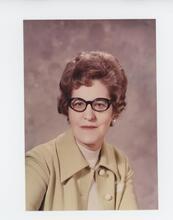

Ellen Moers

While early critics attacked Ellen Moers’s 1976 book Literary Women for its exclusive focus on women writers, her analysis of Mary Shelley and other women writers reshaped our understanding of their work. After earning her master’s, Moers began teaching at schools throughout the New York area while writing for various newspapers and periodicals. She later began publishing her academic studies, The Dandy and Two Dreisers, though it was her third book, Literary Women, that made the greatest impact on literary criticism. Moers argued that women authors had profoundly different life experiences from their male counterparts, and that those experiences created a unique literary culture—an argument that was controversial at the time but that has become the essential and obvious core of feminist literary theory.

Article

Ellen Moers credits “the new wave of feminism for pulling [her] out of the stacks” and into the material that was to become Literary Women (1976). That book, the third and last in her career, is a benchmark of feminist criticism.

Ellen Moers was born on December 9, 1928, to Robert Moers, a lawyer, and Celia Lewis (Kauffman) Moers, a teacher. Her older sister, Mary Wenig, became an attorney and a professor; her niece, a rabbi. Moers was schooled in New York City, earned her B.A. at Vassar (1948), her M.A. at Radcliffe College (1949), and her Ph.D. at Columbia University (1954). She married the writer Martin Mayer in 1949 and had two children, Thomas and James. The family expressed its Jewishness in largely secular ways. Moers taught at Hunter College, Barnard College, Brooklyn College, and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and wrote for major newspapers and periodicals. By comparison with Literary Women, The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm (1960) and Two Dreisers (1969) seem dutiful academic exercises. The Dandy shows the limits of its dissertation origins, but it also exhibits both the author’s lifelong focus on cultural and comparative literature and her mastery of French literature, which she would use to perfection in Literary Women. Her second book moves far away from the subject of the dandy to Theodore Dreiser’s novels Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy.

In her third book, Moers found her true subject. She was deeply affected by the second wave of feminism then in progress. The marriage of that new approach to her matured criticism resulted in a major work. Literary Women demonstrates that by the nineteenth century, English, American, and French women writers had a literature and a culture of their own that has become stronger in the twentieth century. Moers boldly asserts that women have particularly strong insights into issues of work, money, social justice, and the heroic.

A prime example of Moers’s critical originality is her interpretation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. That work had never been read in terms of Shelley’s gender, biography, or the female Gothic tradition. From a work that seemed to come out of nowhere, Frankenstein becomes under Moers’s approach a novel deeply tied to Shelley’s life as a teenage unwed mother who had experienced several miscarriages and infant deaths, and whose own birth resulted in the death of her mother, the feminist and novelist Mary Wollstonecraft. Death and birth become painfully intertwined in the novel; it is no accident that Shelley called Frankenstein her “hideous progeny.”

Some early reviews attacked Literary Women for its focus on women, but within a few years it became a classic work that underpins subsequent feminist literary criticism of English and American novels.

At the time of her death on August 25, 1979, Ellen Moers was working on a book about the interrelationship between British and American literary figures of the nineteenth century. Her critical approach remained comparative, cultural, and gendered.

Selected Works by Ellen Moers:

The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm (1960).

Literary Women (1976).

Two Dreisers (1969).

Howard, Maureen. “Literary Women.” NYTimes Book Review, March 7, 1976, 4–6.

Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher. “Why Not Literary People?” NYTimes, March 12, 1976, 31.

Winegarten, Renée. “Ladies of the Desk.” American Scholar 45 (Autumn 1976): 607–610.

Wood, Michael. “Heroine Addiction.” New York Review of Books, April 1, 1976, 12–13.