Anna G. Sherman

One of the unsung heroes of the Hebraist movement in the United States, Anna G. Sherman inspired hundreds of students, mostly adult women, to connect to their Judaism through the study of Hebrew. Born to Jewish immigrants to Palestine in 1897, Sherman and her family moved to New York City in her early childhood. She taught Hebrew at the Teachers Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary, her alma mater, for nearly forty years,., crafting a feminist pedagogy that was inspiring before its time. It centered her belief that the Hebrew language is a key aspect of Jewish identity, a value she shared with her mentor Mordecai Kaplan, whom she met early in her career.

Anna G. Sherman was one of the unsung heroes of the Hebraist movement in the United States. A passionate believer in Hebrew as the vehicle for nurturing Jewish identity, Sherman taught adults, mostly women, at the extension schools of the Teachers Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary for approximately forty years. These classes, variously known as the Israel Friedlaender Classes, the Seminary School of Jewish Studies, or the Women’s Institute, attracted about 225 students annually, according to a Teachers Institute report in 1939. A graduate of the Teachers Institute in 1916 and winner of an award for the outstanding essay in the class, Sherman met Mordecai M. Kaplan (1881–1983), who had been recruited to lead the JTS school of education in 1909. While at the Teachers Institute, first as a student and later as an instructor, Anna G. Sherman crafted a pedagogy inspired by Ahad ha-Am (1856–1927), Samson Benderly (1876–1944), and Mordecai Kaplan. Although never officially a member of the coterie of influential Jewish educators known as The Benderly Boys (which included several women) because of her lack of secular credentials, Anna G. Sherman came into their inescapable orbit while a student at the Teachers Institute and a member of the faculty.

Early Life & Education

Anna G. Sherman’s exact birth date is somewhat unclear because of the chaotic state of official records in pre-WWI Palestine. The daughter of Shlomo Grossman (1860–1928) and Sara Weinstein (d. 1928), Hanna (Anna) was born in Kastina in Palestine around 1897. Shlomo, born in 1860, was orphaned in 1874. The Grossmans, like most of the settlers of Kastina (now known as Be’er Tuviyyah) came from Bessarabia. Founded by Hovevei Zion in 1887 and supported by the largesse of the Baron Edmond James de Rothschild (1845–1934), Kastina was a pestilent and unproductive place. Grossman spoke nothing but Hebrew to his children and begrudgingly resorted to Yiddish to communicate with his wife. In 1905 or 1906, exhausted by illness and futility, he reluctantly moved to New York with his wife and three surviving children, Ovadiah, the eldest, Shoshana (who died of a respiratory infection shortly after arrival), and Hanna, the youngest, heir to her father’s love of Jewish texts, Hebrew, and the land of Israel.

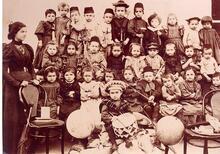

While a student at Julia Richman High School, Hanna, now known as Anna, gave Hebrew lessons to supplement the family’s meager income. Her reputation brought her to the attention of Frieda Schiff Warburg, who hired the attractive young redhead to give her lessons at the Warburg mansion. In 1923, Anna began teaching at her beloved alma mater, the Jewish Theological Seminary, an association which lasted until the early 1960s.

Time in Jerusalem

After a tragic year in which Anna Grossman suffered a series of disastrous personal losses, she decided to leave New York in order to study Hebrew in Jerusalem. In 1931, at a Shabbat tea at the home of Lord Herbert Samuel (1870–1963), Anna met Dr. Earl Mayo Sherman (1903–1973), an idealistic young dentist who had come to Jerusalem to take over a public clinic newly established by Hadassah. She married him and within three years became the mother of Varda (b. 1932) and twins, Ori and Ari (b. 1934).

Like her father, Anna Sherman found herself unable to remain in Israel. Weakened by childbirth and suffering from chronic kidney disease, she sadly left Jerusalem with her children in 1936, sustained by the slimmest promise of teaching in the Women’s Institute of JTS. Eventually she received a full complement of classes and became a mainstay of the extension school classes. It was Frieda Schiff Warburg, always grateful to her teacher, who offered an interest-free loan to Dr. Sherman, enabling him to begin his dental practice in New York.

Hebrew Pedagogy

Anna Sherman’s private papers bear witness to her belief in the transformative power of language to create an alternative community. Her pedagogy was fueled by a belief in Hebrew as the key to Jewish identity, a philosophy shared by her mentor, Kaplan, as well. Teaching Hebrew was her vocation and her passion. As one of her students remembers, “If she never got a penny, she still would have taught.” Hers was a feminist pedagogy based on connectivity, building relationships in and out of the classroom, and multiple teaching strategies. She instituted a co-curricular club, the Raanana, which she taught without pay. She continued to correspond with students decades after they attended her classes. Her ivrit be-ivrit classroom was enlivened by songs, skits, and quick sketches on the blackboard. Foreshadowing a later generation of feminists, Sherman excelled at consciousness-raising. Unlike the Benderly Boys (and Girls) whose major focus was teaching children, Sherman always focused on adult education and developed an expressive pedagogy directed at that audience. Unlike Benderly, Sherman could never be called a secularist. Like her mentor and rabbi, Kaplan, her joy was “in retrieving lost souls and bring them closer to Judaism and to Hebrew culture” (Sherman, Spring 1956).

Upon her retirement, Anna G. Sherman kept busy with Zionist meetings, interfaith lectures, reading Hebrew journals, and meeting with her ever-shrinking circle of Hebraists to read poetry and prose. She died in New York in 1980 after an illness of eight years.

Sherman, G. Anna. “Why adults study Hebrew.” Adult Jewish Education, 1956: 20–22.