Letty Cottin Pogrebin

The Preview issue of Ms., which hit the newstands in January 1972, speaks volumes about the concerns of Second Wave feminism and the commitments of the magazine's five founding editors, myself among them.

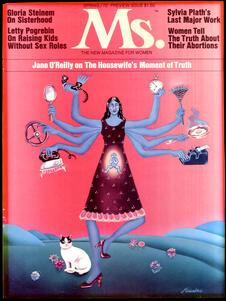

The multi-armed, blue-skinned cover image – we purposely chose an iconic figure to avoid racial favoritism – embodies the burdens and obligations of the female role. Mother, worker, housekeeper, cook, car-pool driver, keeper of the social life, slave to time, seeker of beauty, object of the male gaze, she is weeping because she cannot do it all. She cries because her labor is unseen, taken for granted, unrewarded. She cries because she is dancing as fast as she can and has no energy left for herself. She is Everywoman, and she is exhausted.

Our goal at Ms. was to make such lives visible, to honor women’s work, and to expose the legal, economic, and social barriers that stand in the way of women’s full humanity. Ms. provided a forum where disparate voices – housewives, lesbians, political radicals, cancer survivors, victims of rape, violence, and incest, brave feminist trouble-makers – could be heard on issues that were being ignored by mainstream women’s magazines and papered over by “feminine” propriety in the public square. Ms. showcased women writers and artists. We publicized grass-roots organizations and local feminist leaders. We reported on street demonstrations, consciousness- raising groups, cutting-edge lawsuits, and legislative initiatives. We advocated for the beleaguered and the silenced. We were rabble-rousers. We helped make a revolution.

The cover lines on the Preview issue are illustrative of where we began: Gloria Steinem’s paean to sex pride and sisterhood. The fight to legalize abortion. Sylvia Plath’s luminous fiction. Jane O’Reilly’s epiphanic essay on housework. My piece on sex role stereotyping and how it squelches children’s dreams.

There is no question in my mind that my 20-year involvement in Ms. – like my 35-year commitment to the women’s movement, both secular and Jewish – is rooted in faith and family. I grew up in a home where advancing social justice was as integral to Judaism as lighting Shabbat candles. My parents, both passionate Zionists, were active volunteers in our synagogue and the wider Jewish community. Having learned from them to stand up for my dignity as a Jew, I suppose it was natural for me to stand up for my dignity as a woman, which, after all, is what feminism is all about.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin earned her B.A. from Brandeis University and became a writer and strong advocate for women’s rights in the early 1970s. In 1971, she was one of the founding editors of Ms. magazine, where she worked for 17 years, and a co-founder of the National Women’s Political Caucus. She was also a consultant on Free To Be You And Me, an album of non-sexist children’s stories and songs, and edited Stories for Free Children. When the United Nations International Women’s Decade Conference equated Zionism with Racism in 1975, Pogrebin was provoked to combat anti-Semitism within the women’s movement just as she fought sexism within Judaism. Over the last three decades, Pogrebin has been a fixture in feminist, Jewish, and Jewish-feminist causes, as well as an outspoken political activist on issues including hunger, the Israel-Palestine conflict, and Black-Jewish relations. She is a prolific author whose publications include Getting Yours: How to Make the System Work for the Working Woman; Growing Up Free: Raising Your Child in the 80s; Deborah, Golda, and Me: Being Female and Jewish in America; and Three Daughters.