Leading with Timbrels: Another Side to the Passover Story

Every year, my temple holds a women’s seder on the second night of Passover. This ritual has always been important to me because throughout my Jewish education, I have clung to stories as the basis for my learning. At every seder I have ever attended, I have heard the story of the Exodus told in a slightly different way, usually depending on the people present and the particular texts we read. The women’s seder is special because it is the only one that reminds me how Jewish women like me played just as much of a role in the Exodus as their male counterparts. As I began to look for this kind of representation in other parts of Jewish life, I noticed the difficulty of finding female perspectives in much of our sacred text.

As a child, the story of the Exodus from Egypt seemed to be an exception to this rule. After all, I’d grown up hearing about the courageous steps women like Miriam and Yocheved took to protect their family and stand up to injustice. However, as I looked more closely at the text, I discovered that there is more to learn about these better known role models, as well as space in the Exodus narrative for the many traditionally disregarded women who helped deliver the Jewish people from Egypt.

The Exodus would not have happened without women. This is more than my own opinion; it is echoed throughout Midrash and Talmud. Our scholars tell us, “By the merit of righteous women who lived in that generation Israel was redeemed from Egypt.” This statement might seem slightly out of place at first. After all, it’s Moses who is most well- known for leading the Jewish people out of slavery, and helping them to transform from a wandering group of slaves into a unified people. But, several pieces of Midrash point out that without women, the Jewish people might have lost their faith before Moses was even born.

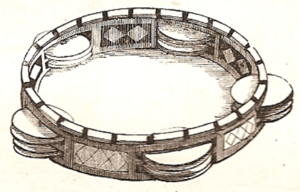

The main virtue attributed to the women of Israel is their optimism. In response to the question of where the women got the flutes and timbrels which they played as they crossed the red sea, Midrash explains that the women had created these instruments ahead of time. In other words, they knew, even in their captivity, that they would someday have cause for celebration. Another even clearer demonstration of faith was the fact that the women continued to have children in slavery, even after Pharaoh decreed that all baby boys would be killed. Many of the men wanted to divorce their wives to avoid the risk of having their children taken from them, but the women refused to give up on the future of their families and their people. By convincing their husbands to continue having children, the women ensured the continued survival of the Jewish people and helped to bring about their hope for a future where their children could be free.

At the women’s seder, we read the poem We All Stood Together by Merle Feld. By taking on the perspective of a Jewish woman at Mount Sinai, Feld explains why women are not represented in our traditional telling of the Exodus. The woman in the poem explains that her brother was able to make himself a part of the narrative by writing down his perspective on the extraordinary things they witnessed and experienced, but she was unable to do so because: “It seems like every time I want to write/I can't/I'm always holding a baby.”

While the women of this generation saved the Jewish people by continuing to raise children, there is a certain irony in the fact that this role also prevented them from inserting their own voices into the record of one of the most vital moments of their own history. In the story of the Exodus, like in many of the central parts of Torah and Jewish tradition, the role of women is no less important than the role of men, but it is minimized. This highlights the fact that women were unable, for various reasons, to record their contributions.

People tend to say that the victors decide history. The only people able to determine how history is ultimately written are those who have the means to pass on their perspectives. Unfortunately, even within groups we see as victors, there are still those whose perspectives are disregarded. Jewish history is full of extraordinary women, but because women have not always had the ability to tell their own stories, they are often excluded. In order to discover our role within the stories that make up so much of our faith, Jewish women must sometimes look deeper within the text than their male counterparts.

There is no doubt in my mind that if we attempt to see from the perspectives of our foremothers as well as our forefathers, we can create a narrative that ultimately teaches us more about our history and our values. The women of the Exodus inspire me to challenge the stories I am told every day, whether they are from Torah or my history textbook. Unfortunately, for these women it is not always enough to shape history; in order to make a lasting impact, we must fight for ownership over the way it is recorded. As I celebrate Passover surrounded by other Jewish women, I attempt to reveal the contributions of the many unnamed women who sang on the shores of the Red Sea, and seek out my own place within Jewish text.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.