Women's League for Conservative Judaism

Mathilde Schechter.

Courtesy of CJ: Voices of Conservative/Masorti Judaism.

Women’s League for Conservative Judaism (WLCJ,) founded by Mathilde Schechter in 1918 as the National Women’s League of the United Synagogue, is the national organization of Conservative women. Envisioned as the coordinating body of Conservative synagogue sisterhoods, over one hundred years later Women’s League continues to fulfill Schechter’s original vision as an organization whose mission is the perpetuation of Conservative/Masorti Judaism in America through the home, synagogue, and community. Through its programs, publications, classes, and affiliated sisterhoods, it links women with one another, providing mutually supportive community that promotes social connection, wellness, religious commitment, and spiritual wellbeing. Women’s League nurtures “the role women play as keepers of the flames of mitzvot, family, study, Israel, Torah, and community” and empowers women by expanding leadership skills and opportunities.

Introduction

Women’s League for Conservative Judaism is the national organization of Conservative sisterhoods established by Mathilde Schechter in 1918 as the National Women’s League of the United Synagogue. Schechter continued the work begun by her husband, Solomon Schechter, who had called for women to assume a role in the newly established United Synagogue of America, now known as the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ.) As founding president (1918–1919), she envisioned an organization that would be the coordinating body of Conservative synagogue sisterhoods and inspired Women’s League to promote an agenda whose mission was the perpetuation of traditional Judaism in America through the home, synagogue, and community. The early leaders disseminated their message through the publication of educational materials in English, which helped young women through the process of acculturation and Americanization. One of Schechter’s first projects adopted by Women’s League was the opening of a students’ house offering Jewish students in New York a homelike atmosphere with room and kosher board. After succeeding in New York, the project was expanded to other cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, Denver, and Detroit.

By 1925, Women’s League had grown from the founding 100 women in 26 sisterhoods to a membership of 20,000 in 230 sisterhoods in six branches in the United States and Canada. In 1939, six additional branches were added, and membership had multiplied five-fold. By 1968, WLCJ reached a peak of 200,000 members affiliated with 800 sisterhoods in 28 branches. After a consolidation resulting from changing demographics, Women’s League in 1997 had 150,000 members affiliated with 700 sisterhoods in 25 branches. In 2008, Women’s League reorganized, replacing its branches with thirteen regions in the United States and Canada. Reflecting the shrinking demographics of the Conservative Movement, membership in 2021 stands at 40,000 members in some 350 sisterhoods, with the term “affiliates” now preferred over “sisterhoods.” Membership is also available to individuals who are not affiliated with a synagogue or local sisterhood affiliate. In fact, in a move toward maximal inclusivity, WLCJ membership is now open to all those who identify as women and who are either Jewish or associate themselves with the Jewish community.

Education/Programming

Always operating on the premise that “Education is the lifeline of sisterhood,” Women’s League has promoted Jewish literacy and leadership for women by creating programs and providing resources for sisterhoods related to adult education, books, libraries, creative handicrafts, Jewish family living, Judaica shops, and music. Early publications provided guidance and instruction for Sabbath and holidays, with The Three Pillars: Thought, Worship and Practice (1927) by Deborah Melamed serving as the cornerstone of educational programs. Women’s League also published the popular Jewish Home Beautiful (1941) by Betty D. Greenberg and Althea O. Silverman. This book, based on a popular pageant of the same name and replete with traditional recipes, illustrations of table settings, and music, served as a guide for creating Jewish homes filled with beauty and spirituality.

Women’s League’s concern with enhancement of Jewish ritual and observances is exemplified by the magnificent Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.sukkah at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS,) which WLCJ maintained as a special project throughout the years. After Schechter’s death, Adele Ginzberg, founder and active member, steered this project for decades, decorating the sukkah with fresh fruits, vegetables, and greenery. In the 1970s, Women’s League dedicated a Sukkah Endowment Fund in the name of “Mama G” to underwrite increasing costs, and it has maintained responsibility for the sukkah’s decoration.

After World War II, Women’s League’s educational activities expanded tremendously in response to the increased pace of growth of the Conservative Movement. Ginzberg initiated a Girl Scout project in 1946 that led to the establishment of the Menorah Award for Jewish Girl Scouts, in order to stress the importance of Jewish education and encourage Jewish scouts to participate in synagogue activities (and to parallel the Ner Tamid Award for Jewish Boy Scouts). The Judaism-in-the-Home project introduced in the 1950s, chaired by Rose Goldstein and Anna Bear Brevis, produced instructional materials to teach sisterhood women the meaning of Jewish holidays and rituals; a series of Oneg Sabbath programs based on the weekly Torah portions was published as well.

Women’s League’s magazine, Outlook, was published from 1930 to 2007. From 2007 to 2015, WLCJ joined with United Synagogue and the Federation of Jewish Men Clubs in publishing CJ Magazine. By 2016, Women’s League had returned to publishing as an independent organization; from 2016 to 2019, it produced New Outlook as a newsletter, after which it switched over to its current digital format.

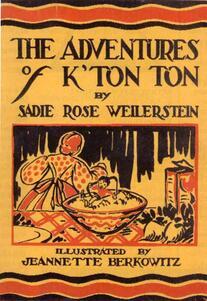

Outlook’s initial mission was to keep sisterhood members in touch with each other and the other organizations with which the league was affiliated; it also served as a means for members to voice their opinions. Articles focused on Jewish cultural subjects and contemporary issues, as well as on the achievements of the seminary and United Synagogue. Each issue carried messages from the national president, national activity chairpeople, and branch presidents. One of the most popular features was the Children’s Corner, which introduced thousands of readers to Sadie Rose Weilerstein’s fictional character K’tonton beginning in 1935.

In 1959, Hadassah Nadich initiated the organization’s first calendar diary. These calendar guides promoted Jewish activities in the home, synagogue, and community. Still published annually, and available for purchase on the WLCJ website, they were distributed to all sisterhoods so that local leaders could incorporate educational elements into their projects. In 2004, in celebration of 350 years of Jewish settlement in North America, Women’s League created a traveling exhibit, “Beauty, Brains and Brawn,” that featured women from across the United States who contributed to American Jewish life. By the 2020s, WLCJ had fully embraced the digital age. While some printed publications remain available to affiliates and the public, WLCJ has greatly expanded access to digital downloads, video recordings, and streaming of educational materials, classes, and webinars.

Intensive Jewish study for its own sake has long been a priority of Women’s League. In 1931, the Women’s Institute of Jewish Studies of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America was initiated through the league’s Metropolitan Branch in cooperation with other leading Jewish women’s organizations, including Hadassah, the National Council of Jewish Women, Ivriah, the Federation of Jewish Women’s Organizations, and Women’s League for Palestine. The purpose of the institute was “to offer women attending its classes an opportunity to equip themselves for making a constructive approach to the problems of contemporary Jewish life, and a broad perspective of modern Jewish problems.”

Beginning in 1977, Women’s League organized its own annual institute consisting of two semesters of classes taught by JTS faculty members. Similar programs developed in Philadelphia, Southern New Jersey, Washington, D.C., and east and west coast Florida have been maintained in various regions throughout the years. In a similar vein, one of WLCJ’s most successful programs has been the Leadership Institute, first developed in 2003. This institute continues to offer women the opportunity to enhance their leadership skills—empowering them to take on positions of leadership in their communities and in Women’s League.

In 2001, Women’s League, together with Alice Shalvi, then rector of the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, launched a Women’s Institute in Israel. It attracted hundreds of women for a day of study with scholars in Hebrew, English, Russian, and Spanish. This annual event developed into an even more robust series in partnership with the Schechter Institutes, Midreshet Schechter, and the Women’s League of Masorti Judaism (as the Conservative Movement is known outside the United States). During the 2020 pandemic restrictions, the Masorti Women’s Day of Study was brought online, virtually bringing together hundreds of Masorti women from throughout the world.

Even before the 2020-2021 pandemic restrictions, online learning had become a central component of Women’s League’s educational programming and community building, and these efforts were redoubled during that period. In 2020-2021 alone, Women’s League’s online offerings included five different levels of Hebrew language classes, intensive study of Mishnah Brachot, poetry workshops, the Women’s League Reads book club, and more. WLCJ’s online presence has also allowed its members to access classes and programs from affiliates all over the country, enabling individual sisterhoods to widen their connections and vastly multiplying the learning opportunities for all.

Women’s League members have long sought out additional opportunities to advance their knowledge and observance of Jewish ritual. Inspired by the burgeoning Jewish feminist movement, many women chose to undertake the necessary studies to become Lit. "daughter of the commandment." A girl who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbat mitzvah as adults. Kolot BiK’dushah was formed in 1993 to encourage women nationwide to lead a religious service and/or read from the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah. The society of Kolot BiK’dusha continues to recognize those women who achieve these levels of proficiency. As the Conservative movement evolved in relation to egalitarianism, Women’s League members often worked as leaders and change agents to promote women’s fuller participation in services. WLCJ encourages women to practice what were traditionally seen as “male” A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvot, such as donning Four-cornered prayer shawl with fringes (zizit) at each corner.tallit and Phylacteriestefillin, training women in performing these mitzvot through online and in-person sessions. It now participates with the Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs in the World Wide Wrap sponsored by the USCJ. The inroads WLCJ has made in nurturing women’s participation in these mitzvot was made apparent at its 2020 (virtual) convention, when over 150 of the 1,200 women praying together did so in tallit and tefillin.

Makom B’Yachad was begun in 2020 in order to provide members the opportunity to recite Lit. (Aramaic) "holy." Doxology, mostly in Aramaic, recited at the close of sections of the prayer service. The mourner's Kaddish is recited at prescribed times by one who has lost an immediate family member. The prayer traditionally requires the presence of ten adult males.Kaddish remotely despite pandemic restrictions. Beginning with the daily study of Psalms and continuing with Pirke Avot (Ethics of the Ancestors) and the weekly Torah portion, Makom B’Yachad has developed into a mutually supportive community of 60-80 global participants. Gathering daily to study, say kaddish, and pray for healing, participants have also remotely visited the sick, attended virtual Lit. "seven." The seven-day mourning period held following the death of an immediate family member: spouse, parent, child or sibling.shivah gatherings, and served as social and spiritual buoys for one another during the pandemic. This program embodies WLCJ’s more recent focus on the wellness of its members, encouraging affiliates to organize programming related to women’s physical and emotional health.

Fundraising

Women’s League has been especially closely linked to the Conservative Movement’s institutions of higher education and the welfare of their students—which initially meant support for JTS, as the sole institution of that kind affiliated with the movement. Beginning in 1934, this interest was formalized through the establishment of an educational fund to which members contributed an annual amount to assist the seminary in its work; it was renamed Torah Fund after 1942. Initially it was suggested that each member contribute a minimum of $6.11 (the Hebrew numerical equivalent of the word “Torah”); in 1945, the Chai Club was formed to encourage women to increase their annual contributions to eighteen dollars. Torah Fund pins, first introduced in 1957, are designed annually to encourage Women’s League members to donate to Torah Fund and are worn to reflect their dedication to the seminaries and members’ level of giving. Over the years, monies raised have supported JTS scholarships, residence halls, library, programs, and other JTS facilities.

Two major initiatives are noteworthy. In 1958, Torah Fund focused its support on the creation of a dormitory for women students through the Mathilde Schechter Residence Hall campaign. In response to changing needs, the Mathilde Schechter Residence Hall opened as a coeducational dormitory for seminary undergraduates in 1976. In 1995, Torah Fund refurbished the seminary synagogue, which was dedicated as the Women’s League Seminary Synagogue. Over time, with the proliferation of the Conservative Movement’s affiliated higher educational institutions, WLCJ expanded Torah Fund’s support to include the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies (Los Angeles, CA), Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem, Israel), Seminario Rabinico Latino.americano (Buenos Aires, Argentina), and Zacharias Frankel College (Potsdam, Germany). Monies raised by Torah Fund currently support scholarships at these institutions along with JTS.

Social Action

The "Yankee" Jewish women of the first half of the twentieth century created the infrastructure of American-Jewish women's organizational activities. The founding of synagogue sisterhoods began with the Reform National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods in 1913, followed by the Women's League for Conservative Judaism in 1918, and the two Orthodox sisterhoods, Mizrachi Women’s Organization of America (AMIT) in 1925 and Emunah in 1935. Pictured here is the Orthodox Congregation B'nai David Sisterhood of Detroit, Michigan, ca. 1950. Among those seated are Rebbetzin Yetta Sperka (top left), wife of the synagogue Rabbi Joshua Sperka; Mrs. Hyman Adler (top right), wife of the congregation's cantor; and Mrs. David J. Cohen (second row, center).

Institution: Ahava Rivka Sperka.

As part of its commitment to Jewish values WLCJ has long been involved with social action. It has supported human and women’s rights, civil rights, social justice, and care for the poor, hungry, and homeless. One early initiative was league women’s work with the Jewish Braille Institute as transcribers of Braille for the Jewish blind. The first Hebrew-English prayer book in Braille was underwritten by WLCJ in 1954.

During World War II, Women’s League was active in the Supplies for Overseas Survivors Drive and in collecting food and clothing for the Joint Distribution Committee. Members also trained to assume needed tasks, including serving as Red Cross instructors and air raid wardens. Sisterhoods in areas of war industry turned their social halls into emergency hospitals; some organized kosher kitchen units for civilian populations in the event of catastrophe. Beginning in 1933, concerned about the deteriorating condition for Jews in Nazi Germany and its occupied territories, Women’s League called for personal sacrifice on the part of its members to aid the war efforts.

After the war, Women’s League continued its involvement with issues of public concern. The first resolution adopted in 1950 advocated the elimination of discrimination in public places. Over the decades, Women’s League has supported a mostly liberal political and social agenda, guarding civil liberties in the McCarthy era, advocating the separation of church and state, and calling for government funding to ameliorate social conditions of the poor and the aged. Especially concerned with women’s issues, Women’s League passed resolutions urging the adoption of the Equal Rights Amendment. In recent years, WLCJ has passed resolutions speaking out against racism, gun violence, violence against women, and human trafficking and supporting reproductive choice (including abortion rights), full equal rights for LGBTQ+ individuals, a ban on assault weapons, and racial justice.

WLCJ has actively followed through on these stances through education of its members and outreach programs. Women’s League effects change mostly through providing educational opportunities, program ideas, and hands-on initiatives to its affiliates. One such program, Mathilde’s Mentionables, collected over 5,000 bras for women in shelters or victims of natural disasters at the 2017 triennial convention and continued as an ongoing project in affiliated sisterhoods. Focusing on food insecurity in 2021, WLCJ’s Stock the Shelves project encourages affiliates to collect food donations for local food pantries, providing affiliates with materials and guidance in how to achieve their goals.

Women’s League was also an early and vocal advocate for egalitarianism in Conservative Jewish religious life. At its national convention in 1972, women were called to the Torah for an Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah, a move that was considered a radical innovation at the time; they also voted to remove their husbands’ names from the official roster. An opinion poll taken at that time revealed that an overwhelming majority of members believed that women should be elected to congregational boards, be permitted to read from the Torah, and be able to initiate Jewish divorce proceedings. Over 60 percent also called for women to be counted in the minyan [quorum of ten] and called to the Torah for an aliyah. In subsequent years, delegates voted three-to-one for the ordination of women by JTS (1980) and the acceptance of women as cantors (1990). Resolutions throughout the period forcefully called for equality in Jewish life, a resolve generally adopted in the Conservative movement at large, as the movement shifted toward full equality and inclusivity. That these changes in the movement have come to fruition was demonstrated in WLCJ by the hiring in 2018 of Rabbi Ellen S. Wolintz-Fields as Executive Director, the first female rabbi to head the organization. In 2020 Rabbi Wolintz-Fields was joined on staff by Rabbi Margie Cella as Education Programing Coordinator.

Israel has always been a high priority for the organization. In 1923, National Convention delegates voted unanimously “for unqualified support of all agencies engaged in the upbuilding of Palestine.” By 1926, the league had embarked on a project to raise funds for the construction of the Yeshurun Synagogue in Jerusalem. Since the creation of the State of Israel, Women’s League has continued its unwavering support—passing resolutions supporting the need for foreign aid and security and criticizing Arab boycotts and propaganda and United Nations discriminatory policies—while in 2004 voicing support for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. More recently WLCJ resolutions supported pro-Israel activism on campuses and opposed boycott, divestment, and sanction (BDS) efforts.

Women’s League has also turned its attention to issues pertaining to civil rights and gender and religious equality in Israel. It passed resolutions asserting the need for religious pluralism, the recognition of the Masorti (Israeli Conservative) Movement, funding for TALI schools (enhanced Jewish study in Israeli public schools with roots in the Masorti movement,) and access for egalitarian prayer at the Western Wall. It has fought vigorously against calls to amend the Law of Return and has lent support to Masorti congregations and institutions in Israel, along with their women’s groups. Additionally, WLCJ maintains a staff member in Israel to act as liaison between the North American and Israeli groups.

Concern for world Jewry resulted in resolutions on behalf of the Jews of Ethiopia, the Soviet Union, and Syria. In addition, efforts have been made to connect with women in Masorti communities in Europe, South America, and Africa, including nascent ties with women of the Abayudaya community in Uganda.

Beginning with an invitation to the White House Mid-Century Conference on Youth in 1950, Women’s League has been included in major assemblies of the nation’s leading organizations—participating in conferences on civil rights, children and youth education, and racial equality. Since 1952, Women’s League has also been an accredited nongovernmental observer at the United Nations. Within the Jewish world, the WLCJ president and executive director serve as representatives to the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations. In 1980, it gained autonomous affiliation with the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council, now known as the Jewish Council for Public Affairs (JCPA.)

By the mid-1970s, Women’s League had come of age—symbolized by two important events. First, in 1969, it moved out of the seminary, where it had been housed since its inception. Three years later, the organization changed its name to Women’s League for Conservative Judaism, signifying that it was no longer a subsidiary of United Synagogue, but rather an independent arm of the Conservative Movement with a distinct presence and voice.

While shrinking demographics of American Jewry—and those of the Conservative Movement in particular—present a challenge, Women’s League for Conservative Judaism remains firmly committed to the perpetuation of Conservative/Masorti Judaism in the home, synagogue, and community through the engagement of Jewish women. By means of its programs, publications, classes and affiliated sisterhoods, it links women with one another, providing mutually supportive community that promotes social connection, wellness, religious commitment, and spiritual wellbeing. Women’s League nurtures “the role women play as keepers of the flames of mitzvot, family, study, Israel, Torah, and community” and empowers women by expanding leadership skills and opportunities.

Presidents of Women’s League For Conservative Judaism

Mathilde Schechter 1918–1919; Fanny Hoffman 1919–1928; Dora Spiegel 1928–1946; Sarah Kopelman 1946–1950; Marion Siner 1950–1954; Helen Sussman 1954–1958; Syd Rossman 1958–1962; Helen Fried 1962–1966; Evelyn Henkind 1966–1970; Selma Rapoport 1970–1974; Ruth Magil Perry 1974–1978; Goldie Kweller 1978–1982; Selma Weintraub 1982–1986; Evelyn Auerbach 1986–1990; Audrey Citak 1990–1994; Evelyn Seelig 1994–1998; Janet Tobin 1998–2002; Gloria B. Cohen 2002–2006; Cory Schneider 2006-2010; Rita Wertlieb 2010-2014; Carol Simon 2014-2017; Margie Miller 2017-2020; Debbi Goldich 2020-present.

Goldich, Debbi. Interview with Helene Herman Krupnick, June 2021.

Kirschner, Janet. Interview with Helene Herman Krupnick, June 2021.

Nadell, Pamela S. Conservative Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Rubin, Illene. Interview with Helene Herman Krupnick, June 2021.

Schneider, Cory. Correspondence with Helene Herman Krupnick, June 2021.

Schwartz, Shuly Rubin. Correspondence with Helene Herman Krupnick, June 2021.

Seventy-Five Years of Vision and Voluntarism. 1992.

The Sixth Decade: 1968–78. New York: 1978.

United Synagogue of America. They Dared to Dream: A History of National Women’s League, 1918–68. New York: National Women’s League of the United Synagogue of America, 1967.

Wolintz-Fields, Ellen S. Correspondence and interview with Helene Herman Krupnick, June 2021.

Women’s League Outlook (1930–2002).

Women’s League for Conservative Judaism website, www.wlcj.org.