Regina Schoental

As a woman, Regina Schoental fought her way into chemistry departments across Europe and the world. As a chemist, Schoental produced breakthrough studies about cancer- and other disease-causing substances. Her research took her around the world, and her influence in the realm of cancer research and toxicology traveled just as far.

Our knowledge of toxic substances in plants, of mycotoxins, and of aromatic (“coal tar”) and certain other chemicals that cause cancer owes much to the pioneering work of Regina Schoental. Her research has contributed to industrial hygiene, diet, including nutritional factors in carcinogenesis, the understanding of the relationship between structure and activity in natural and synthetic carcinogenic organic chemicals, and toxicology in general.

Early Life and Education

Schoental was born on June 12, 1906, in Dziatoszyce, Poland, to Gershon Schoental (1872–1942), a land owner and banker, and Dina Schoental (née Eisenberg, b. Cracow, 1874–1942). Her parents and most of her close family perished in the Holocaust.

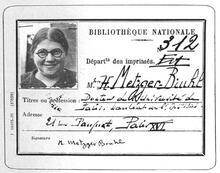

Schoental attended the Cracow High School for Girls and studied chemistry at Cracow’s Jagellonian University, where she received her master’s degree in 1929 and her Ph.D. in 1930. She undertook research in the university’s Clinical Laboratory for Cancer Research in the mid-1930s and at the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the Medical Academy during 1936–1938 under Professor Oszacki. She was encouraged to go to England by Joseph Needham, whom she met when he visited Cracow in 1938. “I wrote to [Ernest Lawrence] Kennaway and without waiting for his reply arrived in London on the 10th November, 1938.” The next day she appeared in Kennaway’s office, where he advised her that there was no space: “The Chester Beatty [Cancer Research] Institute was then under construction.” (Schoental to Sir Edward Abraham, February 17, 1981.) She recorded that “Neither Henry Dale nor John Gaddum were willing to accept me into their respective laboratories. In desperation, with a visa which was only valid for one month, I wrote in Polish to David Keilin [in Cambridge] explaining my situation; I knew that he had come from Poland. By return I received his reply, inviting me to come to Cambridge. … He accepted me at the Molento [Institute]. … Extension of my visa and permission to receive money from home followed his intervention.” Her surviving papers suggest that in the late 1930s she considered joining the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where cancer research was also carried out.

Research from Cambridge to Kenya

Schoental spent just a few weeks in Cambridge. Following Needham’s suggestion she applied to Oxford, where she was accepted by Howard Florey. There, in 1939, she joined Isaac Berenblum, Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology of Oxford University as a volunteer in the investigation of metabolism of cancer tissues. “The outbreak of war interrupted the cancer research. Florey and Chain suggested that I try to isolate the antibiotic substances from Ps. Pyocyanea, which according to Trueta had beneficial effects upon wounds.” With Berenblum (who later moved to the Weizmann Institute), she published papers on carcinogenic constituents of coal tar in 1943 and 1947.

In 1945 she moved from Oxford to the chemistry department at the University of Glasgow, where she remained until 1951, working with leading British specialists, including Ernest Laurence Kennaway, on aromatic organic chemicals that caused cancer.

In 1950 Schoental was awarded the D.Sc. She then joined the cancer research department at Beatson Memorial Hospital in Glasgow. Her studies included a spell at the oncology department of the Chicago Medical School. In the mid-1950s she joined the Medical Research Council (MRC) Toxicology Research Unit, Carshalton, Surrey, where she remained until September 1971.

During 1960 she was at the chemistry laboratory of CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization) in Australia; and in early 1961 in Colombo (Ceylon/Sri Lanka) on the return journey from Australia. The study of toxic natural products took Schoental to many parts of the world, particularly African countries. She visited Ethiopia and East Africa (Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya) in 1970, mainly in the search for plants used as herbal medicines and foods, in order to investigate the role of hepatotoxic plants in liver disorders. In 1963 she produced in experimental animals liver diseases comparable to those encountered in humans.

In 1971 she joined the department of pathology at the Royal Veterinary College, University College, London, as a visiting worker, initially without research funds. Here she continued research into pyrrolidizine alkaloids and nitroso compounds. In correspondence with Schoental, Berenblum suggested that her constant travels prevented her from gaining a tenured academic post.

Contributions to Cancer Research

Her research involved, successively, identification and syntheses of a number of metabolites of carcinogenic and related polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); simulation in vitro of biological oxidations of PAHs; isolation of carcinogens from shale oil and coal tar; and, from the 1960s, studies on the carcinogenic action of certain pyrrolizidine (Senecio) alkaloids and their ability to induce chronic lesions and tumors in the liver, pancreas, etc., and of diazomethane and certain nitroso compounds. Around 1970 she investigated human nasal tumors, particularly in woodworkers. Her plant studies included hepatotoxic plants in Ethiopia. Schoental’s assignments at the MRC included investigating an outbreak of poisoning known as “Epping Jaundice.” The cause was contamination of bread during transit by the epoxy resin hardener 4,4’-diaminodiphenylmethane. The results were published in Nature (1968), as was much of her other research, which could also be found in British Journal of Cancer, Cancer Research and other leading academic journals. She was a Member of Council of the Royal Society of Medicine, Section of Oncology, 1979–1982. By 1991, she had published over two hundred and seventy-five papers.

Schoental never married. According to her niece Marion Camrass, “She had not the time nor the inclination.” She showed great interest in her Jewish background and in Israel, which she visited in connection with her work. Her hobby was applying scientific theories to an understanding of catastrophic events, including those mentioned in the Bible, that might, for example, have been caused by toxic food contamination, or changing climatic conditions. She died of a sudden heart attack on January 29, 1995 and was buried in Jerusalem.

Selected Works

With Berenblum, she published on the carcinogenecity of 3,4-benzo(a)pyrene, including in Cancer Research.

“Carcinogenesis by Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and by Certain Other Carcinogens.” In Polycyclic Hydrocarbons, edited by Erich Clar, vol. 1, 133–160. London: Academic Press, 1964.

“Fusarial Mycotoxins and Cancer.” In Chemical Carcinogens, second edition, edited by Charles E. Searle, vol. 2, 1137–1169. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, 1984.

Schoental, Regina, and T. A. Connors, eds. “Mycotoxins in Food.” Dietary Influences on Cancer: Traditional and Modern. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1981.

The World Who’s Who of Women. Cambridge, United Kingdom: A & C Black, 1998.

Weinhouse, Sidney. “Cover Legend.” Cancer Research 51, no. 17 (September 1, 1991).

Schoental, Regina. “Coming to England.” The Biochemist (April/May 1992): 16–17.