Miriam: Midrash and Aggadah

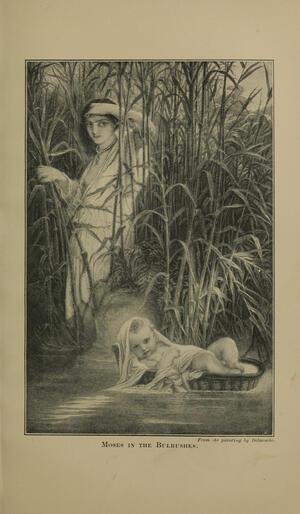

"Moses in the Bulrushes," from Lillian Louise Price, Wandering Heroes (New York: Silver, Burdett and Company, 1902), via Wikimedia Commons.

Together with Moses and Aaron, Miriam is described in the midrash as part of a family triumvirate of leaders. Although unlike her brothers she had no formal position, the Rabbis assert that she contributed greatly to the redemption of Israel from Egypt. She is mentioned as the one who prophesied the birth of Moses and his role as the deliverer who would redeem Israel from the Egyptians, a task in which she would assist him. Her reward came when she contracted leprosy and the Ark, the Divine Presence, and all Israel waiting for seven days until she was healed. Miriam acted as a leader during the wanderings in the wilderness; by her merit the Israelites were accompanied on their journeys by the well that bears her name.

Together with her brothers, Moses and Aaron, Miriam is described in the midrash as part of a family triumvirate of leaders. Although, unlike her brothers, she did not have any formal position, the Rabbis assert that she contributed greatly to the redemption of Israel from Egypt. She is mentioned as the one who prophesied the birth of Moses and his being the deliverer who would redeem Israel from the Egyptians, a task in which she would also assist him. In addition, Miriam acted as a leader during the wanderings in the wilderness; by her merit the Israelites were accompanied on their journeys by the well that bears her name: “Miriam’s Well.”

Miriam the Prophet

Miriam first appears in the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah anonymously, as the sister of Moses who stands on the riverbank (Ex. 2). She is mentioned by name in the Song at the Sea, where she is called (Ex. 15:20) “Miriam the prophet, Aaron’s sister.” The A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash learns from this verse that Miriam prophesied even before the birth of Moses, when Aaron was her only brother, and the Rabbis depict her character and her prophecies that preceded these events.

Ex. 2 describes the birth of Moses. Verse 1 begins with the marriage of Jochebed and Amram, which is immediately followed by the narrative of Moses’s birth, concealment, and rescue. This continuum actually extends over a considerable period of time, since Jochebed and Amram already had two children, Aaron and Miriam, when Moses was born (as is related in v. 6). The Torah apparently chose to focus on the birth of the deliverer of Israel and therefore disregarded his two older siblings.

The Rabbis resolved this seeming contraction of the events by explaining that Jochebed and Amram had divorced, and Ex. 2:1 details their remarriage. According to the midrash, when Amram took back Jochebed, he did so on the counsel of his daughter (BT Suspected adulteressSotah 12b). The Rabbis state that Amram was the outstanding scholar and leader of his generation. When he saw that Pharaoh had decreed that all the boys be cast into the Nile, he proclaimed: “Are we laboring in vain” [we give birth to sons who will eventually be killed], and so he divorced his wife. All Israel saw this, and in consequence they also divorced their wives.

Miriam, who was six years old at the time (or five, according to some of the sources), said: “Father, Father, your decree is harsher than that of Pharaoh. Pharaoh only decreed against the males, but you have decreed against both the males and the females [because all the Israelites withdrew from their wives, neither sons nor daughters would come into the world]. Pharaoh decreed only for this world, but you decreed both for this world and the next [a baby that was born and died as a result of Pharaoh’s decree would reach the World to Come, but an unborn child would not attain this]. It is doubtful whether the decree of the wicked Pharaoh will be fulfilled, but you are righteous, and your decree will undoubtedly be fulfilled.” Amram heeded his daughter, and returned to his wife.

Amram remarried Jochebed in a public celebration with all possible pomp and ceremony: he sat her in a palanquin, Aaron and Miriam danced before her, and the ministering angels proclaimed (Ps. 113:9): “He sets the childless woman [akeret ha-bayit] among her household as a happy mother of children.” Jochebed, who had been uprooted [nitakrah) from her home as a result of the decree of Pharaoh, would now be set among her household in joy. All Israel saw this, and they, too, remarried their wives (Mekhilta de-Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai 6 [ed. Epstein-Melamed, p. 6]; BT Sotah 12a; Pesikta Rabbati 43).

The Rabbis connect Miriam’s standing by the riverbank with her prophesying. Miriam prophesied that her mother would give birth to a son who would deliver Israel. When Moses was born and the house was filled with light, Amram rejoiced and praised Miriam because her prophecy had come to pass. However, once Moses was cast into the river, Amram charged her with making a false prediction. Therefore, Miriam stood at a distance, by the riverbank, to know whether her prophecy would be fulfilled (BT Lit. "scroll." Designation of the five scrolls of the Bible (Ruth, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The Scroll of Esther is read on Purim from a parchment scroll.Megillah 14a; Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Masekhta de-Shirah, Beshalah 10).

The Rabbis assert that Miriam was rewarded for waiting by the riverbank for a short time to learn what would befall Moses. Her reward was greater than her deeds several times over, for when she contracted a skin affliction (zara’at, commonly rendered as “leprosy"), the Ark, the Shekhinah (the Divine Presence), the Priests; descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses, who were given the right and obligation to perform the Temple services.kohanim, the Levites, and all Israel, with the clouds of glory, waited for her for seven days until she was healed (M Sotah 1:9). The Rabbis note Miriam’s speed in calling her mother Jochebed to nurse Moses, and her wisdom in concealing from the daughter of Pharaoh that she was the infant’s sister (BT Sotah 12b).

Miriam—One of the Hebrew Midwives

The Rabbis identify Miriam with Puah, one of the two Hebrew midwives (Shiphrah and Puah) who served the Israelites during the Egyptian enslavement. Why was she called “Puah”? Because she appeared (hofi’a) with good deeds for Israel. In another explanation of her name, when she went with her mother to the expectant woman, she would bleat (poah) like a sheep to the woman in labor, which acted as a stimulus and aided the woman’s delivery. Another view has her squirting (nofa’at) wine into the baby’s mouth, causing the newborn to cry out when it was thought to be stillborn (Ex. Rabbah 1:13; Eccl. Rabbah 7:3; Midrash Samuel 23:2).

Another explanation of her name relates to her behavior toward Pharaoh. When she heard the royal edict, she was insolent (hofi’ah panim) toward Pharaoh and looked down her nose at him. She told him: “Woe to you on the day of judgment, when God will come to demand punishment of you.” Pharaoh immediately became enraged at her and wanted to kill her. She was saved thanks to her mother, who mollified him and said to him: “Do you take notice of her? She is a baby, and knows nothing” (Ex. Rabbah, loc. cit.). Another explanation of her name is related to the birth of Moses. Puah (= Miriam) would cry out (poah) with divine inspiration and say: “My mother shall give birth to a son who will save Israel” (BT Sotah 11b). In another exegetical account, she was called Puah because of her insolence, which—in this depiction—was directed against her father Amram, in protest against his abstinence from his wife when Pharaoh ordered that the Israelite boys be cast into the Nile (Ex. Rabbah loc. cit.). Another etymological tradition explains that she was so named because she cried out (poah) and wept for her brother Moses when he was cast into the river (Sifrei on Numbers, 78).

In its various meanings, the name “Puah” therefore embodies two different character traits that the Rabbis find in Miriam’s personality: on the one hand, she exhibits sensitivity and tenderness: she bleats to the infant and weeps for her brother; while, on the other, she acts assertively and aggressively and is insolent both to her father and to Pharaoh.

According to the Rabbis, her reward for not heeding Pharaoh was having progeny who would be sages and kings. One of her descendants was Bezalel, who was filled with wisdom, as Ex. 31:3 attests: “I have endowed him with a divine spirit of skill [or, wisdom].” The midrash ascribes the exceeding wisdom of the tribe of Judah to Miriam’s merit (Ex. Rabbah 48:4; for the tradition that Miriam was married to Caleb). Another tradition attributes royalty to her by merit of her conduct, for King David was descended from her (Sifrei on Numbers loc. cit.; BT Sotah 11b). These traditions are exegetical expansions of the description in Ex. 1:21 of the reward that God gave the midwives: “He established households for them.”

The Song at the Sea

Miriam is first mentioned by name at the Song at the Sea (Ex. 15:20–21): “Then Miriam the prophetess, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women went out after her in dance with timbrels. And Miriam chanted for them, ‘Sing to the Lord, for He has triumphed gloriously; horse and driver He has hurled into the sea.’“ In the midrashic account, Miriam led the chanting, and she was the equivalent of them all, since she began the chanting (Pesikta Zutarta [Lekah Tov, Ex. 15:20). All the women followed her [aharekha] in dance [bi-meholot], which led the Rabbis to call her Aharhel, a name that appears in the genealogy of the tribe of Judah in I Chron. 4:8 (Ex. Rabbah 1:17).

The Rabbis praise Miriam’s great trust in God and steadfast faith, which are reflected in the very fact of Miriam’s having a timbrel in her hand. They ask: “Whence did the Israelites have timbrels for dancing in the wilderness? Rather, the righteous trusted in God, they knew that He would perform miracles and mighty acts when they would go forth from Egypt, and they prepared for themselves timbrels and dancing” (Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael loc. cit.; Pesikta Zutarta loc. cit.).

The Rabbis take note of the fact that these verses refer to Miriam as Aaron’s sister (and not as the sister of Moses) and as a prophet. They assert that Aaron acted selflessly when Miriam suffered her skin affliction, and therefore she is called “Aaron’s sister.” As regards the omission of Moses, this verse teaches that her prophecy began before Moses was born (BT Megillah 14a; Sotah 12b; Mekhilta de-Rabbi Simeon bar Yohai 15; Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael loc. cit.).

Miriam as the Leader of Israel in the Wilderness

Miriam is portrayed as an integral member of the Moses-Aaron-Miriam leadership triumvirate. In the midrash’s allegoric interpretation of the cupbearer’s dream (Gen. 40), Moses, Aaron, and Miriam are the three branches of the vine from which the people of Israel emerged and blossomed. According to another view, the three branches are the manna, the pillar of cloud, and the well (BT Hullin 92a), which are the three gifts that Israel received by merit of its three leaders. The Rabbis also compare various aspects of the death of the three.

The midrash relates that the Israelite camps set out with only Miriam in their lead (Sifrei on Deuteronomy, 275). This exposition gives expression to Miriam’s leadership in the wilderness, in the sight of all the tribes.

Miriam’s Well

The description in Num. 20 of the death of Miriam is immediately followed by the episode of the Waters of Meribah: “Miriam died there […] The community was without water” (vv. 1–2). The Rabbis learn from this juxtaposition that Miriam’s death resulted in the dearth of water; they credited to her the existence of the well that accompanied the Israelites on their wanderings in the wilderness and provided them with drinking water. The well, according to the Rabbis, was one of the things created on the eve of the Sabbath at twilight (M Avot 5:6); they depict it as a wondrous well that flowed from itself, like a rock full of holes (T Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.Sukkah 3:11). The well is portrayed in a mural in the Dura Europus synagogue (which was destroyed in the third century CE), in which we see Miriam’s Well, with streams of water issuing forth to each of the tents of the twelve tribes of Israel.

The midrash lists the well among the three gifts that were given to Israel by merit of their leaders. The manna was given on account of Moses, the pillar of cloud, by merit of Aaron, and the well, by merit of Miriam. The well that then reappeared by merit of Moses is the one mentioned in the song of the well (Num. 21). All three gifts—the well, the manna and the cloud—finally disappeared upon the death of Moses (Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Beshalah 5; T Sotah 11:1; BT Taanit 9a; Num. Rabbah 1:2). According to the Statements that are not Scripturally dependent and that pertain to ethics, traditions and actions of the Rabbis; the non-legal (non-halakhic) material of the Talmud.aggadah, this well continues to issue within the sea (BT SabbathShabbat 35a), or the Sea of Galilee (JT Kilayim 9:3, 32 [c]; the latter source even provides the geographic location of the well within the Sea of Galilee).

In these exegeses, Miriam is a central source of vitality; they portray her as a foremost leader, who cares for Israel’s needs in the wilderness.

The Cushite Woman and the Skin Affliction of Miriam

The Rabbis devote much attention to Miriam’s skin affliction. They relate to the content of her statements, the connection between her criticism of the Cushite woman and what she says about the special standing enjoyed by Moses, and her motivation for speaking in this manner. They also examine why the Torah is particularly concerned with Miriam’s punishment, and not that of Aaron, Moses’s prayer that Miriam be healed, and the stay by the entire people until her recovery.

Num. 12:1 attests: “Miriam and Aaron spoke [va-tedaber] against Moses because of the Cushite woman he had married.” The Rabbis take special note of the feminine singular form of the verb, from which they deduce that Miriam spoke first, despite Aaron’s higher standing as a prophet, because she perceived a great necessity for doing so (Sifrei on Numbers, 99).

The topic of the Cushite woman raised considerable difficulties for the Rabbis, since the Torah does not state that Moses took another wife, nor does it speak of additional children that she bore him. Furthermore, it would have been objectionable for Moses to have taken an additional wife while Zipporah was waiting for him to join her in her father’s house.

The Rabbis maintain that the Cushite woman was Zipporah and that the word “Cushite” describes her fine qualities (her beauty and her actions). If so, then what flaw did Miriam and Aaron find in her when they spoke against Moses (Num. 12)? The Rabbis assert that Miriam and Aaron talked about Moses having withdrawn from his wife. The midrash admits that Moses abstained from intercourse with his wife from the time of the Giving of the Torah, but this was at God’s behest. Before the Revelation, God ordered Moses to sanctify the people, bidding them (Ex. 19:15): “Be ready for the third day: do not go near a woman.” All Israel withdrew from their wives and Moses withdrew from his wife. After the Giving of the Torah, God instructed Moses (Deut. 5:26–27): “Go, say to them, ‘Return to your tents.’ But you remain here with Me”—Israel shall return to their wives, but you shall not return to marital relations (Tanhuma, Zav 13).

Since modesty is appropriate for the relations between a man and his wife, how did Miriam learn of Moses’s abstinence? According to one tradition, Miriam saw that Zipporah no longer adorned herself with women’s jewelry, and she asked her: “Why have you stopped wearing women’s ornaments?” Zipporah answered: “Your brother no longer cares about this.” Thus Miriam learned that Moses had abstained from intercourse (Sifrei on Numbers loc. cit.).

In another exposition, Miriam is next to Zipporah when Moses was told (Num. 11:27) that “Eldad and Medad are acting the prophet in the camp!” Zipporah’s reaction to this report was: “Woe to their wives. They will be prophets, and they will withdraw from their wives, as my husband withdrew from me.” Thus, Miriam learned that Moses abstained from relations with Zipporah, and she told this to Aaron (Tanhuma loc. cit.).

In yet a third exegetical expansion, Zipporah began the conversation with Miriam, who told this to Aaron, who in turn added to what she had said and the two discussed the matter. Miriam learned of this after the appointment of the seventy elders (Num. 11). Following their appointment, all Israel kindled lamps and engaged in celebrations, rejoicing at the elders having attained their exalted status. When Miriam saw the lamps, she exclaimed: “Happy are these and happy are their wives!” Zipporah corrected her: “Do not say, happy are their wives, rather, woe to their wives. From the day that God spoke to Moses your brother, he has not had relations with me.”

Miriam immediately went to Aaron and the two discussed the matter. They said: “Moses is haughty. The Lord has already spoken with many prophets, and with us as well, but we did not abstain from our wives as Moses has done” (Sifrei Zuta 12:1). The two latter midrashim are based on the juxtaposition of the appointment of the seventy elders and the prophesying of Eldad and Medad (Num. 11) with the conversation between Miriam and Aaron (chap. 12). These expositions portray the female solidarity between Zipporah and Miriam, with the latter offering a sympathetic ear and even trying to help her fellow woman.

The manner in which the Rabbis portray Miriam’s concern for felicitous marital relations between Moses and Zipporah somewhat parallels their descriptions of her concern for the proper marital life of Amram and Jochebed. In both instances, out of concern for procreation, she criticizes the one who withdrew from his wife. The Rabbis censure Miriam for not understanding that Moses’s behavior was a special case.

In its description of the conversation between Aaron and Miriam, the Torah mainly emphasizes the latter’s role: “Miriam and Aaron spoke.” In the description of the punishment, the Torah speaks only of the skin affliction of Miriam, although both were rebuked by God. In one Rabbinic tradition, Aaron also received punishment, but to a lesser degree, since Miriam initiated the conversation, took the leading role in it and even “was active in the matter” (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan, version A, chap. 9; Sifrei Zuta 12:9). In order to explain why only Miriam was punished, the Rabbis present a parable of a thief in a vineyard who picks grapes and gives them to his fellow outside the vineyard. The vineyard owner catches and punishes only the one actually within his vineyard.

Thus, both Miriam and Aaron shared in this transgression, but Miriam was active, while Aaron only received her words (Sifrei Zuta loc. cit.). Another tradition concedes that Aaron also deserved to be punished, but the cloak of the High Priest protected him, since it atones for slander (Sifrei Zuta loc. cit.). Yet another tradition claims that Aaron did not suffer from this affliction at all but received only a rebuke (BT Shabbat 97a).

Miriam’s skin affliction is perceived by the Rabbis as punishment for the sin of slander. Nonetheless, they also describe her many merits as revealed in this episode. They maintain that Miriam intended to praise her brother and to increase procreation; she was punished because of the severity of her act of slander (Sifra, Mezorah 5; Sifrei on Numbers loc. cit.; Avot de-Rabbi Nathan loc. cit.).

According to the Rabbis, Miriam received special treatment when she contracted her skin affliction. The Priests; descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses, who were given the right and obligation to perform the Temple services.kohen was usually entrusted with the purification of individuals so afflicted, but Aaron was invalidated in this case, because he was a relative of Miriam. Consequently, God Himself cared for Miriam’s affliction and functioned as a kohen (Lev. Rabbah 15:8; BT Zevahim 102a). The special attitude to Miriam was also expressed in the entire people’s waiting seven days until she was healed.

In the midrashic expansion, Aaron spoke with Moses and persuaded him to forgive them and to pray for Miriam’s recovery. He reminded him that they were all siblings and had come forth from the same womb (Num. 12:12): “who emerges from his mother’s womb.” Moses did not need Aaron’s plea, and, in any event, wanted to help her (Sifrei on Numbers, 105; Sifrei Zuta 12:12–13). According to another exegetical tradition, Moses drew a circle, stood within it, and declared that he would not budge until Miriam was healed (Avot de-Rabbi Nathan, version A, chap. 9). Moses’s prayer was efficacious to the extent that she did not require an additional isolation period of seven days. A single such period sufficed, even though this was no longer than the confinement required in the case of a daughter punished by a flesh-and-blood father (while this case involved God Himself; see Num. 12:14) (Sifrei on Numbers, 106; Sifrei Zuta 12:14–15).

Moses’s prayer was succinct (Num. 12:13): “O God, pray heal her!” The Rabbis offer different explanations why Moses did not extend his prayer. One reason was lest people say that he prayed at length (more than for other people) only on behalf of his sister. A second reason was that his sister was in distress, and so there was no time for lengthy prayers. A third suggestion is Moses’s fear that people would question the effectiveness of his prayers; in this way, it was clear that his prayer was immediately answered (Sifrei on Numbers, 105). These proposed explanations reflect the outstanding sensitivity required of a leader when he wants to act on behalf of a family member.

Num. 12:16 relates that the people waited for Miriam seven days and only then renewed their journeying. The midrash views this as Miriam’s reward for waiting for Moses at the riverbank (M Sotah 1:9). Another tradition has the Israelites even going back for her three-way stations in their wanderings (Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Masekhta de-Shirah, Beshalah 3). In yet another exegetical retelling, the Israelites initially wanted to continue on their journey, but they encountered various difficulties: the beasts turned around, the cloud did not precede them, the well was no longer with them, nor were Moses and Aaron to be found. They therefore immediately returned to Hazeroth and they understood that all this was on account of Miriam (Midrash Yelamdenu, cited in Yalkut Shimoni, Beha’alotekha, para. 642).

Miriam’s Names

Some of Miriam’s appellations were given her following her skin affliction. In the Rabbinic etymological explanation, the name Miriam reflects the bitterness (mirur) of Israel’s enslavement in Egypt. This fact is used by the author of Seder Olam Rabbah in his calculations of the length of this servitude, which lasted at least as long as Miriam’s age at the time of the Exodus (86), in a calculation that is based on a comparison of her age with those of Moses and Aaron, which are specified in the Torah (Seder Olam Rabbah 3).

The Torah is silent concerning both Miriam’s marriage and her children. According to the aggadic tradition, she was married to Caleb, and thereby entered the family tree of Judah. The names of Caleb’s wives and those of other women who appear in the genealogy of Judah in Chronicles (I Chron. 2:18–20; 4:4–9) were understood by the Rabbis as appellations for Miriam that describe her and her traits.

Some of these names related to her skin affliction: “Azubah” (2:18)—for all forsook her (azvuha) at the beginning; “Jerioth” (idem)—because her face was like curtains (yeri’ot); “[he] had two wives” (4:5)—Miriam became like two wives; “Helah and Naarah” (idem)—she was not both Helah and Naarah, rather, she was first Helah (helah, an invalid) and later, Naarah (na’arah, a young girl) (BT Sotah 11b–12a; Ex. Rabbah 1:17).

Other names teach of Miriam’s beauty: “Ardon” (2:19)—because her face was like a rose (vered); “Zereth” (4:7)—because she became the rival (zarah) of her fellow women; “Zohar” (idem; literally, brilliance)—because her face was [as beautiful] as noon; “Ethnan” (idem)—for whoever saw her took a present (etnan) to his wife (BT Sotah loc. cit.; Ex. Rabbah loc. cit.).

Her other names are “Aharhel” (4:8)—for all the women went out after her (ahareha) at the Song at the Sea; and “Ephrath” (2:19)—because the Israelites were fruitful and multiplied (peru u-rebu) in her time (and perhaps with her help, as well, as a midwife) (Ex. Rabbah loc. cit.).

The name Ephrath is the basis of the Rabbinical connection of Miriam with the Davidic dynasty (i.e., the royal line that she merited), since David is called (I Sam. 17:12): “the son of a certain Ephrathite” (Sifrei on Numbers, 72; BT Sotah loc. cit.; Ex. Rabbah loc. cit.).

The Death of Miriam

A Rabbinic tradition attests that Miriam died on the tenth of Nisan (Seder Olam Rabbah 10; Sifrei on Deuteronomy, 305). The Torah tells of her death in the portion of Hukat (Num. 19:1–22:1); the Rabbis deduce from the juxtaposition of her death and the law of the red heifer that the death of the righteous atones for the sins of Israel: just as the red heifer atones, so, too, did Miriam’s death atone (BT Mo’ed Katan 28a).

For the Rabbis, Miriam’s death is comparable to the death of her brothers. Miriam, like her brothers, died at Mount Nebo (BT Sotah 13b), that is also known as “the heights of Abarim.” The names of the place of their burial denote the fact that these three prophets (nevi’im) did not die because of sin (averah) (Sifrei on Deuteronomy, 338; BT Sotah 13b). In the Rabbinic portrayal, the Angel of Death had no power over Miriam and she died with a kiss by God, which is a death reserved for the righteous (Cant. Rabbah 1:2:5; BT Bava Batra 17a). Miriam was one of the seven over whom worms had no power (Masekhet Derekh Erez 1:17).

Steinmetz, Devora. "A Portrait of Miriam in Rabbinic Midrash." Prooftexts 8, no. 1 (1988): 35-65.