outdoor swimming. A wide range of sports for women and girls, from bowling to volleyball, together with Jewish activities, provided health and enjoyment.

Competition

Some women distinguished themselves in public sporting competitions in the early decades of the twentieth century. Track and field star Lillian Copeland earned Olympic medals in the 1928 and 1932 Olympic Games. Copeland was a superb athlete at the University of Southern California, playing several sports. She excelled in track and field and won numerous national titles in the discus throw and shot put in the 1920s and early 1930s, winning the gold medal for the discus throw at the 1932 Olympic Games. Accomplished track athlete Edith Chaiken of Northwestern University won the national championship in the 440-yard dash for girls in 1914.

Female track and field star Sybil Koff contributed to American victories at the 1932 and 1935 Maccabiah Games, winning seven gold medals at these first two Maccabiads. At the age of nineteen, Sybil (Syd) Koff Cooper of New York (1913–1998) was a star at the first Maccabiah in 1932, when she won four events in track—the 100-meter race, the high jump, the broad jump and the women’s triathlon, winning the 100-meter dash in front of twenty-five thousand spectators. In the 1935 games Koff excelled again; she won three first places—in the 60-meter dash, 400-meter hurdle and 200-meter dash—and placed second in the broad jump. In the second Maccabiad the track and field stars Copeland and Koff led the American team to win “the Manischewitz Trophy, symbolic of supremacy in track and field events.” The American Hebrew in 1935 remarked, “Miss Koff, the Maccabiad star, was the leading Jewish girl athlete of the year winning the 200 Metre Metropolitan A.A.U. title.” During their careers, Copeland and Koff competed against the great Mildred “Babe” Didrickson and other world-class athletes. Koff almost earned a place on the 1932 American Olympic track team, narrowly being eliminated in the sprints and hurdles. Qualifying for the track team, she was also a contender for the 1936 Olympics, held in Nazi Germany, but boycotted the games together with other Jewish athletes. In 1940 Koff won the women’s 80-yard hurdles at the National Championships, the qualifying trials for the upcoming Olympic Games, beating American record holder Marie Cottrell; she qualified for the 1940 Olympic Games in Helsinki, but the Games were cancelled.

Tennis was early considered a suitable feminine sport. In August 1928, an article in the American Hebrew featured Clara Greenspan, the captain-coach-manager of the Hunter College tennis team and winner of the Women’s New York State Doubles Championship, Eastern Clay Court Championship and other tournaments. The article hailed Greenspan as fitting the feminine form and described her “fine complexion that comes with a healthy outdoor life,” concluding that she “makes a picture equally attractive on the court or in a ballroom.” To foster tennis participation and female fitness, in the 1920s the National Council of Jewish Women, Junior Auxiliary, sponsored tennis tournaments for girls in New York. In the 1940s, Helene Irene Bernhard earned the number-four ranking in United States singles, one of the highest rankings achieved by an American Jewish woman. Outstanding champions also include Julie Heldman, a national junior champion and winner of the 1969 singles, doubles and mixed doubles in the 1969 Maccabiah Games. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Heldman achieved a number-five world ranking. The success of women in tennis championships has continued with Andrea Leand, a top junior player and winner of the tennis competition in the Maccabiah Games in 1981, who turned professional in the 1980s.

Gender Roles

While some Jewish female athletes gained experience in sport through collegiate and Jewish Y programs, women and girls of the middle and upper ranks participated in more elite sports like tennis and golf at Jewish country clubs. By the 1920s, several Jewish clubs had been founded by wealthy German Jews when antisemitism prohibited Jews from joining Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, elite country clubs. These locales became places for social, recreational, and competitive sports. The American Hebrew printed articles on sports at country clubs and cited the accomplishments of female golf stars, although their gender roles as wife, mother or daughter shaped the descriptions of athletic prowess.

For example, Elaine Rosenthal Reinhart, the best Jewish female golfer in the United States, exhibited great talent on the golf links, winning the Women’s Western Golf Championship for the third time in 1923 However, observers in the American Jewish press tended to comment on her husband’s good golf as well, emphasizing Reinhart’s marriage. “How often Mr. Reinhart was a golf widower is not in the records, but that Mrs. Reinhart lost neither heart nor cunning in the games was again proved” when she was Western Women’s Golf Association champion in 1918. Other golf champions included Mrs. Louis Lengfeld, winner of the Northern California crown in 1927 and member and golf captain of San Francisco’s exclusive Beresford Country Club. Mrs. Harry Grossman, who won the 1929 Women’s Golf Championship of Los Angeles, belonged to the well-known elite Jewish Hillcrest Country Club. Amy Alcott has earned victories and prize money on the Ladies Professional Golf Association tour.

The emergence of Jewish resorts by the sea or in the mountains provided another locale for experiencing a sports culture. Resorts and hotels in a rural atmosphere flourished in the Catskill Mountains. For working- and middle-class Jewish urbanites in Chicago and Detroit, summer vacation spots like South Haven, Michigan, provided sports and recreation.

Through the auspices of several Jewish institutions, women and girls participated in sport and physical education for enhancing health, for taking part in Americanization programs, or for engaging in physical recreation deemed appropriate for females. As sport increasingly played a significant role in American society in the twentieth century, it also became part of Jewish women’s experiences in American life. Through the years, women and girls participated in swimming, basketball, gymnastics, tennis, track or golf in their physical pursuits in American culture.

Addams, Jane. Spirit of Youth and the City Streets (1923), and Twenty Years at Hull-House (1910, 1960).

Bellow, Adam. The Educational Alliance: A Centennial Celebration (1990); Blitzer, Grace Rosenberg. “Junior Jottings—and Golf and Tennis.” The American Hebrew 115 (November 7, 1924): 853.

Educational Alliance Records. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, YIVO Archives, New York; Borish, Linda J. “‘An Interest in Physical Well-Being among the Feminine Membership’: Sporting Activities for Women at Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Associations.” American Jewish History 87 (March 1999).

Cohen, Lou E. “Sport Chats: Syd Koff—She Suddenly Became an Athlete and Rose to Champion.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Aug. 22, 1934.

Cooper, Steve. “The Story of Sybille—True And Complete.” Sybille Gallery Newsletter, Summer 1998:1–2.

Eisen, George. “Sport, Recreation and Gender: Jewish Immigrant Women on Turn-of-the-Century American (1880–1920).” Journal Of Sport History 18 (Spring 1991): 103–120.

Ewen, Elizabeth. Immigrant Women in the Land Of Dollars: Life and Culture on the Lower East Side, 1890–1925 (1985).

Gems, Gerald R. “Sport and the Forging of a Jewish-American Culture: The Chicago Hebrew Institute.” AJH 83 (March 1995): 15–26.

Goodman, Cary. Choosing Sides: Playground and Street Life on the Lower East Side (1979); Gumpert, Bertram Jay. “A Rising Tennis Star.” The American Hebrew 123 (August 3, 1928): 389.

“Highlights on Links and Polo Fields.” The American Hebrew 123 (June 1, 1928): 94+; “Hows and Whys of Big Burg’s Y’s. 110th Street Y.W.H.A. Has Most Comprehensive Physical Education System of Type in Entire Country.” New York Post, January 17, 1936.

Irene Kaufmann Settlement House, Pittsburgh, PA. I.K.S. Neighbors. Vols. 1–5 (1923–1927); “Jewish Sportsmen on Parade.” American Hebrew 136 (June 7, 1935): 94.

Jewish Training School of Chicago. Second Annual Report Of The Executive Board (1890–1891). Chicago Jewish Archives/Spertus Institute, Chicago, IL; “Jewish Who’s Who—1935, Sports.” American Hebrew 138 (Dec. 20, 1935): 193.

Kraus, Bea. “South Haven’s Jewish Resort Era: Its Pioneers, Builders amd Vacationers.” Michigan Jewish History 35 (Winter 1994): 20–25.

Levine, Peter. “The American Hebrew Looks at ‘Our Crowd’: The Jewish Country Club in the 1920s.” AJH 83 (March 1995): 27–49, and Ellis Island to Ebbets Field: Sport and the American Jewish Experience (1992).

“Lillian Copeland, 59, Dies; Won Olympic Medal in 1932.” Nytimes, July 8, 1964, 35:1.

Meites, Hyman L. Ed. History of the Jews of Chicago (1927); “Miss Epstein Dead; Olympics Official.” NYTimes, August 27, 1938, 13:4.

“Miss Koff Scores in Jewish Games.” NYTimes, April 2, 1932:21; “New Home for Girls’ Club.” Nytimes, April 26, 1914.

Peiss, Kathy. Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (1986); Polacheck, Hilda Satt. I Came a Stranger: The Story Of a Hull-House Girl. Edited By Dena J. Polacheck Epstein (1989).

Postal, Bernard, Jesse Silver, And Roy Silver. Encyclopedia of Jews in Sports (1965).

Rabinowitz, Benjamin. The Young Men’s Hebrew Association (1854–1913) (1948).

Riess, Steven A. City Games: The Evolution of American Urban Society and the Rise of Sports (1989), and “Sport and the American Jew: A Second Look.” AJH 83 (March 1995): 1–14.

Rosenberger, Ruth. “Personalities in the World of Golf and Tennis.” The American Hebrew 124 (May 3, 1929): 966+; Seman, Philip L. “The Problem of the Leisure Hour, A Challenge: One Way of Meeting It.” Jewish Peoples’ Institute Annual Report, Chicago (1927).

Slater, Robert. Great Jews In Sports (1983. Rev. Ed. 1992).

Soule, Aileen Riggin. Interview with Author, June 16, 1996. Department of History, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Mich; Spears, Betty. “Senda Berenson Abbott: New Woman, New Sport.” In A Century Of Women’s Basketball: From Frailty To Final Four, Edited by Joan S. Hult and Marianna Trekel (1991).

“Sybil Cooper, 1913–1998.” Archives of the Pierre Gildesgame Maccabi Sports Museum, Kefar Maccabiah, Ramat-Gan, Israel; Sybil Cooper, Track Star, 85.” Forward, May 29, 1998:10.

“Thrice Western Women’s Golf Champion.” The American Hebrew 117 (November 6, 1925): 828); Wald, Lillian D. The House on Henry Street (1915, 1971).

Young Women’s Hebrew Association. Records. 92nd Street Young Men’s-Young Women’s Hebrew Association Archives, New York; Young Women’s Union of Philadelphia. Neighborhood Centre Records. Philadelphia Jewish Archives Center, Balch Institute, Philadelphia, PA.