Honoring the Real First Woman Rabbi

For nearly thirty years I have had the good fortune to carry the title “first woman rabbi ordained in the Conservative Movement.” I have carried the designation with pride, at the same time knowing that I was a relative newcomer to the world of “first women rabbis.” After all, Rabbi Sally Priesand (the first woman Reform rabbi, ordained by the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in 1972) and Rabbi Sandy Sasso (the first woman Reconstructionist rabbi, ordained by the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in 1974) had preceded me by many years. Only this week did I come to know my forbear, Rabbi Regina Jonas, the first woman ever ordained a rabbi.

Regina Jonas, born into a poor Orthodox Jewish family in Berlin in 1902, dreamed of being a rabbi at the astonishing age of 11, far before the Jewish world was ready to support her aspirations. During the 1920s, she studied at the Academy for the Science of Judaism, taking all the same courses and exams required of rabbinical students, and wrote her rabbinic dissertation on the remarkable topic, “Can Women Serve as Rabbis?” The faculty member who seemed ready to ordain her suddenly died and the institution agreed only to grant her the degree of “Academic Teacher of Religion.” But in 1935, she was ordained as a rabbi by Rabbi Max Dienemann, representing the association of liberal (Reform) rabbis in Berlin. At first she was invited to work in schools, Jewish hospitals and nursing homes. As many rabbis fled the country, so that there was more unmet need for rabbis, Rabbi Jonas was able to serve in several synagogues that were desperate for rabbinic leadership as catastrophe approached. Regina Jonas was deported to Terezin in November of 1942, where she worked with psychologist Viktor Frankl in the camp before being deported to Auschwitz on October 12, 1944, where she was murdered.

For decades her name and her story were virtually unknown. When her long-hidden documents became available in the 1990s, rabbis and feminist scholars became fascinated by her story. This week, a group of female rabbis, scholars, and Jewish communal leaders, sponsored by the American Jewish Archives and the Jewish Women’s Archive, traveled to Berlin and to Terezin and Prague to pay homage to Rabbi Regina Jonas, to honor her work on behalf of Jewry and of Jewish women, and to restore her rightful place in Jewish women’s history.

Our journey began in Berlin, where Regina Jonas was born, educated and ordained, and where she served as a rabbi. We visited places where she had lived, perused copies of her archived documents, and tried to imagine what could have moved a young woman to dare to dream of the rabbinate in her time and place. We visited Holocaust sites, including a Jewish neighborhood with banners recalling the Nuremberg laws, the “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe” and the magnificent Jewish museum of Berlin. We met with government officials who expressed genuine anguish about the rise of anti-Semitic attitudes in Germany, especially as war rages in Israel and Gaza. And we had the joy of meeting with rabbinical and cantorial students at the Abraham Geiger College in Berlin, the new generation of leaders working for the miracle of renewed Jewish life in Germany.

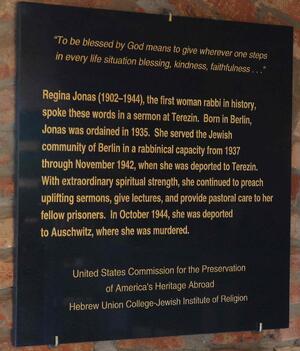

The trip reached its climax in Terezin, where we dedicated a memorial to Rabbi Regina Jonas at the ghetto/concentration camp where she served, taught and suffered. America’s first four women rabbis huddled together over the list of Rabbi Jonas’ lecture notes, trying to imagine how she had found the strength to teach about Shabbat and Jewish holidays and inspire faith and hope in her people in the midst of such darkness. We met with a survivor who, as a teenage artist in the camp, had documented what she had seen and was one of the few children of Terezin who survived to bring her art to the world. We then stood in the solemnly beautiful columbarium hall as the survivor-artist’s son and granddaughter played exquisite, haunting music, evoking the losses of the past and prayerful hopes for the future. The first four American women rabbis honored our foremother by reading passages from her writings, and we recited the “El Malei Rachamim,” “God Who is Full of Compassion,” the prayer for the soul of the departed, that was never recited over this pioneering, visionary woman leader.

Rabbi Regina Jonas’s story had been written out of history twice—once because the Nazis robbed her of life and again because the post-war Jewish community was unready to celebrate her story. But this week our delegation embraced Rabbi Regina Jonas as our foremother, teacher and colleague, pledging to remember her gifts, her vision, and her courage. Zichrona livracha. Her memory is a blessing to us all.

This blog post originally appeared in The Times of Israel