Celia Adler

Celia Adler won acclaim in the Yiddish theater world as a founding member of the Jewish Art Theater. Born to a family of Yiddish actors, Adler was acting by age four. In 1918, she joined Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theater. In 1919, Adler, Jacob Ben Ami, and others left to found the Jewish Art Theater. Their troupe was hailed by Theatre Magazine as the high point of Yiddish theater. Adler continued to perform both serious and melodramatic roles on stage and screen. After World War II, she entertained American troops in Yiddish and English. At age 57, she performed in A Flag is Born with Marlon Brando, a play scheduled for a month that instead ran for thirty weeks. Her last film was Naked City, in 1948.

Celia Adler’s popularity as a Yiddish actor made her a force in the Yiddish art theater movement, where she succeeded despite her lack of a powerful male protector. She was acclaimed for her ability to combine pathos and charm, and those who witnessed her performances especially remember her talent for comedy.

Early Life

Celia Adler’s life was shadowed by her parents’ divorce and the resulting feud that spilled over into the entire New York Yiddish theater world. She was born in New York on December 6, 1889, to Dina Shtettin Adler, who had left her Orthodox home to join the theater and who became the second wife of Jacob P. Adler, foremost actor of the Yiddish stage. Dina Shtettin Adler divorced her husband when he eloped with Sara Heine two years later. Celia was raised by her mother and stepfather, the actor Siegmund Feinman. In need of work, “Madame Dina” continued to appear with Jacob Adler’s troupe and brought her infant onstage as a prop at six months of age. At age four, Celia Adler played a role in Der Yidisher Kenig Lear [The Jewish King Lear], especially written for her by Jacob Gordin.

Educated in New York public schools, Adler originally planned to become a teacher. But after Bertha Kalich praised her performance in Sudermann’s Heimat, she resumed her acting career as Celia Feinman in 1909. She and her mother played in London’s Pavilion Theatre, and in 1910, they toured Poland together.

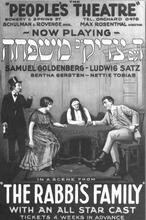

That year, there were at least five Yiddish theaters operating in New York City: the Thalia, the New York People’s Theater, the Liptzin, the Lyric, and the Liberty. When Boris Thomashefsky offered her a contract as understudy for his New York People’s Theater, she signed on as Celia Adler. Years later she recalled in her autobiography the years she went from one temporary contract to another because of the difficulty actors faced in a male-dominated theater world.

Performance Career

Adler’s big break came when she was selected to tour with Rudolph Schildkraut in Shomer’s Eikele Mazik. Subsequently, she played several seasons with Anschel Shur at the Arch Street Theater in Philadelphia, and returned to New York at David Kessler’s invitation to play the Second Avenue Theatre. In 1918, Maurice Schwartz hired her for his Yiddish Art Theater. Others in the troupe included Jacob Ben-Ami, Ludwig Satz, Berta Gersten, and Lazar Freed, whom she married. The couple later divorced. Schwartz was putting on as many as thirty-five plays per season, with actors ad-libbing their way through sketchy plots, aided by the prompter. Adler was usually cast as a weeping maiden or desperate mother. Then, Adler and Ben-Ami persuaded Schwartz to stage a serious drama. The resulting performance, Peretz Hirschbein’s Farvorfen Vinkel [Forsaken Nook], became a hit and was hailed by critics as “the foundation stone of the Yiddish art theater in America.”

After this success, however, Schwartz returned to his former repertory and acting style. Under the leadership of Ben-Ami, a group of actors, including Celia Adler, broke away, founding the Jewish Art Theater (Naye Teater) in 1919. Inspired by the Moscow Art Theater and the new trend to realism in drama, they developed a small literary repertoire with fully realized characterizations. They adopted a single Yiddish dialect to be used consistently and appointed a literary-artistic committee to choose the repertoire. They hired a professional director, Emanuel Reicher of the Deutsche Freie Buehne [German free stage], and engaged professionals to design the sets and lighting. The new theater’s first season—including Hirschbein’s The Idle Inn and Leo Tolstoy’s Power of Darkness—was well reviewed in the New York Times. Theatre Magazine hailed the Jewish Art Theater as the high point in the development of Yiddish theater. But the troupe could not weather a disagreement with its financial backer. Reicher left to become director for the Theatre Guild, and Ben-Ami left for Broadway.

In the 1921–1922 season, Celia Adler, Ben-Ami, and Satz performed at the Irving Place Theater, and the following year Adler acted again under the direction of Maurice Schwartz, appearing as leading lady of the troupe. The 1923–1924 season found her appearing as guest star with Anschel Shur in Philadelphia and touring Europe and America with her brother-in-law Satz. In 1927–1928, Adler tried directing her own repertory company, varying this work with guest roles at the various Yiddish theaters in New York and Philadelphia. While at the Yiddish Art Theater in 1929–1930 at Philadelphia’s Arch Street Theater, she encountered Jack Cone, an actor and theater manager she had known in childhood. As she relates it in her autobiography, she was about to decline an invitation to perform in Buenos Aires because of her fear of traveling there alone, when Cone suggested they marry so that he could accompany her. The couple joined those “vagabond stars” who traveled throughout South America playing cities, out-of-the-way towns, and agricultural colonies. At that time, Buenos Aires boasted five professional Jewish theaters.

Later Life and Career

Adler appeared in two films: Abe’s Imported Wife and the 1937 production Vu Iz Mayn Kind? [Where Is My Child?], a reprise of the melodramatic tearjerkers of her earlier years. In 1938 she joined the Yiddish Dramatic Players, together with the new star of the Yiddish stage, Joseph Buloff.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Yiddish-language theater played out the dramatic transition from Old Country to new and the traumatic process of immigrant adjustment. Out of the emotional turmoil of the flight from Europe, trans-Atlantic migration, and translation to new world poverty, there arose the inventive, re-creative power of Yiddish theater. Through its medium, Jewish immigrants were able to reimagine their previous lives, their present poverty, and their dreams of a better life. But as the immigrants improved their economic status and moved away from the old centers of Jewish life, the troupes lost their earlier base of support in the Jewish neighborhoods. Inevitably, they broke up for lack of funds. While art theaters always have financial problems, the Yiddish art theaters suffered as well from the dispersal of their audience and the decrease in the number of Yiddish-speaking people. Adler made her loyalties clear.

When she accepted a contract to appear in an English-language production of David Pinski’s The Treasure at the Garrick Theater in New York, she wrote a letter to her fans via the Yiddish World explaining that her departure was temporary and promising to return to the Yiddish stage. Spanning the immigrant and “Yankee” generations, Adler was in the rear guard of Yiddish theater.

In the aftermath of World War II, Adler was contracted by the Jewish Welfare Board to entertain troops in American military camps. She presented a program of English and Yiddish songs, and later continued these concert appearances for civilian audiences off-Broadway. But Yiddish theater was dead by that time, not only in the United States but in Russia and Poland as well, where it was literally killed off by communist regimes. At age fifty-seven, Adler was called back to the stage by Ben Hecht, who cast her opposite Paul Muni (an old friend from Yiddish theater days) in his English-language play A Flag Is Born. Members of the cast included Marlon Brando, Quentin Reynolds, and Luther Adler. Scheduled to run four weeks, the play actually went thirty weeks. Later, Adler played a part in the film Naked City (1948). After that contract, she writes, she was happy to sit back and enjoy her career as Bobe Tsili to her grandchildren, daughters of “my son the doctor” Selwyn (Zelig) Freed.

At the time of her death on January 31, 1979, Adler was married to Nathan Forman.

Adler, Celia. Tsili Adler Dertseylt (1959).

AJYB 24:113.

EJ.

EJ necrology (1973–1982).

Lifson, David S. The Yiddish Theatre in America (1965).

Rosenfeld, Lulla Adler. The Yiddish Theatre and Jacob P. Adler (1988).

Sandrow, Nahma. Vagabond Stars (1977).

UJE.

WWIAJ (1938).

Zylbercweig, Zalmen. Leksikon fun Yidishn Teater (1931).