Medieval Hebrew Literature: Portrayal of Women

Stereotypes of women, “good” and “bad,” are found throughout the medieval Hebrew canon; With its conventional themes, clichéd metaphors, and stereotyped female figures, medieval Hebrew literature is an unsatisfactory source for tracing the actualities of women’s lives. As against ascetic sentiments that tended to demonize women, a great deal of medieval literature—Hebrew included—is obsessed with the idolization of women, with romantic love and carnal desire, with corporeal beauty and the pleasures of eros.The love poetry cultivated during the Golden Age in Muslim Spain seems to glorify and idealize women, but the female “beloved” is subject to the power of the male “gaze” and male rhetoric.

Poetry Written by Women

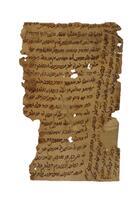

The only medieval Hebrew poem attributed to a female author is a rhymed letter sent by a young wife to her far-away husband. In it she recollects their departure and implores her husband not to forget her and their little child. This poem, dating from the latter part of the tenth century, survived only thanks to the reputation of the author’s more famous husband, the professional poet Dunash ben Labrat (ca. 920– ca. 985), who was the pioneer of Hebrew Golden Age poetry in Muslim Spain (Fleischer, 189–202; Kaufman et al., 62–63). Dunash’s wife is the first identifiable female poet in the Hebrew language since the biblical poets Miriam and Deborah. While Jewish sources do not refer to Qasmuna, Arabic literary historians mention her as a Jewish poet in who wrote in Arabic. They recount that her father (possibly Samuel ha-Nagid [Ibn Naghrela], 993-1056), the eleventh century poet and statesman from Granada) taught her to write verses (Bellamy, 423–424). Other known poets include the noble lady Tolosana de la Cavalleria of Saragossa, who wrote a dirge on the death of her son in the late fourteenth century (Granat, 2013, 152), and Merecina, a rabbi’s wife from mid-fifteenth-century Gerona who composed a single poem, a religious piyyut in which she incorporated an acrostic of her name (Kaufman, 64–65). Our lack of information about other medieval women poets may indicate that they did not exist or that male copyists chose not to preserve their work.

The absence of poetry by Jewish women is striking when compared to the relatively significant number of medieval non-Jewish female poets. In Christian Europe, although outnumbered by men and excluded from the canon, women—troubadours, nuns, mystics, and nobles — did write about their perceptions of life, love, and death in sacred and profane poetry. In recent decades, feminist researchers have rediscovered, reread, and reintegrated these women into the canon, correcting, to an extent, their historical absence (Dinshaw and Wallace, 2003). Even more remarkable are the scores of women who wrote poetry in Arabic. These poets, in both Andalusia and the Middle East, include princesses, courtesans, and slave-girls, as well as fighters, mystics, and musicians; their names, and sometimes also their texts, have been preserved or rediscovered (Nichols, 114–117).

Hebrew Poetry about Women Written by Men

Since the likelihood of discovering more medieval female Jewish poets is dim, a useful approach is to analyze how women and gender are represented in medieval poetry written by men. Historians have attempted to reconstruct women’s actual experiences based on a variety of texts written by men (Grossman; Baskin, 101–108; Assis, 25–59), or from the rare documents where women’s authentic voices can be heard, such as personal letters (Kraemer, 161–182). The task of feminist literary critics is to account for the ideological and symbolic roles designated to women in the male literary imagination, to map the positions of female figures and the positioning of their voices within the patterns of male discourse, and to explore the artistic strategies behind women’s presence/absence in a given text. Feminist criticism asks how literature fictionalizes social practices, and, how, in turn, it reflects its invented fictions back onto the real world (Rosen 1988, 67–88; Rosen 2003).

Stereotypes of women, “good” and “bad,” are found throughout the medieval Hebrew canon (Dishon 2009; Dishon 1994, 35–50; Caballero Navas, 9–16; Huss). The love poetry cultivated during the Golden Age in Muslim Spain (950–1150) seems to glorify and idealize women. Following the themes and style of Arabic poetry, Jewish poets like Samuel ha-Nagid (993–1055), Solomon ibn Gabirol (ca. 1022–ca. 1058/70), Moses ibn Ezra (1060–1139), and Judah Halevi (1075-1141) wrote rhetorically brilliant love poems in Hebrew, positing lofty and dazzling female figures at their center. This idealized lady is exalted but muted, aloof but lethal, tempting but unyielding; she is devoid of personality and speech. Her cruelty and beauty, and the poet’s passion and pain, dominate the poetic descriptions. The poet pleads for her response and her acquiescence in lovemaking. The more the lady remains steadfast in her refusal, the more the poet’s love grows and his pen flows. This male narrative is generated not so much by deep love of the lady as by the poet’s drive to please a male audience that shares his own aesthetic “courtly” values.

While most nineteenth- and twentieth-century mainstream critics have read these poems as manifesting Jewish “hedonism,” “universality,” and “normal sexuality,” a feminist reading reveals an unbalanced power-relationship. The female “beloved” is subject to the power of the male “gaze” and male rhetoric. Although the male speaker describes himself as weak, inferior, and fearful vis-à-vis his lady, the power of language and description is in his hands. Her hair is described as like a bundle of snakes; her eyes shoot arrows; her breasts are like apples growing on a “heart of stone.” She is vampire-like: her nipples are sharp spears threatening to drink the poet’s blood. Her eyes “tear prey like lions, [...] suck and sip my heart’s blood” (Judah Halevi, Diwan 2:6). [All poetry translations are by the author, unless otherwise stated.]

An alternative image to the cruel-but-muted lady in the male love lyric are the passionate voices of singing maidens that appear at the end of Arabic and Hebrew muwashshah poems (Rosen 1985; Rosen 2000, 165–89). These concluding couplets (called kharjas) are often put in the mouths of young women who chant in the colloquial Andalusian-Arabic or in the Romance vernacular. Many scholars believe that these kharjas represent and preserve (or, alternatively, counterfeit) an oral poetic tradition of old songs sung by Iberian women in a Romance dialect. Unlike the aloof lady, these young women play an active role in the love relationship. They daringly suggest secret rendezvous, despite spies and slanderers. They send messengers, consult fortune-tellers, or confess their feelings to mothers and girlfriends. Many of these small songs are complaints about departure and desertion. The women coquettishly offer their bodies to their sweethearts, instructing them in lovemaking, or, bashfully stopping the too bold advances of admirers. Judah Halevi includes the following Romance kharja at the conclusion of a muwashshah: “Don’t touch me, my love;/ I don’t want him who hurts me./ My breast is sensitive./ Stop it, I refuse all [suitors]” (Judah Halevi, Diwan, 2:3).

Another type of woman who appears in Hebrew poetry is the professional musician. The qaynah (as she is called in Arabic) gives concerts at courtly events entertaining an audience of avowed admirers (Rosen 2003, 33-35, Granat). She flirts with them and stirs their emotions: “She parts her scarlet lips, holding the lute like a mother hugging her babe […] / She parts her lips to sing of parting, and as she thrills her voice her tears pour out" (Judah Halevi, Diwan, 1:14).

Another aspect of the beloved woman appears in wedding-songs, a genre reflecting the patriarchal imagination at its most favorable. While the love lyric exalts pre- and extra- marital love with its attractions and perils, the wedding poems depict married love as an Edenic paradise, devoid of danger and sin. The ideal bride is as stunning as the poets’ lady, but not as dangerous. The groom is encouraged (by the poet, or by the bride herself) to ignore the harmless serpents that decorate her face and to enjoy the fruit that grows in her delightful garden/body. The bride yields herself to her groom's pleasure; moreover, she entices the groom with a promise for future harmony and joy: “To you alone I will give my love/And you will lie between my breasts” (Judah Halevi, Diwan 2: 26). The bride is erotic yet pure and obedient, virgin yet a promise of future procreation. In language evoking the biblical Song of Songs, her sexuality is sanctioned by God and men, as eros is integrated within the frame of family and society.

When the bride becomes a wife, eros fades away and woman’s base nature is said to reveal itself fully blown. The wife, especially as she appears in the Hebrew rhymed narratives of the maqama variety (Drory, 190–210; Huss, 1:17–29; Pagis 1976, 199–244), is not mute as is the courtly lady, nor is her voice comely as is the bride’s. The wife’s mouth is ceaselessly open—complaining, lying, rioting, gossiping, revealing secrets, gulping food, and constantly scandalizing her poor husband by demanding money, maids, house utensils, clothes, and jewels:

A devil's shape on a woman’s face is engraved./ When I look at her my body tears apart.

Her speech makes my hair bristle on my head./ Her voice loosens the bonds of my heart.

She closes gates of peace and friendship/ and opens the doors for quarrel and strife.

She builds her house on a mountain of complaints./ Her tent is spread there and stretched tight.

(Joseph ibn Zabara, Schirmann 3:58)

If a wife appears good and obedient it is only because she manages to hide her greed, filth, and treachery; married life becomes the arena for the taming of the shrew. Themes like women’s wiles, female fickleness, and wives’ betrayal are emphasized (Roth, 145–165; Rosen 2003 (chapter 5); Dishon 2009) and husbands are advised to exercise their manly authority since a wife should be disciplined and domesticated. Such is the advice given to husbands by Samuel ha-Nagid in his book of moral epigrams: “Beat your wife daily, lest she rules over/ you like a man, and raises her head up./ Be not, my son, your wife’s wife,/ and let her not be her husband’s husband” (Ben Mishle, 162). Wifehood is the result of a process of culturing and disciplining. Hence, women should be contained within walls, veiled, hidden, and muted: “Walls and castles were erected for woman/—her glory lies in bedspreads and spinning. / Her face is a pudendum displayed on the main road/ that has to be covered by shawls and veils.” (ibid., 283).

In marriage the wife is required to repress her feelings, opinions, appetites, desires, likes, and dislikes. She will earn the title of “the princess of the house” only if she agrees to be her husband’s servile maid. Mothers, no less than fathers and husbands, were agents of the patriarchal construction of wifehood. The following voice is that of a mother: “Beware of whatever makes your husband angry. Do not express your own anger. . . . Speak softly to him to abate his anger. Cook for him whatever he desires, and pretend to like his favorite dishes even if you don’t. . . . Save his money. . . . Don’t be jealous. . .” etc. (from Isaac, Mishle Arav, in Dishon 1986, 4).

The patriarchal imagination identified woman with nature and its uncontrollable forces. This is what a duped groom relates of what he saw when he uncovered his bride’s face:

Her face—fury, her voice—thunder […], her mouth like a she-donkey’s, her breath—putrid. Her dried up cheeks—as if Satan himself had painted them with coal […]. Her eyes—scorpions, her stature—a town wall, her thighs—two tree-trunks […]. Her image resembles the angels of death. […]. Her mouth—a grave for food and drinks, her belly—a cave, her teeth putrid like bears’, full of slime and excrement. Her speech—like turmoil at midnight, her breath like a whirlwind. Her teeth grind food like a pestle and mortar before it all falls into her deep abyss. (from the 6th maqama by Judah al-Harizi, Schirmann 3: 120-122).

The female body, portrayed as grotesque, is dismembered and fragmented, with each limb hyperbolically compared to another terrifying object. The result is a disproportionate, surrealistic, mythical, horrifying creature. The emphasis on the mouth, lips, and teeth, and on what comes out of it (spittle, breath, and a horrible voice) is noteworthy: her mouth, analogous to her insatiable vagina, is busy grinding and gulping.

Another appalling female representation is that of Tevel as it appears in dirges over the dead and in ascetic (penitential) poems. Tevel (earth, or the terrestrial world) is the allegorical personification of the world’s evil. The belief that women are not only its embodiment but its very cause goes hand in hand with the perception that the material corrupted world itself is essentially feminine. The material world and its temptations are imagined as a female whose outwardly attractive appearance hides her true being as an ugly crone, a rotten prostitute. Wicked Tevel is said to hypnotize her human victims with her beauty, her riches, her scarlet skirts, gold, jewels, wine, nectar, fruits, and so on. She promises men (who are her, in fact, her progeny) possessions, honor, and stature but is then unfaithful to them, revealing her horrible nature. She marries her children and then divorces them; makes love and slays her lovers. Men should resist her dark attraction:

She lures the boors with her riches; / she tempts them with fine silks,

Then she upsets them with much grief and pain— / and so few are the drops of her cure!

(Moses ibn Ezra 1:86)

Tevel seems to conform to the Jungian-Neumannian archetypes of the Great Adulteress and the Terrible Mother. She is the cannibal mother of her sons, who are also her philanderers. Her womb is their tomb. She feeds her children and then feeds on them: “She devours her children—though they have hardly savored her bread and flesh” (Solomon ibn Gabirol, 305). As Mother she should be dishonored and her shame made known. Her sons “ought to strip off the rims of your coat over your face” (Moshe ibn Ezra, 151).

Women’s exemplary virtues are listed in dirges. A deceased woman is praised as her husband’s support and as a mother dedicated to her children; she is lauded for her piety, acumen, kindness, nobility, philanthropy, diligence, and industry. A handful of Andalusian odes (in the literary form of the qasida) lament the deaths of the wives or daughters of famous rabbis or comrade-poets. A group of dirges in a popular variety of strophic poetry by Judah Halevi diverges from this typical mold in realistic reflections of actual situations. These include a mother lamenting her young daughter who died just before her wedding. Hundreds of such dirges (mostly anonymous) have been found in the Cairo Genizah (Beeri). The male mourners (especially husbands, but also other male relatives) reveal their agitated emotions and express the pain and loss of the family and community. A number of them declare that the deceased woman was literate, educated, versed in the Torah, and in some cases, a teacher of young children.

Liturgical poetry features the allegorical representation of the feminine Knesset Israel (the synagogue of Israel). Her speech is laden with the communal emotions of the nation (Scheindlin 1991). Following the traditions of prophetic and A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrashic allegory, Knesset Israel was, in the biblical past, the passionate paramour of Israel’s God, but now she is forsaken, exiled, and despised, politically oppressed, and socially inferior. Her speech is that of a divorcée (or worse, a wife abandoned without divorce), a disenfranchised noblewoman, a bereaved mother, a disgraced widow, a sinful wife, a stray daughter, an outcast, who longs to be reunited with her husband, her children, and her homeland. Read as a political discourse, medieval Hebrew liturgy is the expression of a powerless minority. The choice of a woman to represent the praying congregation (and the national community, as a whole), as well as the choice of a woman’s voice to address God, is quite intriguing since Jewish women did not participate in public prayer, and, moreover, a woman’s voice in a communal setting was considered “an obscenity.”

Many liturgical pieces have as their theme the human soul (nefesh), which is gendered as feminine in Hebrew. In an allegorical extension, the grammatically feminine becomes figuratively female. The soul is the speaking subject (or the addressee) in many liturgical-penitential poems. The soul’s tragedy is her union with the body, and her attraction to it. Her pollution, caused by the sinful nature of the female body and its functions, especially menstruation, divorces her from the intellect and God. The female soul is called upon to purify herself, to rid herself from her femaleness, so that she may reconnect herself with the elevated male elements. In liturgical poetry and moral allegories, the soul speaks as a beloved gazelle yearning for union with her lover; as a deserted plaintive wife enslaved to her enemy, the body; as estranged daughter entreating her father God to be permitted to return home; or as a pupil listening to the lectures of the (platonic) Intellect. At times she is the intellectual soul, preaching to the stubborn body (Scheindlin 1991; Tanenbaum; Rosen 2003).

Poetry too appears as an allegorized figure. Gendered feminine, she is called shirah (poetry; poem), or bat ha-shir (literally, “poetry's daughter”). Like a woman, poetry is required to be beautiful and elegantly clad (that is, with rhetorical ornaments). She is depicted as a bride, adorned, veiled, and perfumed, or else, as an enchantress, rousing the poet’s poetic libido: “She hunts her lover’s heart without a hook/but with the sweetness of her mouth.” Poetry is, at one and the same time, the poet’s daughter, his mother, and his lustful mistress. These sexual, rather incestuous, metaphors highlight the link between eros and poetic creativity. The ungainly poem, which does not meet the required aesthetic standards, is likened to a menstruating woman. Poetry resembles woman not only in beauty but also in its use of artifice and deceit. The statement, “The best of poetry is in its lies,” indicates that poetry’s use of figurative rather than literal language is a form of deception. The mendacity of poetry, gendered feminine, is opposed to male philosophic truth. Thus, Moses Maimonides (1138-1204) links poetry with the feminine aspect in the male psyche and criticizes listening to the singing of women, since singing and poetry stir sexual emotions in men. Indeed, a growing animosity toward poetry in thirteenth-century Europe coincides with the flourishing of misogynistic literature (Rosen 2003).

The inferiority of women based on metaphysical, biological, or ascetic grounds was a constant theme for medieval Jewish philosophers, doctors, and moralists. They identified women with matter, body, and defiled sexuality. Men were repeatedly warned against women’s threat to their well-being and were urged to exclude women and silence them. Women were relegated to the realm of the beastly, the evil, and the demonic and were banished from the sphere of the intellect and the divine. They were considered an obstacle to a man’s peace in this world, and to his redemption in the hereafter.

The Hebrew maqama literature that flourished from the early thirteenth century on was infected by misogynous and misogamous (marriage–hating) humor. Minhat Yehuda Sone ha-Nashim [The Offering of Judah the Women-Hater] was written by Judah ibn Shabbetai around 1208 (Ibn Shabbetai; excepts in Schirmann 3:67-86; Rosen 2003, chapter 5). Its protagonist, Zerah, persuades husbands to divorce their wives and dissuades young men from marriage. Women, young and old, convene to struggle against his message and to save the institution of marriage. They insist on a wife’s right to be sexually satisfied (and on her husband’s religious duty [‘onah] to do so). Led by an shrewish old woman, they tempt Zerah to marry a flawless virgin (who is to be replaced later by an ugly, wicked, greedy, and big-mouthed woman). Upon unveiling her, Zerah reveals his wife’s true face and sues for divorce. The judge finds Zerah guilty of undermining marriage and sentences him to death. At this point, Judah, the author, comes to the rescue of his fictional protagonist, declaring that Zerah is an imaginary creature, which he, Judah himself, had invented. This complex ending dramatizes the cultural ambivalence vis-à-vis marriage in Iberian Jewish culture. This hostility, which co-existed among the intellectual elite with the positive Jewish values of marriage and procreation, could have permeated Jewish circles through ascetic trends in medieval Islam and Christianity (Biale).

“The Offering of Judah the Women-Hater” started a literary polemic that lasted throughout the thirteenth century. An immediate response was Ezrat Nashim [In defence of women] (Schirmann, 3: 87-96), whose title carries the double meaning of a woman’s support of her husband and the poet as defender of women. Its Provençal author, Isaac, admits that he was encouraged to write his story by those women abused by Ibn Shabbetai. In it, Rachel, a young pretty wife, an ideal helpmate, loyal and efficacious, helps her husband with her acumen and delivers him from great troubles (Schirmann, 3: 88–96). Another Provencal author, Yeda’aya ha-Penini (ca. 1270 -ca. 1340), responded to Ibn Shabbetai’s hostile work with his Ohev Nashim [A Lover of Women]; 1295] (Schirmann, 4: 489-496). Here, women, led by a virtuous heroine, celebrate their victory over marriage-haters such as Zerah and Ibn Shabbetai. When Ibn Shabbetai descends from heaven to defend his work in court, the court harshly denounces his anti-marriage views. Although the judges’ appreciation for his literary work saves him from a death verdict, the court rules unambiguously that marriage is mandatory and that monogamy is obligatory.

One should not be deluded by these “defenses of women.” What is defended here is primarily marriage and not women. Marriage is good while woman is basically evil. When women (like Rachel in Ohav Nashim) are dubbed “good,” it is only because they are devoted to their husbands. This “profeminine discourse [has an] unfeminist quality” (Blamires, 12) and springs from the heart of patriarchy. Such works are clearly projections onto women (and marriage) of men’s concerns and anxieties.

Debates about Women in Italian Hebrew Literature

Debates for and against women are also a theme in Hebrew literature in Italy. The Mahbarot, a collection of poetry by Immanuel of Rome (1261-1328), is full of male poets entertaining themselves with the rhetorical sport of “praising the beautiful woman” and “condemning the ugly,” using highly sophisticated language (Immanuel of Rome, 35–43). Throughout the sixteenth century, some dozen Italian-Hebrew poets were involved in debates over women, cast in various poetic forms and influenced by Italian literature (Pagis 1986, 259–300). The Hebrew poets brought arguments from the Hebrew Bible, Greek mythology, and Roman history. Although no female writers participated in these poetic polemics, women were active readers and patrons.

Underlying many of the discourses and genres of medieval Hebrew literature is a framework of a male conversation in which men convene at the city gates or in literary salons to share poems, stories, sermons, epigrams, and jokes. The intention of such “homo-textual” economy is to share textual pleasure, particularly on the topic of “woman.” In the sixteenth and seventeenth maqama by Immanuel of Rome, a poetic contest is held between a husband and two suitors of his pretty wife. The three rivals agree that the winner’s prize will be the wife’s body. This pretty lady’s husband is impotent, and she, still a virgin, is eager to experience sex. Hence, she encourages her suitors to win the contest. She appears to play an active role in this comedy but actually serves as a medium channeling male rhetorical energy. What starts as a hilarious burlesque with an exchange of witty epigrams and bawdy rhymes, ends with the husband’s victory. The impotent husband wins back his own wife, who is paradoxically both a virgin and an adulterer, a wife whom he will never be able to satisfy. Marriage, however destitute and absurd, prevails (Rosen 2003, chapter 6).

In Immanuel’s second Mahberet, the poet falls in love with his patron’s beautiful half-sister, who is very religious and inaccessible to men. Immanuel conducts a long correspondence with her, in which she shows no lesser rhetorical talent than he. The more she resists, the more Immanuel’s lust—as well as his poetic stimulus—is ignited. The refusing lady succumbs at last and is ready for love-making. The poet is foolish enough to boast about it to his patron, who firmly disapproves of the romance. Immanuel apologizes to the lady, admitting that all his praises of her were only intended to put her chastity to test. Realizing that she has been a pawn in men’s rhetorical games, the lady is overcome by melancholy and disgrace and starves herself to death. (Rosen 2003, chapter 6).

Conclusion

The ambivalence towards women that was widespread in medieval Muslim and Christian societies found its literary counterpart in a poetics of women’s adoration and condemnation. As against ascetic sentiments that tended to demonize women, a great deal of medieval literature—Hebrew included—is obsessed with the idolization of women, with romantic love and carnal desire, with corporeal beauty and the pleasures of eros. Writing about ambivalent attitudes in medieval Jewish-Spanish culture concerning sexuality, women, and marriage, David Biale has stated, “Indeed two souls often beat within the breast of the elite itself, and sometimes within the breast of the same individual. On the one hand, Jewish culture shared with its surroundings an extraordinary openness to the erotic. . . On the other hand, Jewish philosophers [adopted a] … negative stance on sexuality and the body. … Ambivalence over erotic behavior therefore plagued the Jewish elite” (Biale 1992, 89).

The issue of humor is also closely connected to the homo-textual frame. The humor employed “between men” is unavoidably gendered: Jokes not to be told in mixed company are spoken; men laugh at the expense of an absent woman; grotesque descriptions of women pass as entertainment. Most critical treatments of such elements in these works read them as parodies and satires; even modern male critics have seen the ridicule of woman as a legitimate pastime. That this humor was gendered has gone without notice; on the contrary, the “humoristic intention” of the authors was said to dissolve, or undercut, misogyny. However, as feminist criticism has demonstrated, “humor” is not the opposite of misogyny but rather one of its most effective tools.

With its conventional themes, clichéd metaphors, and stereotyped female figures, medieval Hebrew literature is an unsatisfactory source for tracing the actualities of women’s lives. Rather than supplying evidence of their presence and experiences, this literature, like contemporaneous literatures in other languages, more often furnished manifestations of their absence and erasure. This elimination of “real” women was accomplished by means of muting and silencing female figures; by stereotyping, allegorization, abstraction (woman as concept), by mythologization and dehumanizing (nymph, medusa, amazon, she-demon etc.), and by objectification (woman is matter, commodity, chattel, or body without subjectivity or mind), among other tropes. It is the task of feminist literary criticism to identify and deconstruct these deliberate misrepresentations.

Closely related to the question of women’s presence/absence is the issue of female voices. To what extent are female voices, captured within male texts, “authentic” and unmediated? Aren’t they muffled by male transmission? Don’t they serve the author’s androcentric position? Female voices often seem to embody patriarchal “truths” about women’s speech (women abuse language by lying, quarreling, complaining, enticing, and so on). However, utterances by female protagonists may help to reveal the limits of the misogynistic logic that produced them. They indicate points from which the homo-textual monolith can be dismantled. A woman’s voice, clear and assertive, is heard in al-Harizi’s forty-first maqama that is fashioned as a debate between a man and a woman on the issue of women’s worth. Here, the woman objects to the objectification of her gender and their silencing. She refutes one by one men’s assumptions about women’s inferiority. She acts as a capable advocate of womankind, manifesting familiarity with male erudition (Bible, Talmud, Aristotle, Maimonides). Her resisting speech, inserted within the dominant male discourse, foreshadows the “resisting reader” of modern feminist criticism. As such it invites reading these female utterances as sites of embedded empowerment and resistance; they are seeds of “otherness” which defy the self-proclaimed and ostensibly solid assumptions of their male creators (Rosen 2003, chapter 6).

Primary sources

Al-Harizi, Judah. “Sefer Tahkemoni” (selection). In Hebrew Poetry in Spain and Provence [Hebrew], edited by Jefim (Hayyim) Schirmann, 115–123. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: 1960,.

Ibn Ezra, Moses. Secular Poems, edited by Hayyim Brody. Berlin: 1935.

Halevi, Judah. In Diwan Jehuda ha-Levi, edited by Heinrich Brody. Berlin: 1894–1930.

Ha-Nagid, Shmuel. “Ben Mishle.” In Divan Shmuel Hanagid, vol. 2, edited by Dov Jarden. Jerusalem: 1982.

Ibn Gabirol, Solomon. Secular Poems, edited by Hayyim Brody and Hayyim Schirmann. Jerusalem: 1976.

Ibn Shabbetai, Yehudah. Critical Editions of “Minhat Yehudah,” “Ezrat ha-Nashim” and “Ein Mishpat” with Prefaces, Variants, Sources and Annotations [Hebrew], edited by Matti Huss. Jerusalem: 1991.

Ibn Zabara, Joseph. “Sefer Sha’ashu’im.” In Hebrew Poetry in Spain and Provence [Hebrew], edited by Jefim (Hayyim) Schirmann. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: 1960.

Immanuel of Rome. Mahberot Immanuel Ha-Romi, edited by Dov Jarden. Jerusalem: 1957.

Secondary sources

Assis, Yom Tov. “Sexual Behaviour in Medieval Hispano-Jewish Society.” In Jewish History: Essays in Honour of Chimen Abramsky, edited by Ada Rapoport-Albert and Steven J. Zipperstein, 25–59. London: P. Halban,1988.

Baskin, Judith R., “Jewish Women in the Middle Ages.” In Jewish Women in Historical Perspective. 2nd Edition, edited by Judith R. Baskin, 101–127. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998.

Beeri, Tova. “Dirges for Unusual Female Figures” [Hebrew]. In Ot Letova: Essays in Honor of Professor Tova Rosen, edited by Eli Yassif et al. Mikan 2 (2012): 98-114.

Bellamy, James A. “Qasmūna the Poetess: Who Was She?” Journal of the American Oriental Society 103 (1983): 423–424.

Biale, David. Eros and the Jews: From Biblical Israel to Contemporary America. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Blamires, Alcuin. The Case for Women in Medieval Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Caballero Navas, Carmen. “Women Images and Motifs in Hebrew Andalusian Poetry.” World Congress of Jewish Studies 11, C3 (1994): 9–16.

Dinshaw, Carolyn and David Wallace, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women’s Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Dishon, Judith. “Images of Women in Medieval Hebrew Literature.” In Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing, edited by Judith R. Baskin, 35–50. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994.

Dishon, Judith. Good Woman Bad Woman: Loyal Wise Women and Unfaithful Treacherous Women in Medieval Hebrew Stories [Hebrew]. Jerusalem: 2009.

Drory, Rina. “The Maqāma.” In The Literature of Al-Andalus, edited by María Rosa Menocal, Raymond P. Scheindlin, and Michael Sells, 190–210. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Fleischer, Ezra. “On Dunash Ben Labrat, His Wife and His Son: New Light on the Beginnings of the Hebrew-Spanish School” [Hebrew]. Jerusalem Studies in Hebrew Literature 5 (1984): 189–202.

Granat, Yehoshua. "'Unto the Voice of the Girl's Songs': On Singing Women in Medieval Hebrew Poetry (The Andalusian School and its Offshoots)" [Hebrew]. In Textures: Culture, Literature, Folklore, for Galit Hasan-Rokem, edited by Avigdoor Shin'an and Hagar Salmon. Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Folklore, 28 (2013): 153–168.

Grossman, Avraham. Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Europe in the Middle Ages [Hebrew]. Jerusalem: 2001; English translation by Jonathan Chipman, Waltham MA: Brandeis University Press, 2004.

Harris, Julie A. “Finding a place for women's creativity in medieval Iberia and modern scholarship.” In Women’s Creativity and the Three Faiths of Iberia: Reassessing the Roles of Women as ‘Makers’ of Medieval Art and Architecture. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 6 (2014): 1–14.

Huss, Matti. “Misogyny in the Andalusian School of Poetry” [Hebrew]. In Studies in Hebrew Literature of the Middle Ages and Renaissance in Honor of Professor Yonah Davi, edited by Tova Rosen and Avner Holtzman. Te’uda 19 (2012): 29–53.

Kaufman, Shirley, Galit Hasan-Rokem and Tamar S. Hess, eds. New York: The Feminist Press, 1999.

Kraemer, Joel L. “Women’s Letters from the Cairo Geniza” [Hebrew]. In A View into the Lives of Women in Jewish Societies, edited by Yael Azmon, 161–182. Jerusalem: 1995.

Nichols, J.M. “Arabic Women Poets in Al-Andalus.” Maghrib Review 4 (1979): 114–117.

Pagis, Dan. Change and Tradition in Secular Poetry: Spain and Italy [Hebrew]. Jerusalem: 1976.

Pagis, Dan. “The Controversy Concerning the Female Image in Hebrew Poetry in Italy” [Hebrew]. Jerusalem Studies in Hebrew Literature 9 (1986): 259–300.

Rosen, Tova. “On Tongues Being Bound and Let Loose: Women in Medieval Hebrew Literature.” Prooftexts 8 (1988): 67–88.

Rosen, Tova. The Hebrew Girdle Poem (Muwashshah) in the Middle Ages [Hebrew]. Haifa: 1985.

Rosen, Tova. “The Muwashshah.” In The Literature of Al-Andalus, edited by María Rosa Menocal, Raymond P. Scheindlin, and Michael Sells, 165–189. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Rosen, Tova. Unveiling Eve: Reading Gender in Medieval Hebrew Literature. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Roth, Norman. “The ‘Wiles of Women’ Motif in the Medieval Hebrew Literature of Spain.” Hebrew Annual Review 2 (1978): 145–165.

Scheindlin, Raymond P. Wine, Women and Death: Medieval Hebrew Poems on the Good Life. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society,1986.

Scheindlin, Raymond P. The Gazelle: Medieval Hebrew Poems on God, Israel and the Soul. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1991.

Schirmann, Jefim (Hayyim), ed. Hebrew Poetry in Spain and Provence [Hebrew]. Four volumes. Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: 1960.

Szpiech, Ryan. “Critical cluster: between gender and genre in later-medieval Sepharad: love, sex, and polemics in Hebrew writing from Christian Iberia.” Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 3 (2011): 119–129.