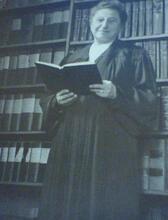

Joan Mavis Rosanove

Joan Rosanove was not the first woman to qualify as a lawyer in the Australian state of Victoria, but she was the first woman in Victoria to work specifically as a courtroom lawyer. Flamboyant and feisty, she was an outspoken champion of women's rights and battled, with grace and characteristic good humor, the sexist attitudes that inevitably laid obstacles across her path. As a pioneer “woman lawyer,” and one, moreover, who used not only her sharp intellect but her innate wit to advantage in court, she fascinated journalists, and was often featured in the press. She was buoyed throughout her career by the support of her husband, a well-known medical specialist. Her elder daughter, and in due course that daughter's son, followed her into the legal profession.

Family and education

Joan Rosanove, a trail blazing Australian lawyer, was born on May 11, 1896, in Ballarat, Victoria, and raised there. She was one of seven surviving children of lawyer Mark Lazarus and lawyer’s daughter Ruby (Braham) Lazarus. Mark and Ruby were married in their native Melbourne with Jewish rites; this seems worth stating, since at least one contemporary account mistakes them as Jews by ethnicity only. In Ballarat Joan attended the Loreto Convent, where the town’s significant upwardly mobile Irish population tended to send their daughters, and afterwards another local school, Clarendon Presbyterian Ladies’ College. Sending their children to good private schools run by Christian denominations was commonplace among those Jews who could afford the fees. Australia’s Jewish population was too small, and too integrationist in attitude, to maintain day schools of its own.

From a family of lawyers on both sides

In Australia, as in other Commonwealth countries and in Britain itself, attorneys generally practice as either barristers (courtroom lawyers) or solicitors (lawyers who work from offices and when applicable “brief” barristers to appear on behalf of clients); Joan’s father, relatively unusual in practicing as both, was known as an “amalgam.” She was not the first woman admitted to legal practice in the state of Victoria, the first having been admitted in 1905 following the enactment of enabling legislation. But she would become the first to practice exclusively as a barrister. The press observed early in her career that it would be “strange” if she had not opted for a career in law: “Her father is a lawyer; her brother is a lawyer; her grandfather and her great-grandfather were lawyers; her mother has three brothers, all barristers, and her father’s only brother is a barrister” (Telegraph, Brisbane, January 3, 1931, 13). She herself claimed that she had no childhood plans to become a lawyer and had only fortuitously taken Latin, necessary for the study of law, at school because she was infatuated with the Latin teacher. Her zest for the profession was kindled in her teens, when she helped with clerical tasks in her father's office and watched him in the courtroom.

Perhaps fearing a frustrating future for her owing to sexist prejudice, Rosanove’s father initially tried to dissuade her from following him into the male-dominated profession, but upon realizing how determined she was he relented, accepting her as his “articled clerk.” He had premises and clients in both Ballarat and Melbourne, and consequently Joan gained “amalgam” experience in both places, travelling by rail (a three-hour journey each way) between them. She endured many a long day, reaching home in Ballarat in the evening for a quick supper and sometimes interviewing clients for hours afterwards. She graduated in law from the University of Melbourne in 1917. In order that male law students who were returning from service in the First World War might complete their degrees and be admitted at the same time as she, her formal admittance to the legal profession was delayed until mid-1919.

Early Career

On first becoming a lawyer, Rosanove practiced as an amalgam, all of her briefs at that stage coming from her father. Her first case, which she won, involved defending a man who neglected his children, and in consequence of the case changes to the existing relevant legislation were deemed necessary and eventually incorporated into the state’s Child Welfare Act (1923). Then, early in 1920, when standing in as defense counsel for her father, who was busy with a simultaneous trial in Ballarat, she made headlines with her fearless exacting interrogation at a Melbourne trial of no less a witness than Australian prime minister Billy Hughes, who had clearly not expected it.

In 1920 Joan married a young Jewish physician, future prominent dermatologist Emmanuel (Mannie) Rosanove, with whom she soon moved to Tocumwal, New South Wales, where he set up in medical practice. There, in 1922, her daughter Margaret (Peg) was born. But Joan felt isolated and missed her profession. Luckily, in 1923 Mannie relocated his medical practice to Melbourne.

Victoria's first female barrister

On September 10, 1923, Joan signed the Victorian Bar roll, the first woman in the state ever to do so. However, owing to male prejudice, she had to rely on her father to send her clients. In 1925, she left the Bar in order to practise as an amalgam, concentrating on criminal and divorce cases. During the year 1932–1933, she and Mannie spent time in Canada, the United States, and Britain, where her daughter Judith was born.

In 1934, Egon Kisch (1885-1948), a Prague-born Paris-based Communist journalist of Jewish parentage, arrived at Fremantle, Western Australia, by ship en route to attend an anti-war congress in Melbourne under the auspices of the Movement Against War and Fascism. He was officially refused permission to disembark, owing to his Communist sympathies. When the ship arrived at Melbourne, Joan, in a blaze of publicity, became his legal representative. Under the terms of the federal Immigration Act of 1901, arriving foreigners could be given a dictation test in any of a number of approved European languages to test their suitability for disembarkation and possible settlement in Australia; deliberately in order to keep Kisch out, he was tested in Scottish Gaelic, and inevitably failed.

Rosanove’s specialty career in the area of family law thrived. Interviewed for the Melbourne Herald (November 8, 1948), she estimated that she was handling one-eighth of all divorce cases in Victoria. She strongly advocated the replacement of individual state divorce laws by federal legislation covering the whole of Australia.

Grappling with male prejudice

Short in stature, photogenic, and known for her ready wit, stylish wardrobe, and long cigarette holder, Rosanove did not hesitate to mingle her pugnacious and penetrating courtroom style with recourse to charm and flirtatiousness in her attempts to influence judges and sway juries. Indeed, although she advocated the right of Australian women to sit on juries, as they did in Britain (something not achieved in Victoria until 1975), she admitted that she preferred to appear for clients in front of all-male juries because, in her observations of British courtrooms, men were more sympathetic to female defendants than were women. But much of the chivalry she received from judges and male barristers masked a patronizing attitude toward her as a woman. When, fairly early in her adversarial career, she considered it opportune to acquire a room at Melbourne’s prime barristers' premises, Selborne Chambers, she was thwarted by male indignation, and, much later, she succeeded in locating there only because a sympathetic male barrister with much less experience and seniority in the profession made her his assistant and then moved interstate. In 1950 she turned up at an official reception by the incoming governor of Victoria at the state parliament building only to be compelled to leave because only male barristers were deemed eligible (Melbourne Herald, June 8, 1950). Between 1954 and 1965 she made several applications to “take silk”—to become a senior member of the Bar, known as a “Queen’s Counsel” (QC)—but was rejected owing to sexist obduracy. She was finally made a QC in Victoria on November 16, 1965. The delay had thwarted her hopes of becoming the first female QC in Australia, for in 1962 the future Dame Roma Mitchell who, being younger, had begun her law career later than Joan, was appointed a QC in South Australia.

Joan died of a heart attack on April 8, 1974, at the Melbourne seaside suburb of Frankston, where she had passed a happy and active retirement, and was cremated.

Carter, Isabel. Woman in a Wig: Joan Rosanove QC. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press, 1970.

De Vries, Susanna. The Complete Book of Great Australian Women. Sydney: HarperCollins, 2003, 293-317.

Falk, Barbara. “Rosanove, Joan Mavis.” In Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 16, Carlton South: Melbourne University Press, 2002 (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rosanove-joan-mavis-11560; accessed August 21, 2019).

Kisch, Egon Erwin. Australian Landfall. London: Martin Secker & Warburg, 1937.

National Library of Australia, MS2414, Papers of Joan Mavis Rosanove, 1923-1955.

Ryan, Siobhan. “Joan Rosanove QC.” Victorian Bar News, Winter 2015, 90-97.

Smith, Lauren “An Accidental Lawyer,” https://law.unimelb.edu.au/alumni/mls-news/issue-20-november-2018/an-ac… (accessed 18 December 2019).