Elaine Lustig Cohen

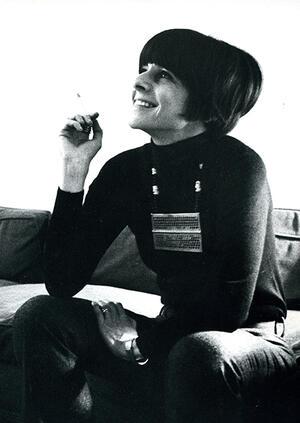

Elaine Lustig Cohen in her New York City home, 1966. Photo by Ugo Mulas, courtesy of Elaine Lustig Cohen.

With her modernist combinations of typography and photomontage, Elaine Lustig Cohen was a pioneer of graphic design and marketing. Cohen studied Bauhaus style at Tulane University before earning her degree at the University of Southern California, where she met her first husband, Alvin Lustig, a well-known avant-garde typographer and designer. Cohen honed her craft while assisting her husband, and after his death in 1955, she designed book covers for several publishers, as well as architectural signage for museums and notable buildings. Cohen’s paintings have been widely exhibited, and in 1979, she was the first woman to show at the Mary Boone Gallery. In 1972, Cohen and her second husband, theologian and writer Arthur Cohen, opened Ex Libris, a bookstore specializing in the European avant-garde.

Early Life and Education

The related fields of typography and graphic design played a vital role in the advent of modernism in early twentieth-century Europe, with many vanguard groups—better known for painting, sculpture, architecture, and manifestos—using design to test the practical application of their new modes of artistic production. The European avant-garde, imported to the United States by a wave of emigrés in the late 1930s, was embraced by a new breed of designers, eager to build upon the principles of an incipient “international style.” Elaine Lustig Cohen, with her husband, Alvin Lustig, were among the most prominent graphic designers to adopt these advanced aesthetic concepts for use in the American market.

Cohen was born on March 6, 1927, in Jersey City, New Jersey, to Elisabeth (Loeb) and Herman Firstenberg. She decided to study art at the H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College of Tulane University after learning that one of the instructors at that school had trained under the Hungarian Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy. This early interest in what became known as “International Constructivism” stayed with her, informing both her painting practice and her daily occupation. She remained in Louisiana for two years before transferring to the University of Southern California, receiving a B.F.A. in 1948. The same year she married Alvin Lustig, and she began honing her craft in the company of her husband, long considered one of the foremost American practitioners of avant-garde typography and graphic design. Using canonical modernist devices such as sans-serif type, photomontage, and geometric planes of color, the Lustigs were able to introduce high modernist design principles into the traditionally conservative American graphic vernacular.

Design Career and Later Work

After her first husband’s premature death in 1955, Cohen continued to work as a major designer for Meridien and New Directions Books in New York throughout the late 1950s. She was also a pioneer in the field of architectural signage, working on such important modernist structures as Eliel and Eero Saarinen’s General Motors Technical Institute in Warren, Michigan, of 1955; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson’s Seagram Building in New York of 1958; and interiors for the then little-known Richard Meier. Continuing her early training in the fine arts, she continued to paint—following the abstract constructivist party line—and has exhibited widely, most notably in 1979 as the first woman to show at the now-legendary Mary Boone Gallery. A retrospective of her paintings and photomontages was mounted at the prominent Manhattan gallery Exit Art in 1985.

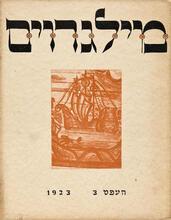

In 1972, Cohen established Ex Libris—a Manhattan bookstore concentrating on rare printed materials of the European avant-garde—with the novelist and theologian Arthur Cohen (d. 1986), whom she had married in 1956. Her work is amply represented in the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York, where a major retrospective of her graphic work was held in 1995.

Cohen, Elaine Lustig. Jan Tschichold: A Life in Typography, with Ruari McLean (1997).

Cohen, Elaine Lustig. Letters from the Avant-Garde: Modern Graphic Design, with Ellen Lupton (1996).

Blueprint (March 1995): 40–41.

Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum Magazine 2, no. 1 (Winter 1995): 8–10.

Metropolis (March 1995): 95.

New York (February 27, 1995): 140.