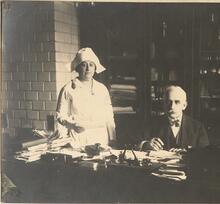

Judith Graham Pool

Judith Graham Pool.

Courtesy of Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

Physiologist Judith Graham Pool revolutionized the treatment of hemophilia by isolating factor VIII and creating a concentrate made from blood plasma that could be frozen, stored, and used by hemophiliacs in their own homes. Pool began a research fellowship at Stanford in 1953 and published her first paper on hemophilia the following year. By 1972 she was a full professor at Stanford and a member of the advisory committees of the National Institutes of Health and the National Hemophilia Foundation. As co-president of the Association of Women in Science and founding chair of Professional Women of Stanford University Medical Center, she pushed to create better opportunities for women in science.

Article

Judith Graham Pool was a physiologist whose scientific discoveries revolutionized the treatment of hemophilia.

She was born in Queens, New York City, on June 1, 1919, to Nellie (Baron) Graham, a schoolteacher, and Leon Graham, a stockbroker. After graduating from Jamaica High School, she attended the University of Chicago, where she was a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Sigma Xi. In 1938, she married Ithiel de Sola Pool. Together they had two sons, Jonathan Robert (b. 1942) and Jeremy David (b. 1945). In 1946, Pool received her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago.

When the couple moved to California in 1949, Pool began both her lifelong relationship with Stanford University and her illustrious career as a research scientist. Pool started out as a research associate at Stanford Research Institute in 1950. In 1953, she joined the staff at Stanford’s School of Medicine as a research fellow, supported by a Bank of America-Giannini Foundation grant for hemophilia research. That same year, she and her husband divorced.

Pool then initiated her extensive research on blood coagulation, publishing her first paper on the topic in 1954. Working with two associates, Pool developed a method for separating the antihemophilic factor (AHF), or factor VIII, which is used for transfusion to correct the bleeding defect in hemophilia, from blood plasma. She was then able to create cryoprecipitate, a cold-insoluble protein fraction of whole blood plasma, which was available to the public in 1965. This concentrate could be made without special equipment, left in a plastic bag, and refrozen and stored up to a year, thereby allowing hemophiliacs to be treated with more ease than ever before in their homes or in any hospital or medical facility.

Her work on muscle physiology was also noteworthy. Pool developed techniques to measure the electric potential of a single muscle fiber within a membrane. These techniques are used all over the world.

Pool earned the title of senior research associate in 1956, senior scientist in 1970, and full professor in 1972, without ever going through the lower professorial ranks. The value of her contributions was widely recognized, and she was invited to lecture at numerous institutions and congresses. She was a member of the scientific advisory committees of the National Institutes of Health and the National Hemophilia Foundation, which renamed its research fellowship the Judith Graham Pool Research Fellowship in her honor.

In her later years, Pool devoted much time and effort to increasing opportunities for women in the field of science, both by publishing articles on the topic and by serving as the co-president of the Association of Women in Science and as the first chairwoman of Professional Women of Stanford University Medical Center.

Pool gave birth to one daughter Lorna (b. 1964). In 1972, she married Maurice Sokolow, professor of medicine and hematology at the University of California, San Francisco. They were divorced in 1975.

Judith Graham Pool died at age fifty-six on July 13, 1975, in Palo Alto, of a brain tumor.

Massie, Robert K., and Suzanne Massie. Journey (1975).

Obituary. NYTimes, July 15, 1975, 36:2.

NAW modern.

WWWIA 6.