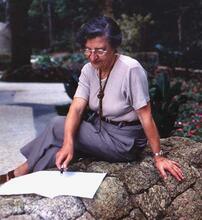

Bertha Schaefer

Born in a small town in Mississippi in 1895, Bertha Schaefer redefined the art and design scene in New York City. An interior designer by profession, Schaefer broadened the definition of interior decorator to designer, innovator, and pioneer in integrating fine arts and architecture with interior design. Schaefer founded and ran two businesses in New York City, an interior design firm and an art gallery. Her exhibitions showcased definitive art of the postwar period, paralleling that of European art movements of the 1940s. Schaefer designed for the Singer and Sons Furniture Company for over a decade. Her professional accomplishments and academic contributions garnered her significant praise and attention in the world of art and design, winning awards from institutions like the Museum of Modern Art.

By profession, Bertha Schaefer was an interior decorator, but she broadened the definition of decorator to designer, innovator, and pioneer in integrating fine arts and architecture with interior design. In the 1940s, she challenged architects who were rethinking the traditional home to translate two-dimensional design into three dimensions and to work collaboratively with interior designers, craftspeople, and fine artists in developing a comprehensive plan for postwar, contemporary living.

Early Career & Art Gallery

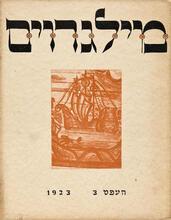

Bertha Schaefer was born in Yazoo City, Mississippi, in 1895. She, her parents, Emil and Julia (Marx) Schaefer, and her sister lived in a house designed by her father that was “untraditional” in construction and, unfortunately, poorly suited to the southern climate. Schaefer obtained a B.A. from Mississippi State College for Women and a diploma in interior decorating from the Parsons School of Design. In New York City, she opened two businesses, Bertha Schaefer, Interiors (1924) and the Bertha Schaefer Gallery of Contemporary Art (1944). Her firm and gallery featured American and European painting and sculpture, and launched the careers of many artists and designers. She was both owner and principal of the firm and gallery until her death. She masterminded a series of exhibitions called “The Modern House Comes Alive” (1947–1948), which presented what she considered to be the American parallel to the European modern arts and crafts movement, especially Germany’s Bauhaus school. The exhibitions focused on economical designs that possessed craftsmanship as well as beauty and were suited to the postwar era in which the ready availability of labor and materials would facilitate mass production. In particular, Schaefer promoted functional and economical lighting fixtures. As early as 1939, she was using decorative interior fluorescent lighting.

Interior Design

Her firm’s work included interior and furniture design for private homes, apartments, hotel lobbies, and restaurants. Other projects ranged from creating a model bathroom for General Electric (1954) to designing the interior of a new Temple Washington Hebrew Congregation (1954).

Schaefer’s innovative interiors and furniture designs caught the attention of Joe Singer of M. Singer and Sons Furniture Company in New York City. Singer appreciated Schaefer’s unique ability to marry the fine arts with the commercial arts, both in her furniture design and in her gallery. In a week-long trade show, twenty-one pieces of furniture from Italy and fifteen pieces by Bertha Schaefer debuted in an impressive showroom designed by Schaefer and Richard Kelly, an accomplished lighting designer. Schaefer continued to design furniture for Singer from 1950 to 1961.

Awards & Accomplishments

Schaefer’s professional accomplishments and academic contributions brought her invitations to participate in many round-table discussions and design juries sponsored by museums and universities. She won design awards from the Museum of Modern Art (1952) and the Decorators Club of New York (1959), the latter an organization for which she served two terms as president (1947–1948 and 1955–1957). She was also a member of the American Institute of Decorators, the Home Lighting Forum, the Illuminating Engineers Society, the Architectural League of New York, the American Federation of the Arts, and the Art Dealers Association of America.

Schaefer recognized the impact that modern imagination, technology, and industrial means of production would have on the creation of living and working environments. “These were the new areas for living, the reports of which had so quickened our imaginations, that were to expand our lives while simplifying our chores,” she explained in an article in Crafts Horizon magazine. Her constant alertness to new ideas and her professional contributions made a significant impact on the history of postwar American living, architecture, and design.

Bertha Schaefer died on May 24, 1971.

“Across the Seas of Collaboration for the New Singer Collection.” Interiors 110, December 1951: 120–129.

“Bertha Schaefer, A.I.D., Respects an Assemblage of Abstract Art in a Softly Lighted Living Room.” Interiors 119, August 1959: 81.

“Bertha Schaefer’s Lobby for an Apartment House.” Interiors 111, April 1952: 104–105.

“Bertha Schaefer Wins Award.” Interiors 118, June 1959: 20.

“Case of Ambidexterity.” Interiors 116 (December 1956): 118–121;

“Focalite.” New York Times, February 4, 1945, sec. 6, p. 12:5.

“Integrating the Arts: Newark.” Interiors 114, June 1955: 20.

Madison, Mary. “Decorator Favors Buying Paintings First and Building Color Scheme Around Them.” New York Times, September 30, 1944, 18:3.

“Modern House Comes Alive.” Crafts Horizon 13, September 1953: 30–33.

Obituary. Crafts Horizon 31, August 1971: 4.

“Bertha Schaefer, an Art Dealer And Interior Designer, 76, Dies.” New York Times, May 26, 1971, 46:.

“Portraits.” Interiors 114 (May 1955): 100+.

Roche, Mary. “A Lift From Lighting.” New York Times, January 14, 1945, sec. 6, p. 28:2.

Roche, Mary. “New Ideas and Inventions.” New York Times, June 8, 1947, sec. 6, p. 39:1.

“Trials of Jurying.” Crafts Horizon 16, March 1956: 30–35.

Who’s Who of American Women, 1958–1971.

WWWIA, 5.