Yiddish Theater in the United States

Women have always been important as both Yiddish theater audiences and actors. The Golubok company, with star Madame Sara Krantsfeld, was the first to arrive in the United States, in 1882, at the start of the great wave of Jewish immigration. For a decade and more, most American Yiddish actors were immigrants, as were their audiences. Many female actors married men in the theater community and their names have remained linked in pairs with their husbands’. Often families played in the same company, such as the famous Adler family. Women were also connected with professional Yiddish theater in creative capacities other than performing, including composition, playwriting, and scholarly work. Now, as Yiddish theater has become attenuated, the loyalties and memories of women are important for its survival.

During the Middle Ages and for most of the centuries since then, Ashkenazim—the Yiddish-speaking Jews of central and Eastern Europe—produced virtually no theater at all. Since ancient times, rabbinic Jewish tradition had disapproved of theater, for men and women alike. Moreover, it was specifically considered immodest for women to perform for men. Men were prohibited from hearing women’s voices singing, and women were prohibited from dressing as men. Finally, unlike other Western cultures, in many of whose theaters men played women’s roles up into early modern times, Jewish men were permitted to dress as women only as part of the topsy-turvy merrymaking of the Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim holiday. For that reason, it was only during Purim, in early spring, that lively amateur entertainments were produced, and even then women participated only as spectators. Professional Yiddish theater did not exist until 1876. Until then there were only groups of wandering acrobats, among whom, however, two women’s names are recorded: Ruza and Feygele.

Nineteenth-Century Yiddish Theater

During the late-nineteenth-century Jewish Enlightenment; European movement during the 1770sHaskalah [Enlightenment] period, when Eastern European Ashkenazi culture was becoming more modern and cosmopolitan, some Yiddish plays were written to be read at home as sophisticated literary entertainment. The first recorded actual performance of one of these plays was organized in 1862 by Madame Slonimsky, wife of the new headmaster of the Zhitomer Academy for boys in Zhitomer, Poland. Her husband’s students played all the roles. The play was Serkele, by Shlomo Etenger. The title role, a strong-willed female character, was played by a boy named Avrom [Abraham] Goldfaden, who grew up to establish the first professional Yiddish troupe.

Goldfaden’s troupe, formed in Jassy, Romania, in 1876, was one manifestation of a general loosening of governmental restrictions on Jewish culture from the outside, as well as a loosening of traditional rabbinic restrictions from inside. The first company consisted of Goldfaden plus one actor. He soon hired a second actor, Sakher Goldstein, to play women’s roles as well as men’s. Goldfaden’s wife, Paulina, served the enterprise as the translator of French and German popular plays into Yiddish.

Probably the first woman to perform on the Yiddish stage was Sara Segal, a sixteen-year-old seamstress with dark eyes and a sweet soprano voice. However, her mother refused permission until Goldstein, being the only unmarried company member, married her and took her along on their wandering life. She changed her name to the European-sounding Sophie, becoming Sophie Goldstein. Later, in New York, she married another actor, making her name Sophie Goldstein-Karp, or Sophia Karp. Karp was the first woman whose profession was Yiddish theater, and she was typical of the many hundreds who followed. She was an actor, known for glamour and charm. She occasionally participated in a venture as producer or even director as well as star. (Karp is said to have died of a theatrical dispute. In an effort to prove her claim on a certain theater, she refused to leave the building, even sleeping on the unheated stage, until she caught pneumonia and died.) But this was minor, and in fact women in Yiddish theater were primarily performers.

The Golubok company was the first to arrive in the United States, in 1882, at the start of the great wave of Jewish immigration. Their prima donna was a Madame Sara Krantsfeld. Sophie Karp and many other actors came shortly afterward. For a decade and more, most American Yiddish actors were immigrants, as were their audiences, but Yiddish theater was so new that many who were born in Europe made their debuts in the new land. Others started careers in the Old Country and then immigrated; by 1900, talent scouts were aggressively importing actors whose reputations had arrived at Ellis Island along with other news from home.

Most of the qualities associated with Yiddish actors were already clear in the 1880s. Theatergoers favored fiery temperament and emotionalism in drama, and “quicksilver” energy in comedy, for female and male actors alike. As the theater acquired serious playwrights and discriminating audiences, truthfulness and sensitivity became highly valued. Types, in the styles of the period, included queenly lovers, strong heroines, glamorous villainesses, saucy soubrettes, and devoted mammas. And since music was interpolated in most shows, even including serious straight dramas, a good singing voice was also important.

From the beginning, many female actors married men in the theater community, and their names were and have remained linked in pairs with their husbands’. Eventually there came to be many actors’ daughters as well. Often families played in the same company. Companies generally formed for a season, or for a tour, and touring companies moved not only around the United States but also back and forth to Eastern Europe and Russia. It was also not unusual to visit Western Europe, South America, or South Africa. On tour many actors took along their children, who soon learned to perform. The American capital of Yiddish theater was New York City, where at times as many as fourteen theaters were filled simultaneously, not counting vaudeville and cabaret. But there were also professional theaters in other cities around the country, such as Philadelphia, Detroit, and Providence.

Because the Yiddish public was passionate about theater, they generally were aware of actors’ private lives, including romances, which were matters of comment in theater columns and critiques in the press. Although respectable families were not pleased if their daughters went on the stage, actors committed to intellectual or political ideals were highly respected by the intelligentsia, and for the community at large the presence of actors lent dash and style to café life. Actors, like other performers, customarily contracted for one night a season to be played for their own benefit. In this practice, not unique to Yiddish theater, the performer picked and cast the play. On these benefit nights, the house might be filled with an actor’s enthusiastic fans, and the box office take came to a significant yearly bonus. She might also receive gifts in addition to money profits.

Popular Stars of the Yiddish Stage

In this early period began the long career of Bina Abramovich, who fifty years later was still known affectionately as the “mother” of Yiddish theater, both because she had always been there and because the roles she was associated with were folksy Old Country mammas. Pretty, lively Dina Stettin played with her husband Jacob Adler in London en route to America, and finished her career there married to Seymour Feinman, after which she became known as Dina Feinman. Regina Prager was known for her operatic singing and dignified carriage.

Bessie Thomashefsky met her husband, Boris, when she was a girl in Baltimore and he came there to start a Yiddish theater. Through her long, successful career, she played many roles, both comic and deeply dramatic, light and intense. She even played mischievous little boys. Her many enthusiastic fans extolled her acting as “natural,” a term of particularly high praise.

Starting in 1890, some actors were known not only for their work in popular theater but also in association with the playwright Jacob Gordin, whose literary repertory dominated the more intellectually ambitious Yiddish theater between roughly 1890 and 1905. Among Gordin’s political causes was women’s rights, and among his dramatic talents was writing juicy roles, often with certain stars in mind. Gordin was the first, though certainly not the last, professional Yiddish dramatist to create thoughtful and intelligent female characters. Keni Liptzin, Bertha Kalich, and Sara Adler remained permanently associated with Gordin roles.

Keni or Kenia Liptzin ran away from home to join one of Goldfaden’s earliest troupes and played in many companies in Eastern Europe and London before she settled in New York and encountered Gordin. Tiny and elegant, she was known for her uncompromising high standards for Yiddish literary repertoire. She was able to play only those plays she respected because she was married to a successful publisher, making her perhaps the only Yiddish theater producer ever who could be financially independent of whether or not her vehicles sold tickets. The role she was best known for was Gordin’s Mirele Efros; or, The Jewish Queen Lear. This tells the story of a woman who loses everything to a scheming daughter-in-law and to her own pride. When the Polish Yiddish star Esther Rachel Kaminska toured in New York in that same role, the Yiddish press called it a duel of rival champions.

Bertha Kalich began as a chorus lovely in Lemberg, Poland, and though she also played on the non-

Yiddish Polish stage, talent scouts soon brought her to America. She was known for her grace and femininity. Gordin is supposed to have written his popular play of thwarted love, The Kreutzer Sonata, because once, as he sat in her dressing room, she flirted with him, brushing her long dark hair and coaxing, “Write a play for my hair.” She subsequently played the role in English translation on Broadway. She also created the female lead in his Sappho, a photographer who dares to bear a child out of wedlock because the father turns out to be unworthy, and in God, Man, and Devil, an unhappy wife. She played for many years in Yiddish and English even after she became totally blind.

For Sara Adler, Gordin wrote Without a Home. Adler, who began her career as Sara Heine-Haimovitch, rose to fame while married to Jacob Adler. Her fiery temperament delighted her many fans, onstage and off, and she remained a star—possibly the most successful of her generation—for many years. Her daughters Frances, Julia, and Stella Adler all became actors; Stella soon transferred to the English-language stage, where she was an influential performer and teacher.

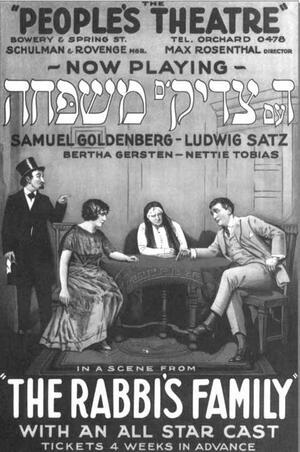

Yiddish theater participated in the art theater movement in the United States, as well as in Western Europe and Russia. In 1917, New York acquired the Yiddish Art Theater, organized by Maurice Schwartz, and the following year the Jewish Art Theater organized by Jacob Ben-Ami. There were others in the New York area and elsewhere. Several actors were associated with this movement, which emphasized text, direction, and ensemble work as opposed to the star system. Celia Adler, raised in traditional Yiddish theater and known for her delicacy and vulnerability, was an enthusiastic reformer, later recalling the period as a “golden era.” So was the glamorous Berta Gersten.

The popular theater in the first half of the twentieth century had many skilled and energetic female performers in a variety of styles. The following are some of the best known. Nellie Casman sang and recorded songs, some of which (like “Yosl”) she wrote herself. Jennie Goldstein starred in tearjerkers and later turned to comedies. Henrietta Jacobson and Yetta Zwerling were popular comedians. Anna Appel and Malvina Lobel were known in dramas. Vera Rosanka billed herself as the Jewish Gypsy. Clara Young was a frilly coquette. Molly Picon, whose mother sewed costumes backstage, began in English-language vaudeville. Her husband, Jacob Kalich, groomed her for stardom—even tutoring her in Yiddish—and helped make her the darling of Yiddish musical theater, cabaret, and films. She was especially popular in gamin roles, even boy roles such as Yankl, the mischievous yeshiva student. Picon ended her career back on the English-language stage, playing in American musical comedies.

Yiddish Theater in the Later Twentieth Century

By mid-century, new names drew audiences to the theaters. Mina Bern played kleynkunst, charming musical revues that included art songs and scenes of literary value, with her husband, Ben Bonus. Clever Reizl Bozyk, who was actually born onstage on her mother’s benefit night, performed with her husband, Max, and alone, and in old age was highly praised for her role in the Hollywood film Crossing Delancey written by Susan Sandler. Dina Halpern acted and also gave solo literary performances known as “word concerts.” Betty and Jacob Jacobs were a perennial song-and-dance duo. Miriam Kressyn played Yiddish dramas and musicals and in films. Shifra Lerer, trained in Argentinean theater, acted with her husband, Ben Zion Vitler, and appeared in Yiddish films. Lillian Lux, with her husband, Pesach Burstein, and son, Mike Burstyn, had her biggest international success in The Megile of Itsik Manger.

A number of these actors also appeared in one or more of the Yiddish films made in the United States, though film acting was generally less respected than stage productions. Some are better remembered for their film work than from stage appearances: Helen Beverly, Judith Abarbanel, Gertrude Bullman, Lucy Gehrman, Lila Lee, Lucy Levine, Miriam Riselle, Mae Simon, and Florence Weiss. Yiddish radio programs were widespread and popular; Esther Field was a prominent personality. With her husband, Seymour Rechzeit, Miriam Kressyn presented a long-running series of radio shows evoking the history of the Yiddish theater.

There was another venue for Yiddish performance: the resorts of the Catskills. The most famous was Grossinger’s, run by the hotel keeper Jennie Grossinger. Here Yiddish performers did their routines in a mixture of Yiddish and English for increasingly assimilated audiences. There were also opportunities to perform at summer camps like Nit Gedayget.

By the 1970s and 1980s there were a number of new women on the professional Yiddish stage in America. Ida Kaminska, the intelligent and dignified daughter of Esther Rachel Kaminska, spent some years heading her own company here between the time she left Poland and settled permanently in Israel. Just as she performed alongside her famous mother, so her daughter Ruth Kaminska in turn performed alongside her.

Mary Soreanu, born in Romania and based in Israel, spent a number of seasons in New York starring in light musical vehicles designed to show off her strong voice, easy good humor, and good looks. Rita Karen Karpinovitch, trained in the Moscow Art Theater, gave “word concerts.” Vivacious American-born Eleanor Reissa understudied Soreanu early in her career but went on to star in Yiddish, English, and bilingual shows, and to choreograph them as well. Besides her stage appearances here, dark-voiced Raquel Yossiffon has taught university courses about Yiddish theater in Israel. Other young performers of the 1980s and 1990s included Joanne Borts, Adrienne Cooper, Shira Flam, Rosalie Gerut, Ibi Kaufman, and Suzanne Toren.

Amateur theater groups have always been active in Yiddish cultural communities, encouraging new dramatists and providing social cohesiveness. Many were associated with political or social positions, and many provided a congenial venue for artistically ambitious Yiddish dramas. Chayele Ash and Dina Halpern were professional actors who organized and sustained such groups. But there were many unknown heroic women who gave enormous time and energy to organize and sustain these theaters. At the moment, the major established Yiddish theater company in the United States is the Folksbiene, in New York City. The oldest continuously performing Yiddish theater company in the world, the Folksbiene was amateur through most of its years, though it now employs professional artists as well, among whom was Zypora Spaisman (1916–2002), who for fifty years produced and acted in forty-three consecutive productions at the theater.

Female Professionals in Yiddish Theater

Women in professional Yiddish theater have been almost exclusively performers. In the early period, when male stars often headed their own companies, it was rare for women to do so. Keni Liptzin was a major exception, but she was subsidized by her husband; Bessie Thomashefsky, Sara Adler, and Jennie Goldstein were also intermittently company heads, as was Ida Kaminska. Playwrights and songwriters created vehicles for the well-known female performers, but although Molly Picon wrote songs, women rarely wrote their own material; there were no professional women writers or directors. Rose Pivar worked in the Hebrew Actors Union administrative office, and other women were active in the Hebrew Actors Guild. More recently, Renee Solomon served as musical director and piano accompanist for many productions, and Ruth Vool handled theater business as well as performing. Bessie White translated several volumes of Yiddish short plays. Celia Adler and Bessie Thomashefsky wrote their memoirs.

There are women connected with professional Yiddish theater in creative capacities other than performing. Miriam Hoffman has created several plays. The best known are Songs of Paradise, with co-writer Rena Berkowicz Borow and composer Rosalie Gerut, and A Rendezvous with God, about the poet Itsik Manger. Hoffman is the executive director of the Joseph Papp Jewish Theater and teaches Yiddish language at Columbia University. Miriam Kressyn adapted a number of classics for contemporary productions and wrote lyrics for them. Bryna Wasserman Turetsky adapted Mirele Efros for productions at the Folksbiene and the Saidye Bronfman Centre in Montreal. Rina Elisha and Bryna Wasserman Turetsky directed Folksbiene productions. Eleanor Reissa won a Tony for choreographing the bilingual Those Were the Days. Joan Micklin Silver produced the Hollywood feature films Crossing Delancey and Hester Street; the latter, based on the Yiddish story Yekl, incorporated a great deal of Yiddish dialogue. Tova Ronni, of the Folksbiene’s board, organized the installation of devices for simultaneous translation—an innovation that has helped the Folksbiene continue to draw audiences. The United States has also seen numerous tours by the Yiddish Theatre of the Saidye Bronfman Centre of Montreal, founded and directed by Dora Wasserman, who when she suffered a stroke was succeeded by her daughter Bryna Turetsky.

Women have also been active historians of the Yiddish theater. Diane Cypkin, besides performing in Yiddish theater, was curator of the Yiddish theater collection of the Museum of the City of New York. Sharon Pucker Rivo is executive director of the National Center for Jewish Film, which has rescued, preserved, and made available to viewers more Yiddish films than any other institution. Faina Burko has written a major study of the Moscow Yiddish Art Theater, and Edna Nahshon has chronicled the left-wing avant-garde theater ARTEF. Nahma Sandrow translates Yiddish plays, and created several original shows out of Yiddish theater material. Lulla Rosenfeld wrote a biography of her grandfather, Jacob Adler. Evelyn Torton Beck wrote about the influence of Yiddish theater on Franz Kafka’s work. The scholar Ruth Wisse taught a course in Yiddish theater at Harvard University.

Conclusion

Women have always been important as Yiddish theater audiences. In the early sweatshop days, working girls spent hard-earned pennies for tickets. Girls went to the theater in friendly groups or on dates. It was the custom for fraternal organizations to buy out a performance and sell tickets to raise money, and women often went to such performances in order to meet people from back home in the Old Country. Mothers could bring along their children, with picnic lunches to keep them fed during long matinees. Dramas of life in America provided them with ways to learn about the new country and try out, vicariously, new ways to cope. Translations of world classics or of Broadway hits were glimpses of the outside world. Escapist operettas and comedies offered relief from the hardships of immigration and poverty. And women’s tastes influenced the theater world. Actors whom women found handsome played leading roles; there are many tales of women swooning in the aisles and running after Adler or Thomashefsky. Actors whom women admired, whose styles they copied, became stars and remained stars long past their youth. Now, as Yiddish theater is attenuated, the loyalties and memories of women are important for its survival.

For a detailed overview of Yiddish theater see Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater, by Nahma Sandrow (1977). The volume includes an extensive bibliography of sources in both Yiddish and English.