Letty Cottin Pogrebin

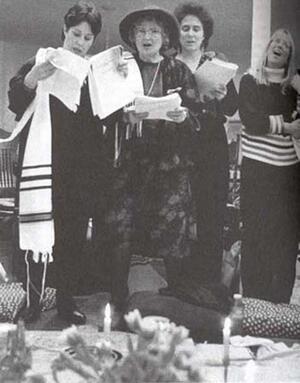

Feminist seders have provided an important context for developing women’s spirituality. In 1975, a group of Israeli and American women decided to create their own Passover seder based on their experiences as Jewish women. Now an annual event held in Manhattan, it has been attended by Esther Broner, Gloria Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Bella Abzug, Grace Paley and several other "Seder Sisters" who have played important roles in the development of Jewish feminism. Shown here are Bella Abzug, Phyllis Chesler and Letty Cottin Pogrebin at the Women's Seder in 1991.

Photo: Joan Roth

Letty Cottin Pogrebin--a writer, activist, editor, organizer, and advocate--gained national recognition first in the national women’s movement and later as a spokesperson for Jewish feminism and issues related to Israel-Palestine. Growing up in a religiously observant Conservative household, Pogrebin became outraged at the exclusion of women from full participation in Jewish ritual and tradition, leaving her determined to create a more inclusive Judaism. In her work, whether fiction or nonfiction, Pogrebin writes colorfully and honestly about her life and its complexities while simultaneously echoing the experiences of millions of women. In fact, Pogrebin’s memoir, Deborah, Golda, and Me, gave a public face to Jewish feminism. Over the years, Pogrebin merged political activism, feminism, strong Jewish identity, and intercultural harmony.

Introduction

Letty Cottin Pogrebin is a liberal Jew and an outspoken advocate for women, families, intergroup dialogue, and Middle East peace. Her significant impact and loyal fan base in the Jewish community have resulted from her articulation of a more egalitarian vision for religious leadership and liturgy and her fierce insistence that Jewish values can guide the Jewish people to a deep, humane Zionism that does not denigrate or ignore another people.

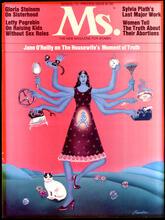

Pogrebin gained national recognition first in the national women’s movement and later as a spokesperson for Jewish feminism and issues related to Israel-Palestine. Primarily a writer, she is also an activist, editor, organizer, and advocate for numerous causes—women’s equality, writers’ rights (she was a founding editor of Ms. Magazine and served two terms as president of the Authors Guild), nonsexist child rearing (her book Growing Up Free was the Dr. Spock for baby boomers), social and economic justice, expansion of women’s role in Judaism, eradication of racism and anti-Semitism, advancement of black/Jewish rapprochement, and Mideast peace.

Family and Education

Born on June 9, 1939, in Manhattan, Letty Cottin grew up in a religiously observant Conservative household in Jamaica, Queens. Her father, Jacob Cottin, a lawyer, was a leader in the Queens Jewish community, County Commander of the Jewish War Veterans, and President of the Jamaica Jewish Center, the family’s synagogue. Her mother, Cyral (Halpern) Cottin, an amateur painter and former dress designer, was an active member of the synagogue Sisterhood, Hadassah, the National Council of Jewish Women, Na’amat, and WIZO.

Pogrebin was Jewishly educated at the Yeshiva of Central Queens and Jamaica Jewish Center Hebrew High School. In 1952, she became one of the first girls in Conservative Judaism to become a bat mitzvah. In 1959, before turning twenty, she graduated from Brandeis University, earning a B.A. cum laude with distinction in English and American literature. She married Bertrand B. Pogrebin, a labor and employment lawyer, in 1963.

Pogrebin’s outrage at the exclusion of women from full participation in Jewish ritual and tradition was sparked when her mother died in 1955 and Pogrebin, age fifteen, was not permitted to count in the Lit. (Aramaic) "holy." Doxology, mostly in Aramaic, recited at the close of sections of the prayer service. The mourner's Kaddish is recited at prescribed times by one who has lost an immediate family member. The prayer traditionally requires the presence of ten adult males.Kaddish The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyan. Deeply pained, she turned her back on organized Judaism for fifteen years, refusing to affiliate with any shul or Jewish organization. She did, however, continue to observe many Jewish traditions at home, lighting Shabbat candles and hosting elaborate holiday meals and Hanukkah festivities with her family—husband, Bert, twin daughters Robin and Abigail (b. 1965), and son David (b. 1968)–plus assorted relatives and friends. As Pogrebin comments in her bestselling memoir, Deborah, Golda, and Me, “Rebellion was one thing; giving up the Jewish holidays was something else. I wasn’t going to let my alienation from my father’s religious institutions cut me off from the rituals [I] associated with my mother and the home-based Judaism in which my heritage felt ... most real.”

Multi-Faceted Writings

Pogrebin has written colorfully and honestly about her own life, intensely focusing on the complexities of each phase as she lived it, while mirroring the aspirations, frustrations, dislocations, and transformations experienced by millions of women of her generation. Having been ahead of the wave on so many issues, she also speaks to the concerns of younger women and grapples with matters of consequence to all women: discrimination in the workplace (the subject of her books How to Make It in a Man’s World and Getting Yours: How to Make the System Work for the Working Woman), the challenges of parenthood (Growing Up Free, a guide to raising children without sex-role stereotypes), the vicissitudes of friendship (Among Friends), the interface between power relations in the home and public sphere (Family Politics: Love and Power on an Intimate Frontier), the truth about aging (Getting Over Getting Older), and help guiding others through illness and loss (How to Be A Friend to A Friend Who’s Sick).

Jewish themes–identity, continuity, superstition, loyalty to family, friends, and the Jewish story–play prominent roles in both of Pogrebin’s published novels. Three Daughters describes the enduring trauma caused by a family secret that roils the lives of three sisters and their father, a charismatic rabbi. In Single Jewish Male Seeking Soul Mate, the son of Holocaust survivors promises his mother on her deathbed that he will marry a Jew and raise Jewish children, only to fall in love with a militant African-American talk show host who is a believing Baptist.

In her analytical nonfiction books, Pogrebin draws upon personal anecdotes to introduce and buttress her position on a variety of issues, such as love, work, faith, sex, motherhood, family, feminism, and politics. The intimacy she fosters with her readers and lecture audiences clearly derives from her own comfort with self-disclosure. Her classic memoir, Deborah, Golda, and Me, opens with her childhood in an Ashkenazi Jewish home before widening its focus to expound on the condition of “being female and Jewish in America.” This is the book that gave a public face to Jewish feminism, rendering the movement less parochial in the eyes of many who might have been self-conscious about their own identification as Jews. Because of her high visibility—as an outspoken advocate and feminist organizer, and due to her longtime identification with Ms. magazine (her name as a “founding editor” has appeared on the masthead since 1971)—Pogrebin’s chronicling of her encounters with religious and communal sexism and her determination to remain attached to a more inclusive (yet recognizably Conservative) Judaism have drawn audiences of Jewish women all across the country who, having been similarly mistreated or disaffected. They have welcomed her frank critiques with gratitude and similar stories of their own.

Jewish Feminism

For Jewish women trying to incorporate their Judaism into their feminism, or vice versa, Deborah, Golda, and Me has been a landmark book, illuminating a contemporary Jewish woman’s life as almost no other nonfiction work had done. Letty Cottin Pogrebin became the voice most strongly identified with both secular Jewish women’s concerns and the struggle for gender parity in Judaism, its rites, rituals, and communal institutions. She has addressed subjects that have shamed or troubled many thoughtful Jews: patriarchal traditions, antisemitism on the right and left, tensions between Blacks and Jews, the hundred year Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Her advocacy, whether expressed in her writing, speaking, or activism, has always been motivated by clear goals: dignity, equality and inclusion for women and other out-groups, mutual understanding among different constituencies, and meaningful social and institutional change in all spheres of American life.

Over the years, the merger of Pogrebin’s political activism, feminism, and strong Jewish identity has been evident in her involvement with such organizations as the Jewish Fund for Justice, New Israel Fund, UJA Federation Task Force on Women, American Jewish Congress Commission on Women’s Equality, Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, Mazon: A Jewish Response to Hunger, Harvard Divinity School’s Women and Religion Program, and Brandeis University’s Women’s and Gender Studies Program.

In addition to being a strong supporter of the Israeli civil rights movement, Pogrebin was a founder of the International Center for Peace in the Middle East and since 1985 has been a board member of Americans for Peace Now, which she chaired for four years in the 1990s. In 2019, she joined the Advisory Board of Combatants for Peace, an organization of former IDF officers and Palestinian militants who are now committed to the nonviolent resolution of the conflict.

Working for Inter-Group Harmony

Letty Cottin Pogrebin’s four decades of devotion to advancing inter-group harmony inspired her to co-found several Black-Jewish dialogue groups and Jewish-Palestinian dialogue groups, one of which celebrated its twelfth year in 2020. In the secular world, she was a co-founder of the National Women’s Political Caucus; the Ms. Foundation for Women; the Ms. Foundation for Education and Communication; and the Free To Be Foundation, the latter two boards on which she still serves. Among her dozens of honors are a Yale University Poynter Fellowship in Journalism; an Emmy Award for Free to Be You and Me, and inclusion in Who’s Who in America.

But it is in her personal mode, either telling a story about her children and six grandchildren, or “confessing” an aspect of her own spiritual search, that Pogrebin is at her most memorable. She is the feminist who wasn’t afraid to say she “adores” her husband, the liberated woman who stitched a needlepoint pillow with the addresses of all the houses they’d lived in together, the mother who expressed the worries of her ideological sisters about how to balance family, work, and movement activities (she seems to have given her own offspring tenderness and independence), the feminist who counts among her friends literary lions, actors, senators, and heads of state, yet still cares about making crisp potato latkes and setting a beautiful seder table.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin has a voice that is both strong and sweet. Her place in our Pantheon is guaranteed by the fact that hardly any Jewish feminist event feels complete without her presence.

Selected Works

Single Jewish Male Seeking Soul Mate: a novel. New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2015.

How to Be a Friend to a Friend Who’s Sick. New York: PublicAffairs, 2013).

Three Daughters. New York: Penguin, 2003.

Free to Be...A Family (consulting ed.), 1998.

Getting Over Getting Older: An Intimate Journey. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1996.

Deborah, Golda, and Me: Being Female and Jewish in America. New York: Crown Publishers, 1991.

Among Friends: Who We Like, Why We Like Them, and What We Do with Them. New York: McGraw Hill, 1986.

Family Politics: Love and Power on an Intimate Frontier. New York: McGraw Hill,1983.

Stories for Free Children (ed.). New York: Bantam, 1983.

Growing Up Free: Raising Your Child in the ’80s. New York: Bantam, 1980.

Getting Yours: How to Make the System Work for the Working Woman. New York: Avon, 1975.

Free to Be...You and Me (consulting ed.), 1974.

How to Make It in a Man’s World. New York: Bantam, 1970.