Mae Rockland Tupa

Paper-cutter, printmaker, and textile artist Mae Rockland Tupa is an accomplished multimedia artist and author whose work has helped shape the field of Jewish Americana and explores themes of Jewish identity, history, and culture. Born in the Bronx, New York, to Eastern European immigrants, Mae graduated from the Music & Art High School in 1953 before continuing her education at Hunter College, Alfred University's College of Ceramic Design, and the University of Minnesota. She published seven books, including the pioneering 1973 text The Work of Our Hands: Jewish Needlecraft for Today. Her work is housed in the collections of numerous institutions, such as The Jewish Museum in New York City. As of 2025, she is the proud mother of three children, seven grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

Family

Mae Cecilia Rockland Tupa (née Shafter) was born on December 18, 1937, in the Bronx, New York, the daughter of Eastern European immigrants. Much of her art is inspired by her Jewish identity, Yiddish heritage, and her family’s immigration experience.

Mae’s father, Yudel Schachter, was born in Ukraine in 1907. Yudel’s father David immigrated to the United States in 1908 and operated a commercial junkyard in Rockland, Maine. Following the death of his mother, Raisel, Yudel immigrated to the United States in 1922 with his brothers and grandmother. He first settled in Maine, where he was reunited with his father. After changing his name to Joe Shafter, he moved to New York City to apprentice as a glazier with his uncle Max; he worked as a glazier for the rest of his life and was instrumental in the founding of the Glaziers Union Local 1087.

Mae’s mother, Shayna Bella Dunsky, was born in Poland in 1906. After immigrating to the United States, she settled in the Bronx, New York, with extended family. Her parents, Judah Dunsky and Chaya Feygel Nevinsky, perished in Poland during the Holocaust. Mae’s mother told her that the name “Dunsky” stemmed from the Dun River and that several members of the family were potters who collected clay from its banks. Mae cites this story as the reason she fell in love with ceramics at a young age.

Mae’s parents met at the Yiddish Theater in New York City. Joe, who always dreamed of becoming an actor, attended Saturday evening performances whenever he could afford tickets. Smitten by a woman sitting across the aisle, he offered to walk her home. They married in 1928 and had three daughters: Rosalyn (who passed away as an infant from pneumonia), Mae, and Linda. Joe and Bella, whose lives inspired much of Mae’s art, died in 1979 and 1980, respectively.

Childhood

Raised as a “pink diaper baby” (a child born to communist or socialist parents), Mae attended a secular Yiddish school in the Bronx that was associated with the Workmen's Circle (renamed the Workers Circle in 2019). Her family was not especially observant but they often celebrated the Jewish Sabbath. To this day, SabbathShabbat is one of her favorite aspects of Jewish life. “Shabbos is the thread that holds Jews together,” she remarked during an interview with scholar Jodi Eichler Levine.

Mae and her parents only spoke Yiddish at home until she was five years old, when she came home from public kindergarten one day and demanded that the family speak English because “I wanted to be an American!”

Mae began making art at a young age. She cited her Irish kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Kirsinger, and her family for supporting her creative endeavors. Before she mastered English, Mae relied on illustrations to understand the books her teacher shared with the class. Inspired by these illustrations, she began to make her own drawings. Her mother often allowed her to draw on the baseboards of their apartment because, as Mae explained, she could easily clean them.

As Mae grew older, her mother taught her papercutting, sewing, and embroidery. Her mother had suffered from spinal meningitis as a child; because it was difficult for her to use a needle and thread, she taught her daughter basic stitches and patterns, including some inspired by her own mother’s work. “It was a way for her, through me, to connect with her mother,” she told the author during a 2024 interview. When Mae was a child, her grandmother Chaya sent the family a work of embroidery. She further developed her embroidery skills by copying the stitches she saw on the cloth. The embroidery, which her mother framed, depicts a seated dog and two boys smoking cigars. “I have always treasured it,” Mae said. “It has followed me around the world.”

As a child, Mae also found inspiration in art by her cousin, Philip Gips, who attended the High School of Music & Art (M&A), a public high school in Harlem that later merged into the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & the Arts. Following in her cousin’s footsteps, Mae attended M&A, where she fell in love with ceramics.

Living Abroad

At the age of seventeen, shortly after completing her freshman year at Hunter College, Mae married a Jewish man named Michael Aaron Rockland. (His surname is coincidentally the same as the town in Maine where her relatives lived.) She continued her education for one year at Alfred University's College of Ceramic Design. After Michael was drafted into the U.S. Navy, they moved to Japan. The young couple lived in Isshiki, a coastal neighborhood in the town of Hayama. Mae set up a ceramics studio on the naval base and taught classes for the servicemen.

After living in Japan for a year, the couple moved to Minnesota. While Michael pursued a graduate degree in American Studies, Mae earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Minnesota, where she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and studied printmaking, in part because the university’s ceramics department was too far from where they lived. Over time, she fell in love with the medium. She gave birth to two sons, David and Jeffrey, while living in the Midwest.

On balancing her responsibilities as an artist, student, wife, and mother, Mae told Eichler-Levine, “I thought of myself as a juggler.”

In 1961, Michael entered the United States Foreign Service. The family moved to Buenos Aires, where Mae had her first solo exhibition at the Galeria El Portico in 1963. Two years later, they moved to Madrid, where Mae became involved in the local art community. She spent much of her free time at a nearby art studio, where she honed her printmaking skills. She developed close friendships and exhibited with Spanish artists. In 1967, Mae gave birth to a daughter, Keren, at the Torrejón Air Force base outside of Madrid. Less than a year later, the family returned to the United States, living briefly in Washington, DC, before settling in Princeton, New Jersey.

Written Works

Mae began to teach at the Princeton Art Association and founded a sewing group at her local Conservative synagogue, the Princeton Jewish Center, teaching congregants how to make challah covers, Four-cornered prayer shawl with fringes (zizit) at each corner.tallit bags, and other kinds of Judaica. This experience inspired her to begin incorporating Jewish themes, ranging from the Holocaust to biblical stories and Yiddish folk tales, into her own work. She also joined the Pomegranate Guild of Judaic Needlework and exhibited her work at Princeton’s Nassau Gallery.

Over time, Mae developed a number of designs for Jewish ceremonial objects. Several women in her sewing group encouraged her to compile these designs into a book. She was eventually introduced to Beverly Coleman, an editor at Schocken Books. Carrying a few samples of her drawings and needlework, she took the bus from Princeton to New York City, unsure what to expect. She returned home with a book deal.

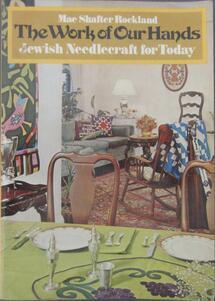

Mae’s first book, The Work of Our Hands: Jewish Needlecraft for Today, was published in 1973. The book’s title was inspired by Psalm 90, which reads, “May the favor of the Lord, our God, be upon us; let the work of our hands prosper.” As historian (and Mae's daughter) Keren R. McGinity described, the book “took the world of American Judaica by storm. Finally, here was a book that surveyed the abundant Jewish tradition of art and explained how to enlarge upon that tradition in terms of symbols, colors, and objects” (McGinity, 2013). The collection included designs for myriad projects, from needlepoint and embroidery to quilting and patchwork. The book taught readers to create both religious and secular objects, ranging from kippot (skull caps) to tablecloths. Mae even designed her own font for the Hebrew alphabet; artists today continue to emulate her stunning design for the alef bet letters. The Work of Our Hands was very well received. Readers sent Mae photographs of their creations, while individuals and communities began commissioning her to create a wide variety of pieces.

Mae went on to publish six more books. After realizing she had forgotten to mention Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah in her first book, she published The Hanukkah Book in 1975, followed by The Jewish Yellow Pages: A Directory of Goods and Services (1976); The Jewish Party Book: A Contemporary Guide to Customs, Crafts, and Foods (1978); The New Jewish Yellow Pages (1980); an updated edition of The Hanukkah Book: Games, Activities, and Gift Suggestions for the Whole Family (1985); and The New Work of Our Hands: Contemporary Jewish Needlework and Quilts (1994).

"Miss Liberty"

In 1974, Mae constructed “Miss Liberty,” a large Hanukkah menorah constructed out of plastic Statue of Liberty souvenirs. Housed in the permanent collection of The Jewish Museum in New York City, “Miss Liberty” is one of her most iconic works of art.

The idea of “Miss Liberty” came to Mae when she was working on The Hanukkah Book. One day, she passed a souvenir shop in downtown Manhattan selling plastic Statues of Liberty. They reminded her of a childhood experience at her Yiddish schule (school) when she and eight fellow students each held a candle forming a human hanukkiah. After purchasing several, she transformed the arms into candle holders and built a base covered in American flags and quotes from Emma Lazarus’s famous poem “The New Colossus.”

Mae later created several additional versions of “Miss Liberty” for institutions such as the Boston Workers Circle and the Jewish Museum in Berlin, as well as for private collections. Some versions include statuettes depicting different races. Inspired in part by childhood memories and her own family’s immigration story, her work is also a political statement about the ambivalent history of immigration in the United States.

According to historian Jonathan D. Sarna, Mae’s “Miss Liberty” hanukkiah reflects a core theme in American Jewish culture that he calls “the cult of synthesis,” the widespread and longstanding “belief that Judaism and Americanism reinforce each other” (Sarna, 1999).

Second Marriage

After 22 years of marriage, Mae and Michael separated in 1977. Mae moved to Brookline, Massachusetts, with her daughter while her older two sons remained in New Jersey, one to finish high school and the other college.

Soon after arriving, Mae was introduced to Myron Alfred Tupa, a talented artist, avid collector, and art teacher at the local high school, and quickly discovered a kindred spirit. In 1979, the two were married in the living room of the Brookline home they had purchased and remodeled together. Myron, raised Catholic, formally converted to Judaism twenty years after the couple wed.

In Brookline, the couple established a studio in which they could both pursue their artistic passions. In 1983, after earning a degree in interior design, Mae founded Metatron Designs and worked as an interior designer.

Over time, Mae gradually moved away from paper-cutting and printmaking to focus her creative energy on quilt-making. Her masterful and intricate quilts are inspired by a wide range of subjects, including the immigrant experience, the history of Jews in Medieval Spain, and Yiddish folktales. She made quilts to be used on beds and to be hung on walls. The art quilt “Promise” is a 4’ x 4’ masterpiece representing her parents’ and many others’ journeys to America. It was exhibited in Europe before settling at her daughter’s home, in safekeeping for one of Mae ’s granddaughters, along with many challah covers she made between 1956 and 2020.

In 1992, Mae founded the Boston chapter of the Pomegranate Guild of Judaic Needlework. Her involvement lasted many years, and she spoke at several of the Guild’s national conventions. “It’s great to be surrounded by lots of Jewish schmattes” (a Yiddish term that refers to shabby objects, specifically garments), she told Eichler-Levine in 2022.

In the early 2000s, Mae joined “A Besere Velt” (A Better World), a Yiddish chorus organized through the Boston Workers Circle. Founded in 1997, the 80-member chorus has collaborated with acclaimed Yiddish museums and performed throughout the New England and New York areas. “Yiddish is my mamaloshen (mother tongue),” Mae remarked. “I love being a part of the chorus.” In May 2024, she sang with her chorus at Boston’s Fenway Park in celebration of Jewish American Heritage Month.

Home Away from Home

Mae ’s roots in Maine run deep. In the 1970s, after visiting her cousins in Rockland, she rented a cabin farther north and subsequently purchased one in Bucksport in 1976, which she and Myron spent four decades enjoying .

When she was growing up, Mae’s mother would tell her about the “Golden Age” of Jewish culture in Spain, before Jewish communities were expelled. Her love for Spanish culture only grew in the 1960s, when she lived in Madrid as the wife of a diplomat. For years after she remarried, Mae dreamed of bringing Myron to Spain. In 1986, on their first trip there, the couple visited the village of Vilafames in the province of Castellón, about an hour from Valencia. Falling in love with the landscape and community, they eventually bought a medieval ruin at the edge of town, with deep stone buttresses and gothic arches. Over the next several years, the couple created a summer home there.

Legacy

Mae's work helped shape the field of Jewish Americana. She has been instrumental in the preservation and transformation of Jewish art and craft traditions. “I love being Jewish,” Mae told the author. “I feel very much part of the Jewish people, and I am very proud that I’ve been able to contribute to it.”

As scholar Jodi Eichler-Levine noted in her book Painted Pomegranates and Needlepoint Rabbis, Mae’s publications made craft practices, such as sewing, more accessible to Jews during the DIY movement of the 1970s and 1980s, which continues in the present. Following a long period of assimilation, many communities had become interested in reviving Jewish cultural traditions. Moreover, her acclaimed piece, “Miss Liberty,” further advanced Jewish feminist and political art in the United States. Throughout her career, Mae put forth new ways of creating art about America through Jewish interpretive frames. Her work continues to inspire artists and crafters to reimagine Jewish traditions.

Mae’s work is housed in the permanent collection of The Jewish Museum in New York City, as well as the collections of the Berlin Judisches Museum, the Skirball Cultural Center, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the National Library of Spain, and numerous universities, Jewish congregations, and private collections.

“I feel very lucky to have been given the gift of both seeing and making things,” Mae said during a 2024 interview. When asked if she has any advice for younger generations of artists, she responded, “If you want to make art, make it.”

Selected Works by Mae Rockland Tupa

The Work of Our Hands: Jewish Needlecraft for Today (1973)

The Hanukkah Book (1975)

The Jewish Yellow Pages: A Directory of Goods and Services (1976)

The Jewish Party Book: A Contemporary Guide to Customs, Crafts, and Foods (1978)

The New Jewish Yellow Pages (1980)

The New Work of Our Hands: Contemporary Jewish Needlework and Quilts (1994)

Eichler-Levine, Jodi. Painted Pomegranates and Needlepoint Rabbis: How Jews Craft Resilience and Create Community. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

McGinity, Keren R. “Mae Rockland Tupa: Artist and Author.” Jewish Women’s Archive, May 14, 2013. https://jwa.org/blog/mae-rockland-tupa-artist-and-author.

Sarna, Jonathan D. “The Cult of Synthesis in American Jewish Culture.” Jewish Social Studies 5, no. 1/2 (1999): 52-79.

Tupa, Mae Rockland. Interview by Jodi Eichler-Levine, October 12, 2022.

Tupa, Mae Rockland. Interview by Joshua Kurtz, July 24, 2024.