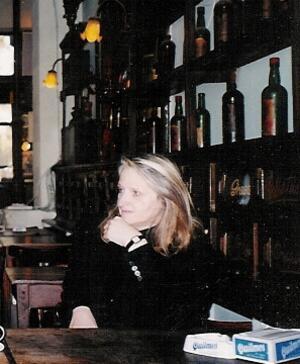

Diana Raznovich

Novelist and Playwright Diana Raznovich, August 1998.

Photo by Erna Pfeiffer. From Wikimedia Commons.

Diana Raznovich was born in Buenos Aires and began her literary career at the age of 16 with her first published volume of poetry. A playwright, poet, novelist, and cartoonist, she has lived in Spain since the early 1990s. Her works often focus on feminist and Jewish themes. In addition to her prolific dramatizations, stories, and novels, she has been a correspondent for major newspapers in Argentina with her comic strips with emphasis on feminist issues. Many of her plays have been produced in Argentina, Spain, the US and Germany, and translated into English and German.

Family & Education

Diana Raznovich was born in Buenos Aires on May 12, 1945. Her paternal grandparents emigrated to Argentina from tsarist Russia in 1905, while her maternal forebears arrived from Vienna in 1922. Her father, Marcos (1916–1973), was a pediatrician; her mother, Bertha Luisa Schrager (1916–2004), was a dentist. They married in April 1944 and were, in their daughter’s words, “an odd and loving couple.” They had two sons and a daughter, Diana, and they gave them a Jewish and a general education.

An avid reader since childhood, Raznovich was indelibly impressed by Alice in Wonderland. Beginning at the age of four, she wrote poetry and played the piano. She began her literary career at the age of sixteen with “Tiempo de amar” (A Time to Love), a volume she defines as “nihilistic” poetry. In college, she studied literature.

Spain & Argentina

In 1976, during the military dictatorship in Argentina, Raznovich immigrated to Spain, carrying only a few personal belongings. By then she had already staged her first plays in Argentina: “Buscapiés” (Black-snake Firecracker”), which won the “Premio Municipal Autora,” and “Plaza hay una sola” (There is only one Plaza), an outdoor show at the Plaza Roberto Arlt. She remained in Spain until 1981, teaching drama at the Centro de Estudios Teatrales in Madrid.

Raznovich returned to Argentina to participate in the dramatists’ collective festival of Teatro Abierto (Open Theater), staging a cycle of one-act plays in defiance of the military regime. Her play “El Desconcierto” (Bewilderment), presented during this cycle, was also produced in London two years later. During the 1990s Raznovich was on the board of directors of Argentores, the Society of Argentine Authors, and served as President of its Theatre Commission from 1986 to 1989. Since her move back to Spain in 1993, this time to settle permanently, she has travelled frequently throughout Europe as her plays were performed in Italy, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, England and Switzerland. She holds both Argentine and Spanish citizenship and divides her time between Argentina and Spain. Her plays, widely produced in America and in Europe, have been translated into English and German.

Feminist & Jewish Themes

Although Raznovich is chiefly a dramatist, she has also worked as a television screen-writer (Bárbara Narváez, 1983), a graphic cartoonist, and a novelist. In 1986 she participated in Mitominas, a multi-disciplinary event considered the first feminist exhibit at the Centro Cultural Recoleta, of Buenos Aires. Her novel Para que se cumplan todos tus deseos (May All Your Wishes Come True, 1994) shows the strong influence of magical realism. In it, a wizard capable of creating vast riches is kidnapped by greedy criminals, whereupon he loses his gift. The novel is a reflection on powerful talent, which evaporates when exploited. Her second novel, Mater erótica (Erotic Mother, 1991), represents the fall of Communism in Europe as a shaking off of sexual and political taboos.

Throughout her prolific career Raznovich has explored the female role in its multiple manifestations. Her writings invite a kaleidoscopic reading. They are poetic, rather than ideological or anecdotal, and always iconoclastic. Influenced by family history and what she calls her “Hebrew roots,” Raznovich immerses herself fully in Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah and The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah, in the Jewish tradition. Her Jewish spirit prevails in her inclination towards metaphysical reasoning and universal metaphors, as well as in the role humor plays in dealing with relationships, sexuality, and stereotypes. By employing a profusion of clichés, she poses serious and original questions. She often sets her plays in surrealistic, absurd milieus that bring to mind images from Franz Kafka and Samuel Beckett.

Raznovich’s female characters strive to escape from a suffocating environment of confinement. In “Desconcierto” (1981), which also translates as “Out of concert,” she uses a series of effective strategies to question the masculine gaze and its normative role over the female body, and she parodies feminine archetypes in a patriarchal society. The decision of a pianist to tell the audience her life story rather than perform her concert on a piano that emits no sound acquires added significance in the context of the censorship imposed by the Argentinean military regime on its population.

Raznovich’s most acclaimed play, “Jardín de otoño” (Autumn Garden, 1983), can be regarded as a criticism of mass culture projected through the media, as an exposition of class conflicts, or even as a fantasy of heterosexual love that conceals the fear of homosexuality. The play is about two spinsters who naively devise a plot to kidnap a soap-opera star in order to save him from a fictional danger. Their rather pathetic longing for their hero permits them to idealize him as long as he is unreachable. “Jardín de otoño” also reveals manifestations of Jewish consciousness: The longings of the protagonists are suggestive of the age-long futile dreams of redemption of the author’s Jewish ancestors.

The scenery of “Objetos perdidos” (Lost Belongings, 1988) is recognizable to every wanderer – suitcases packed and ready for any eventuality. The strong metaphors of this monologue bestow a sense of urgency that pervades all of Raznovich’s dramas. This metaphor stands for the exiles who escaped the military dictatorship in Argentina and for the “desaparecidos” (“disappeared”), who were taken by force and never returned alive. In this play, Casalia Beltron, totally lost amidst her own luggage, opens each suitcase to reveal loose remnants of her past life. In the author’s mind “Lost Belongings,” a notice commonly displayed at trains stations and airports, is reminiscent of the anguish and confusion Raznovich herself felt upon leaving her country and having to decide what items were essential to take along. With no one to welcome Casalia except for a loudspeaker warning her to be careful, the play’s atmosphere is that of a nightmare that persists even after Casalia wakes up. Enveloped by suitcases, her last recourse is to get into a suitcase herself. Images of lost and found objects increase her paranoia. No matter what Casalia says or does, she fears being always regarded with suspicion.

From the Jewish perspective, the process of transplantation evokes what the playwright imagines her ancestors must have suffered before each exile. The crowded landscape of luggage that fills the stage stands for the home of the Jew, surrounded by the perpetual presence of suitcases, conveying the idea that Casalia will have to move on to unknown places for indefinite periods of time. When she hesitantly opens some of the cases, what she finds in them are human bones belonging to her loved ones. Her memories then become unbearably real.

Other Themes

Among Raznovich’s other plays, “Casa matriz” (Matrix House, 1988) is a parody of consumerism, both social and individual, that trades on human emotions rather than catering to real needs. In this comedy, from the “menu” of possibilities an agency has to offer, a daughter may rent a substitute mother designed to act like a real one. In “La madre judía posmoderna” (The Postmodern Mother, 1993, unpublished), a feminist scholar has to attend psychoanalytic sessions with her forty-year-old son, who refuses to release her from motherly duties. “De atrás para adelante" (Rear Entry, 1993), a parody of a Jewish father with a transsexual son, is a reflection on the prejudices of a traditional family toward a child who is different. “De la cintura para abajo” (To the Waist Down, 1999) satirizes the boredom of a bourgeois couple who engage the services of an unemployed torturer after democracy is restored, to act as their sado-masochistic sexologist and help them solve their marital problems.

Over the past decade in Spain, Raznovich has continued writing, teaching, producing new plays, and working as a graphic humorist with Sopa de Lunares (2009), Mujeres Pluscuamperfectas (2009), and Divinas y Chamuscadas (2011).

Razonovich received the Guggenheim Award in 1993. In 2012 she participated in Barcelona’s Festival Magdalena with “El santuario Estresado” (The Stressed Out Sanctuary) in Barcelona, and in 2016 she was awarded the “Premio de la Federación de Mujeres Progresistas” (Federation of Progressive Women Award) in Madrid. Between 2012 and 2018, she published graphic art contributions in the weekly edition of Clarín, a Buenos Aires newspaper.

Selected Works

Tiempo de amar y otros poemas. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Nuevo Día, 1963.

Mitomimas: A multi-disciplinary event. Buenos Aires,1986.

https//es.wikipedia.org/wiki/DianaRaznovich

Jardín de otoño. Dirección de Bilbliotecas, Buenos Aires: 1985.

Cables pelados. Ediciones Lúdicas, Buenos Aires: 1987.

Para que se cumplan todos tus deseos. Madrid: Exadra 19.

“El Desconcierto,” in Teatro abierto. Buenos Aires: 1992, 315–322.

Mater erótica. RobinBook, Barcelona: 1992.

Casa Matriz in Holy Terrors: Latin American Women Perform, 1988.

scalar.usc.edu/nehvectors/taylor/casa-matriz-script

Paradise y otros monólogos. Nuevo Teatro. Buenos Aires: 1994.

Teatro completo de Diana Raznovich. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Dédalos, 1994

Objetos perdidos (Lost Belongings). In Contemporary Argentine Jewish Drama: A Critical Anthology in Translation, edited by Nora Glickman and Gloria Waldman. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press,1996.

Defiant Acts/Actos desafiantes-- Four Plays/ Cuatro Obras. Edited by Diana Taylor and Victoria Martínez, Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2002.

Taylor, Diana, and Roselyn Costantino, eds. Holy Terrors: Latin American Women Perform: A Manifesto of Feminine Humor. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Olimpia o la pasión de existir, 2007, Ed. Hotel Papel, 2009.

De atrás para adelante in Defiant Acts, edited by Diana Taylor & Victoria Martinez. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2002.

De la cintura para abajo, in Dramaturgas en la escena del mundo: Mercedez Farriol, Nora Glickman and Diana Raznovich. Edited by Diana Taylor. Buenos Aires: Editorial Nueva Generación, 2004.

Sopa de Lunares (Graphic novel) Ed. Hotel Papel, 2009.

Mujeres Pluscuamperfectas (Graphic novel) Ed. Hotel Papel, 2009.

Divinas y Chamuscadas (Graphic novel) Ed. Hotel Papel, 2011.

Olimpia o la pasión de existir, with Margarita Borja, Colección Sender, UJI. 2016.

Agosín Marjorie. “Paradojas y mitos judaicos en dos obras de Diana Raznovich.” Noaj 9 (1993): 83–87.

Ibañez Quintana, Nuria. “El Desconcierto de Diana Raznovich: imagen y palabra el cuerpo femenino como lugar de resistencia.” Telón de Fondo, 12, VI, 2010.

Ibañez Quintana, Nuria. Funciones de género: Mito, historia y arquetipo en tres dramaturgas iberoamericanas: Lourdes Ortiz, Sabina Berman y Diana Raznovich. Peter Lang Inc., 2015.

Larson, Catherine, Games and Play in the Theater of Spanish American Women. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, Lewisburgh, 2004.

Magnarelli, Sharon. “Simulacra and Commodification in Diana Raznovich's Casa Matriz (or Whose Life Is This Anyway?).” Letras Femeninas 32.1 (Summer 2006):169-87.

Martínez, Marta. “Tres nuevas dramaturgas argentinas: Marta Mahieu, Hebe Uhart and Diana Raznovich.” Latin American Theatre Review 13.2 (1980): 39–45.

Taylor, Diana. “What is Diana Raznovich Laughing At?” Holy Terrors: Latin American Women Perform. Edited by Diana Taylor and Roselyn Costantino. Durham: Duke UP, 2003, 3-92.

Weinstein, Ana and Miriam Nasatsky, eds. Escritores judeo-argentinos. Bibliografía. 1900–1987. Buenos Aires: 1994, 103–10.